Exploring how sound and noise impact wellbeing in office design

by arslan_ahmed | December 8, 2023 4:00 pm

[1]

[1]By Niklas Moeller and Viken Koukounian, PhD, P.Eng.

While sight is generally prioritized over other sensory modalities during building design, a completed structure’s aural qualities do not simply provide a neutral backdrop for activities—a fact apparent to those who managed to carve out “quieter” home offices during the pandemic, only to be called back to noisy, overstimulating commercial and public spaces.

During the intervening pandemic period, many employees also began paying greater attention to their personal wellbeing, intensifying expectations for healthy workspaces. Although the workplace category remains the slowest growing within a projected USD $7 million world wellness market by 2025, the Global Wellness Institute (GWI) attributes this lag to the shift organizations are finally making from compartmentalized wellness programs aimed at treating symptoms—such as stress, disengagement, and absenteeism—to more holistic and proactive approaches that tackle problems at their source by, for example, leveraging workplace design.

To tap into the built environment’s full potential to improve wellbeing, one needs to better understand not only how noise negatively affects occupants’ physical and mental health, but the ways in which “the sonic aspect of buildings can be intentionally articulated to achieve a richer, more satisfying built environment: one that responds to the ear as well as the eye.”1

Auditory health effects

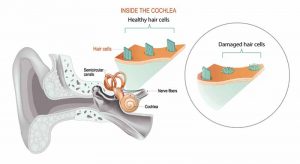

Hearing is a historically undervalued and underserved sense, at least within Western societies. It was not until the mid-20th century—as public awareness of the need for stricter occupational health and safety guidelines grew—that the requirement to preserve it garnered widespread support. Numerous studies subsequently demonstrated strong correlations between sudden or sufficiently prolonged exposure to higher noise levels and temporary or permanent hearing loss, which is generally understood to mean damage to the hairs or nerve cells within the ears, affecting their ability to transmit information to the brain. Other potential consequences may involve tinnitus, characterized by ringing or other “phantom noises” in the ears, and hyperacusis, which refers to the increased sensitivity to ordinary sounds.

[2]

[2]Today, most people are well-acquainted with the auditory health effects of high noise levels, as well as the associated “safe limits” established for workplaces. Basically, the risk of hearing loss is immediate when the noise level approaches or exceeds 120 decibels (dB) (e.g. from an explosion), while impairment due to lower levels (e.g. from machinery) usually requires longer exposure; for example, a 15-minute exposure to 100 dB or a two-hour-long exposure to 90 dB.2 In the U.S., the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) recommended exposure limit (REL) is 85 A-weighted decibels (dBA) averaged over an eight-hour work shift.3 As noise increases above that level, the allowed exposure time decreases.

[3]

[3]Non-auditory health effects

Fewer people are aware of the potential non-auditory health risks of lower-level noises, below the established thresholds that one associates with hearing impairment. Over the past decades, researchers started exploring the impacts of various sources (e.g. road, rail, and airplane traffic), and the results are mixed. As a general, non-specific stressor, noise has been found to have non-auditory health effects—such as changes in hormones, sweat response, metabolism, heart rate, and blood pressure, as well as outcomes related to its disruptive effect on sleep and immune response—but not consistently. Further, it is difficult to conclusively link noise to, for instance, the development of heart disease, which can also be linked to other health-related factors.

This is not to say there are no such adverse impacts; in fact, some experts maintain the question is no longer whether noise causes cardiovascular disease, for example, but to what extent.

Noise sensitivity

Research consistently demonstrates noise level alone is not a sufficiently strong indicator of potential health consequences. One must also take into consideration additional characteristics such as frequency, predictability, complexity, duration, and the meaning of the noise in question, the listener’s acoustic environment (including ambient or background spectra and levels), and the listeners themselves—perhaps first and foremost, their sensitivity to noise.

A growing body of literature dealing with the non-auditory effects of lower-level noise differentiates between “noise exposure” and “noise sensitivity.” In a review, Brown et al. cites Schreckenberg et al., who found that noise affects different people differently, as well as Shepard et al., who “found noise level does not necessarily determine noise annoyance, but rather other factors play a role, in particular, noise sensitivity.”4 The findings, presented by Park et al. (2017) in a paper titled, “Noise sensitivity, rather than noise level, predicts the non-auditory effects of noise in community samples: a population-based survey,” show the effects—specifically those pertaining to mental wellbeing—on an individual’s health are more strongly correlated with their sensitivity to noise than other variables (e.g. sociodemographic factors, medical illness, duration of residence, and so on).

