Exploring how sound and noise impact wellbeing in office design

Sound is continuously produced and present in the built and natural environment—by individuals and those around them, office equipment, and essential building systems, services, and utilities that support other environmental parameters within the space—and it also enters from the outdoors. This understanding—that everyone is constantly surrounded by acoustic energy—helps in exploring more nuanced acoustical concepts, such as the “audibility” of sound and its beneficial uses (i.e. how it can be leveraged to support occupant needs), and not only the adverse effects of noise.

The Masking Effect

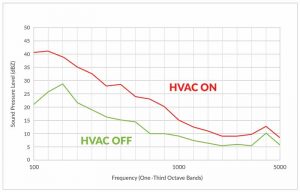

As an example, imagine a room that has sufficient insulation to prevent noise transmission, allowing one to solely focus on the interior ambient conditions. Occupancy is limited to one person. The resulting space is one in which the overall background sound level is exceptionally low. Now imagine what this space may or may not sound like. Most would describe it as “silent.” In practice, environments designed to meet this extreme criterion are highly specialized acoustical facilities, such as anechoic chambers, and occupants often describe their experience as uncomfortable, unsettling, or even intolerable for reasons that include being able to hear their own heartbeats and other bodily functions, given the lack of “interfering” sound. Similarly, ambient “silence” (in this case, low or intermittently low background sound levels) in an office makes surrounding conversations and acoustical disturbances easier to hear.

Other sounds present within a space, particularly its ambient acoustic conditions, such as background sound (or lack of it), affect the perception of sounds in that space. The physics behind this effect was documented as early as the 1950s and referred to as the Masking Effect. To be clear, it does not explain human acceptance or assessment of sounds, only the ability to hear, identify, and differentiate between them. It is an effect routinely experienced in everyday life due to things such as blowing wind, running water, a murmuring crowd, and HVAC, but rarely thought about in the context of the built environment. That said, the only time such ambient sound typically falls below the threshold of hearing is when special effort is made to reduce it, as in an anechoic chamber or recording studio. Since background sound is present in just about every inhabited environment, in addition to making people more vulnerable to acoustical disturbances, its absence can also feel “unnatural.”

As interest lies in conditions conducive to acoustical comfort rather than discomfort, the reader is now invited to add a level of background sound to the imaginary room, such as that produced by HVAC. Technically, this sound corresponds with the typical maximum limits (30 to 55 dBA) defined in the ASHRAE Handbook – HVAC Applications. Since frequency plays a role in determining comfort, with low, mid, or high frequencies potentially causing discomfort due to their rumbling, buzzing, or hissing content, the reader should also apply an appropriate spectrum—a concept at the heart of most noise-rating systems, which depend on a reference contour to assess whether the ambient acoustic conditions are spectrally “neutral.”

However, because building-related systems, services, and utilities are designed to support other functional needs (e.g. thermal, air quality, water, lighting) and sound is simply a byproduct, it varies (temporally) according to the optimal performance and efficiency conditions of the various components. At the same time, the positioning and arrangement of these sources, which encompass elements such as ductwork and piping, exert a significant influence on how acoustic energy is distributed within a facility, particularly in terms of its spatial transmission. In other words, in practice, the background sound (or noise) produced by such equipment is not temporally or spatially consistent, or spectrally neutral.14 Building design professionals can only strive to ensure overall levels do not exceed acceptable maximum limits.