Design trends have increasingly favored collaboration in workspaces over the last decade. Given that “poor acoustics” is the number one cause of dissatisfaction and focus work is the primary objective of those using offices, it is clearly time to prioritize occupants’ need for quiet and privacy. Fortunately, spaces designed to facilitate concentration have also proven to be more conducive to collaboration than those primarily designed for only collaboration.

Of course, offering adjunct spaces where employees can join their colleagues for face-to-face time is also important. Considering 72 percent of adults report feeling lonely—and hyposensitive neurodiverse individuals require more, rather than less, sensory stimulation to focus and feel safe in social engagement—communal areas that help build relationships and offer more “energetic” acoustics also support mental health and wellbeing.10 Organizations can also offer additional aural experiences such as relaxation rooms that employ natural sounds to stimulate the parasympathetic nervous system (i.e. a “rest and digest” state). Providing a variety of spaces with different auditory features from which to select has the added benefit of increasing occupants’ feelings of control over their work environment.10

That said, self-awareness is likely insufficient to achieve occupant-centric goals because there are aspects of the environment that occupants may not consciously recognize or fully appreciate as being either beneficial or detrimental to health and wellbeing. At the same time, these aspects are not adequately accounted for in current noise-rating systems or even in recently developed building standards geared toward wellbeing.

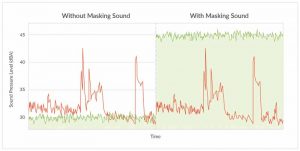

Indeed, most employees’ understanding of acoustics primarily stems from noise exposure theory and its focus on level or, more colloquially, “loudness.”11 Hence, the answer to the question “What constitutes ‘good acoustics’ within the workplace?” is often simply “an environment with little to no noise.” Given this viewpoint, the notion of intentionally increasing ambient sound levels to achieve a quieter environment—or, rather, one occupants will perceive as quiet—may seem counterintuitive, but, contrary to popular understanding, a person’s perceptions of sound have less to do with the lowest level of sound humans they can hear, and more to do with their ability to identify and discern sounds within their acoustic environment.

Sound versus noise

To move acoustic design forward, one must first address what is perhaps the most pervasive source of confusion in architectural acoustics: misuse of the terms “sound” and “noise.”12

Although these words are often used interchangeably—as are “ambient sound” and “ambient noise”—“sound” refers to acoustic waves (or, in the case of occupants, the transportation of physical vibrations in the air within the human ear’s frequency range of 20 to 20,000 Hz), while “noise” is essentially “unwanted and/or harmful sound” or, in Kryter’s words, “audible acoustic energy…that is unwanted because it has adverse auditory and nonauditory physiological or psychological effects on people.”13

The classification of some types of sounds as “unwanted” is key to achieving “good acoustics.” Many studies into non-auditory health effects consider noise emitted by industrial and environmental sources, as well as transportation (e.g. road, rail, and airplane traffic); however, in spaces with higher occupant densities such as offices, occupant-generated noise is the most significant cause of acoustical dissatisfaction. Traditional assessment methods seldom make provisions for this source (focusing on building-related systems, services, and utilities) and, because of its complex nature, building professionals are not easily able to account for it during design—that is, unless they put sound to work.