Although the focus of such research largely remains an assessment of the person (a comprehensive description of the acoustic conditions is seldom provided), distinguishing between noise exposure and noise sensitivity has advanced understanding of the non-auditory effects of noise and led more researchers to question whether different people react similarly—or the extent to which they do—when exposed to lower-level sources, and to focus on the psychological, as well as the physical, impacts.

[4]

[4]Neurodiversity and noise

Researchers are also exploring how individual differences come into play within the workplace. For example, neurological differences—such as autism spectrum disorder (ASD), attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), dyslexia, and dyspraxia, as well as neurological challenges resulting from brain injury—can impact how individuals process sensory information (e.g. increase noise sensitivity), which in turn affects their social and occupational functioning. Employees can also suffer from misophonia, or other auditory hypersensitivities, whereby common sounds such as chewing, breathing, and repetitive tapping—or stimuli related to such sounds—elicit a strong emotional response ranging from mild irritation to anxiety, anger, disgust, and even significant distress.

[5]

[5]While offering privacy pods and headsets might seem like relatively simple solutions, these tactics may not send the desired message of inclusivity

or be the most sustainable given neurominorities already comprise 15 to 20 percent (some suggest as high as 40 percent) of the population, and that figure is expected to rise in the coming years.5, 6 More holistic approaches to acoustical design will not only better accommodate increasing numbers of neurodiverse individuals, they will also greatly benefit those considered neurotypical because no one is immune to environmental stressors and, particularly, to noise.

POEs highlight ‘poor acoustics’

Indeed, post-occupancy evaluations (POEs) such as those conducted by the Center for the Built Environment (CBE) show that “poor acoustics”—predominantly lack of speech privacy and noise from conversation—consistently ranks as the top source of workplace dissatisfaction. Parkinson et al.’s recent in-depth analysis of more than 600 office buildings with 62,000 occupants in the CBE’s database reveals that, of all sources of dissatisfaction, acoustics most strongly interferes with self-reported work performance—a conclusion supported by numerous studies demonstrating its negative impact on focus.7 Additional well-documented effects include: productivity losses due to increased errors and time spent on tasks, diminished capacity for creativity, innovation, and problem solving, reduced collaboration due to fear of being overheard and disrupting others, and increased use of electronic communication and headsets, as well as requests to work remotely.

“Poor acoustics” also takes a psychological and physical toll on employees, who report feeling uncomfortable, edgy, irritable, and unmotivated in noisy workspaces. By stimulating the sympathetic nervous system (i.e. the “fight-or-flight” response), noise can have cardiovascular-, gastric-, endocrine-,

and immune-related impacts. The attempts to overcome this constant environmental stimulus causes cognitive strain and stress, contributing to mental health issues such as anxiety and burnout, which can, in turn, make people even more sensitive to acoustical disturbances. Since people are typically an organization’s largest cost, one must also consider the financial impact of workforce “unwellness”—including stress, disengagement, and illness—which GWI estimates may cost the global economy 10 to 15 percent of economic output annually.

Workplace design that respects rather than challenges the senses by, for example, mitigating disruptive noise, supports the health and wellbeing of all an organization’s members and allows everyone to achieve their full potential. In other words, it is not only “neurodiverse design,” but also considered “good design.”8

Acoustics and ‘good design’

People principally rely on sound level, reverberation time, absorption, sound insulation, and vibration isolation to quantify the acoustic properties of materials, assemblies, and spaces, but those metrics do not indicate or assess a person’s acoustical experience. Large POE datasets such as those the CBE has compiled, on the other hand, do empower building design professionals to make practical, data-driven decisions to help achieve occupant-centric goals, such as focus, comfort, privacy.

