Although acoustical comfort is a relatable concept, many consider it more subjective than objective. By quantifying the degree to which humans can perceive sound—and, in the case of masking technology, conforming to a preferred spectrum—the Masking Effect demonstrates why this belief is misinformed. Similarly, the argument for acoustical privacy is often perceived as niche and only relevant to occupants of certain spaces (e.g. in medical exam rooms), even though the conditions required to achieve it are the same as those needed for focus (e.g. in open plan offices).

In the end, sound is all around and the physics relating the Masking Effect are omnipresent conditions. Building design professionals can intentionally shape those conditions using the type of noninformational broadband sound that forms the backdrop of occupants’ daily lives, but optimized for productivity, health, wellbeing, and satisfaction.

Notes

1 Refer to T. Sheridan and K. Van Lengen, “Hearing Architecture: Exploring and designing the aural environment,” Journal of Architectural Education, November 2003.

2 The decibel (dB) is typically used to express the “loudness” of sound. The scale is logarithmic, so although the numerical difference between two levels might appear small, the actual difference is exponential. For example, the energy of an 80 dB sound is 1,585 times greater than one of 48 dB. Expressed in terms of distance, if 80 dB is equivalent to 1.6 km (1 miles), 48 dB is only 1 m (3 ft).

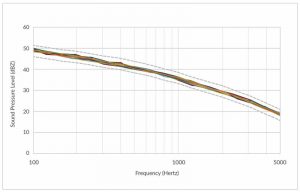

3 The A-weighted level (dBA) provides better indication of occupants’ impression of sounds than the decibel (dB) because it applies a set of “corrections” to instrument-measured sound levels that account for our sensitivity to different frequencies. For example, if two tones (e.g. 200 Hz and 1,000 Hz) differ in non-weighted level (e.g. 60.85 dB and 50 dB, respectively), people may still perceive them as having equal “loudness” (e.g. 50 dBA) because humans are less sensitive to lower-frequency sounds than high ones.

4 Refer to B. Brown, P. Rutherford and P. Crawford, “The role of noise in clinical environments with particular reference to mental health care: A narrative review,” International Journal of Nursing Studies, vol. 52, no. 9, 2015.

5 See V. Drummer, A. Taylor and S. Basque, “Designing for Neurodiversity: Creating spaces that are inclusive of all,” www.stantec.com/en/ideas/topic/buildings/designing-for-neurodiversity-creating-spaces-inclusive-of-all, 2013.

6 To help prevent hearing loss related to use of a personal audio system (PAS) such as a mobile phone and headset, one should follow the recommendations outlined in ITU-T H.870 (03/2022), Guidelines for safe listening devices/systems. It is also important to note that noise-cancelling headphones block speech and background noise equally, meaning the relative difference between them remains the same; they do not reduce speech intelligibility.

7 Refer to T. Parkinson, S. Schiavon, J. Kim, and G. Betti, “Common sources of occupant dissatisfaction with workspace environments in 600 office buildings,” Buildings and Cities, 4(1), 2023.

8 See note 5.

9 Refer to the Gensler Research Institute, “Returning to the Office” briefing based on data captured by Gensler’s U.S. Workplace Survey 2022.

10 To avoid interruption from external sources, the intentional introduction of aural experiences in spaces requires careful control of their boundaries and the acoustic conditions within them.

11 Level is a single-value metric arrived via the sum of its frequency components, measured over time. Its simplicity—in terms of both measurement and as a concept—is one reason why it is commonly used by those in the building industry (e.g. owners, architects, designers, engineers), but there are nuances to this parameter that often cause confusion (e.g. as sound is measured over time, a constant sound and an intermittent sound measured over a certain sampling period may be equal in level) and the numeric value offers little insight into the characteristics of a noise, only its relative “loudness.” Sounds can also vary in spectrum (e.g. rumbly, buzzy, hissy), temporal characteristics (e.g. constant, fluctuating, surging, intermittent), as well as spatially (e.g. overhead, adjacent, throughout a space).

12 For more on this topic, see “Rethinking Acoustics: Understanding silence and quiet in the built environment” by V. Koukounian and N. Moeller in the August 2020 issue of The Construction Specifier.

13 Refer to D. Fink, “A New Definition of Noise: Noise is unwanted and/or harmful sound. Noise is the new ‘second hand smoke,” Acoustical Society of America’s Proceedings of Meetings on Acoustics, January 2019.

14 Similarly, music and nature sounds cannot be relied upon to mask noise and speech adequately or consistently. It is also important to note that they are also subject to personal preference, and occupants’ response to nature sounds (e.g. running water) can be further affected by lack of associated visual stimulus (e.g. a waterfall). Where appropriate (e.g. in lobbies and relaxation rooms), these sounds can be used in conjunction with masking; the latter establishes the foundation for speech privacy and noise control, while the former achieves other auditory goals.

15 For more on this topic, see “In Pursuit of Acoustical Equity: Controlling temporal, spectral, and spatial properties of sound” by V. Koukounian and N. Moeller in the May 2021 issue of The Construction Specifier.

Authors

Niklas Moeller is the vice-president of K.R. Moeller Associates Ltd., manufacturer of the LogiSon Acoustic Network and MODIO Guestroom Acoustic Control. He has more than 25 years’ experience in the sound-masking industry. Moeller can be reached via email at nmoeller@logison.com.

Niklas Moeller is the vice-president of K.R. Moeller Associates Ltd., manufacturer of the LogiSon Acoustic Network and MODIO Guestroom Acoustic Control. He has more than 25 years’ experience in the sound-masking industry. Moeller can be reached via email at nmoeller@logison.com.

Viken Koukounian, PhD, P.Eng., is director of engineering at Parklane. He is an active and participating member of many international standardization organizations, such as the Acoustical Society of America (ASA), ASHRAE, ASTM, the Green Building Initiative (GBI), and the International WELL Building Institute (IWBI), the Standards Council of Canada (SCC), and also represents Canada at International Organization of Standardization (ISO) meetings. He completed his doctorate at Queen’s University (Kingston, Ontario, Canada) with foci in experimental and computational acoustics and vibration. Koukounian can be reached via email at viken@parklanemechanical.com.

Viken Koukounian, PhD, P.Eng., is director of engineering at Parklane. He is an active and participating member of many international standardization organizations, such as the Acoustical Society of America (ASA), ASHRAE, ASTM, the Green Building Initiative (GBI), and the International WELL Building Institute (IWBI), the Standards Council of Canada (SCC), and also represents Canada at International Organization of Standardization (ISO) meetings. He completed his doctorate at Queen’s University (Kingston, Ontario, Canada) with foci in experimental and computational acoustics and vibration. Koukounian can be reached via email at viken@parklanemechanical.com.