Parkinson et al. points out that bridging the gap between this data and actionable insights to improve workspaces “may require a shift in focus from the determinants of overall satisfaction to common sources of occupant dissatisfaction.” It also involves centering design on the main way employees use these facilities. According to Gensler’s U.S. Workplace Survey 2022, most employees primarily use the office as a dedicated space for focused work, and they spend most of their time working independently. Moreover, 69 percent of these tasks demand a significant level of concentration. The firm concludes that supporting this type of work provides “a crucial foundation of the workplace experience,” but, at the same time, their data indicates workplace effectiveness in this regard has declined to the lowest levels since 2008.9

[6]

[6]Design trends have increasingly favored collaboration in workspaces over the last decade. Given that “poor acoustics” is the number one cause of dissatisfaction and focus work is the primary objective of those using offices, it is clearly time to prioritize occupants’ need for quiet and privacy. Fortunately, spaces designed to facilitate concentration have also proven to be more conducive to collaboration than those primarily designed for only collaboration.

Of course, offering adjunct spaces where employees can join their colleagues for face-to-face time is also important. Considering 72 percent of adults report feeling lonely—and hyposensitive neurodiverse individuals require more, rather than less, sensory stimulation to focus and feel safe in social engagement—communal areas that help build relationships and offer more “energetic” acoustics also support mental health and wellbeing.10 Organizations can also offer additional aural experiences such as relaxation rooms that employ natural sounds to stimulate the parasympathetic nervous system (i.e. a “rest and digest” state). Providing a variety of spaces with different auditory features from which to select has the added benefit of increasing occupants’ feelings of control over their work environment.10

That said, self-awareness is likely insufficient to achieve occupant-centric goals because there are aspects of the environment that occupants may not consciously recognize or fully appreciate as being either beneficial or detrimental to health and wellbeing. At the same time, these aspects are not adequately accounted for in current noise-rating systems or even in recently developed building standards geared toward wellbeing.

Indeed, most employees’ understanding of acoustics primarily stems from noise exposure theory and its focus on level or, more colloquially, “loudness.”11 Hence, the answer to the question “What constitutes ‘good acoustics’ within the workplace?” is often simply “an environment with little to no noise.” Given this viewpoint, the notion of intentionally increasing ambient sound levels to achieve a quieter environment—or, rather, one occupants will perceive as quiet—may seem counterintuitive, but, contrary to popular understanding, a person’s perceptions of sound have less to do with the lowest level of sound humans they can hear, and more to do with their ability to identify and discern sounds within their acoustic environment.

Sound versus noise

To move acoustic design forward, one must first address what is perhaps the most pervasive source of confusion in architectural acoustics: misuse of the terms “sound” and “noise.”12

Although these words are often used interchangeably—as are “ambient sound” and “ambient noise”—“sound” refers to acoustic waves (or, in the case of occupants, the transportation of physical vibrations in the air within the human ear’s frequency range of 20 to 20,000 Hz), while “noise” is essentially “unwanted and/or harmful sound” or, in Kryter’s words, “audible acoustic energy…that is unwanted because it has adverse auditory and nonauditory physiological or psychological effects on people.”13

The classification of some types of sounds as “unwanted” is key to achieving “good acoustics.” Many studies into non-auditory health effects consider noise emitted by industrial and environmental sources, as well as transportation (e.g. road, rail, and airplane traffic); however, in spaces with higher occupant densities such as offices, occupant-generated noise is the most significant cause of acoustical dissatisfaction. Traditional assessment methods seldom make provisions for this source (focusing on building-related systems, services, and utilities) and, because of its complex nature, building professionals are not easily able to account for it during design—that is, unless they put sound to work.

[7]

[7]Sound is continuously produced and present in the built and natural environment—by individuals and those around them, office equipment, and essential building systems, services, and utilities that support other environmental parameters within the space—and it also enters from the outdoors. This understanding—that everyone is constantly surrounded by acoustic energy—helps in exploring more nuanced acoustical concepts, such as the “audibility” of sound and its beneficial uses (i.e. how it can be leveraged to support occupant needs), and not only the adverse effects of noise.

The Masking Effect

As an example, imagine a room that has sufficient insulation to prevent noise transmission, allowing one to solely focus on the interior ambient conditions. Occupancy is limited to one person. The resulting space is one in which the overall background sound level is exceptionally low. Now imagine what this space may or may not sound like. Most would describe it as “silent.” In practice, environments designed to meet this extreme criterion are highly specialized acoustical facilities, such as anechoic chambers, and occupants often describe their experience as uncomfortable, unsettling, or even intolerable for reasons that include being able to hear their own heartbeats and other bodily functions, given the lack of “interfering” sound. Similarly, ambient “silence” (in this case, low or intermittently low background sound levels) in an office makes surrounding conversations and acoustical disturbances easier to hear.

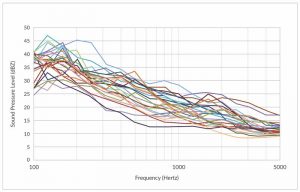

Other sounds present within a space, particularly its ambient acoustic conditions, such as background sound (or lack of it), affect the perception of sounds in that space. The physics behind this effect was documented as early as the 1950s and referred to as the Masking Effect. To be clear, it does not explain human acceptance or assessment of sounds, only the ability to hear, identify, and differentiate between them. It is an effect routinely experienced in everyday life due to things such as blowing wind, running water, a murmuring crowd, and HVAC, but rarely thought about in the context of the built environment. That said, the only time such ambient sound typically falls below the threshold of hearing is when special effort is made to reduce it, as in an anechoic chamber or recording studio. Since background sound is present in just about every inhabited environment, in addition to making people more vulnerable to acoustical disturbances, its absence can also feel “unnatural.”

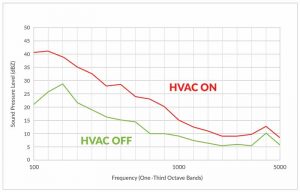

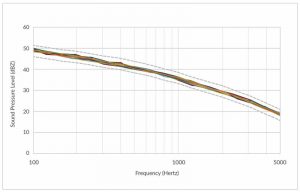

As interest lies in conditions conducive to acoustical comfort rather than discomfort, the reader is now invited to add a level of background sound to the imaginary room, such as that produced by HVAC. Technically, this sound corresponds with the typical maximum limits (30 to 55 dBA) defined in the ASHRAE Handbook – HVAC Applications. Since frequency plays a role in determining comfort, with low, mid, or high frequencies potentially causing discomfort due to their rumbling, buzzing, or hissing content, the reader should also apply an appropriate spectrum—a concept at the heart of most noise-rating systems, which depend on a reference contour to assess whether the ambient acoustic conditions are spectrally “neutral.”

However, because building-related systems, services, and utilities are designed to support other functional needs (e.g. thermal, air quality, water, lighting) and sound is simply a byproduct, it varies (temporally) according to the optimal performance and efficiency conditions of the various components. At the same time, the positioning and arrangement of these sources, which encompass elements such as ductwork and piping, exert a significant influence on how acoustic energy is distributed within a facility, particularly in terms of its spatial transmission. In other words, in practice, the background sound (or noise) produced by such equipment is not temporally or spatially consistent, or spectrally neutral.14 Building design professionals can only strive to ensure overall levels do not exceed acceptable maximum limits.

[8]

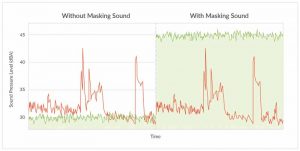

[8]To dependably manage the overall level and spectral distribution of background sound within the built environment—thus ensuring the minimum limit needed for speech privacy, as well as the frequency range required to effectively mask speech and a wide range of noises, while maintaining occupant comfort—one must employ a sound-masking system: an acoustical solution intended to manage the ambient acoustic conditions in a space.15

Masking technology has come a long way since its inception in the 1960s; with the introduction of small control zones and precise computer tuning, appropriately trained technicians are now able to control its output with precision. When handled correctly, the sound achieved within the space not only minimizes the disruptive impact of noise and protects the privacy of conversation, but it also does it consistently and unobtrusively. In this case, sound has a “damping” effect, rather than acting as a stimulus, as it either entirely masks noise or diminishes its disruptive impact. This reduction in the dynamic range, which denotes the variation in sound levels over time or the difference between the loudest and quietest sounds measured over a period, plays a crucial role in mitigating distraction and discomfort. Consequently, it helps in averting the activation of the sympathetic nervous system responsible for the “fight or flight” response.

Implementation of masking sound

The importance of managing beneficial background sound within interiors is increasingly recognized in standards, guidelines, and codes worldwide, but obstacles remain in understanding how one should handle it. Despite its role as one of the three pillars of effective architectural acoustical design (i.e. the “C” in the “ABC Rule,” which stands for “cover” or, more accurately, “control”), sound masking remains the most poorly understood. In the absence of industry standards pertaining to design and performance, notably significant variations also exist among the available sound-masking systems and implementation methods.

While the concept is straightforward, one cannot achieve the benefits of the Masking Effect via a “plug and play” electronic system. As the generated sound is affected by the facility’s interior layout, furnishings, and finishings, effective application requires not only diligent design through small control zones, technical expertise in sound masking and general acoustics, and specialized equipment (ANSI Type 1 one-third octave analyzers and Class 1 calibrators), but also precise field tuning in line with ASTM E1573-22, Standard Test Method for Measurement and Reporting of Masking Sound Levels, Using A-Weighted and One-Third Octave-Band Sound Pressure Levels. Further, to be accountable to the construction specifications and, ultimately, to the client, the contractor must properly measure and report the tuning technician’s results.

It is worth noting sound masking’s current location (27 51 19 Sound Masking Systems) within MasterFormat, Division 27–Communications means it is often managed from a communications (A/V) perspective rather than an acoustical one. Although audio and masking systems use similar components (e.g. electronics, cable, loudspeakers), their purpose is fundamentally different: the former distributes communication, while the latter is intended to obscure it. Masking also fulfils other goals outside the scope of communication systems such as acoustical comfort. Given the lack of industry standards, project teams are heavily reliant on experts and contractors to provide guidance and masking delivery. Signaling in MasterFormat that masking is an acoustical technology rather than an audio system would afford building professionals the opportunity to carefully consider what parties are best suited to provide advice and handle masking implementation.

![Figure 1 Once background sound conditions are defined using a sound-masking system (blue circles indicate loudspeakers), other acoustical strategies and materials can be added to the design to maintain those conditions as closely as possible by managing transmission of sound into or out of spaces. This type of ‘masking first’ approach typically reduces wall (e.g. sound transmission class [STC] ratings; height) and ceiling (e.g. noise reduction coefficient [NRC] and ceiling attenuation class [CAC] ratings) requirements, as well as those of other acoustical materials (e.g. absorptive panels).](https://www.constructionspecifier.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/12/health_Image_9-300x175.jpg) [9]

[9]

In other words, application of masking also informs decisions regarding wall construction (e.g. sound transmission class [STC] ratings; full or partial height), ceiling selection (e.g. noise reduction coefficient [NRC] and ceiling attenuation class [CAC] ratings), and other acoustical materials such as absorptive panels, tying it thereby more closely with architectural and acoustical design.

In conclusion

Failure to incorporate appropriate acoustical solutions raises concerns for occupants’ physical and psychological safety, along with potential impacts on organizational diversity and productivity. While most building design professionals are familiar with the “ABC Rule”—and, indeed, that one must use a holistic approach to achieve the desired experiential outcome—the role of background sound (the “C”) remains widely misunderstood.

Fine-tuning the acoustical vernacular helps identify acoustic conditions that provoke adverse effects, and how sound can be used to mitigate them. At the same time, looking to recent research to further the understanding between “acoustics” and “human perception” (specifically within the realm of psychoacoustics, even prior to the complexities introduced by the architectural environment) provides a framework for achieving “optimal acoustic conditions”—one formerly obscured by reluctance to speak openly about mental health and neurological differences, as well as the ease with which noise complaints were dismissed as neurotic, weak, or self-centered.

While the vagaries of individual perception are worth exploring, the interest ultimately lies in the practice of acoustics within a communal workplace environment. Addressing the issues the POE data has brought forth—and transforming occupant-centric objectives into quantifiable acoustic criteria—requires a nuanced exploration of sound’s attributes. This encompasses not only its level, but also its spectral, spatial, and temporal qualities, within the context of common objectives such as achieving acoustic comfort and maintaining acoustical privacy.

[10]

[10]Although acoustical comfort is a relatable concept, many consider it more subjective than objective. By quantifying the degree to which humans can perceive sound—and, in the case of masking technology, conforming to a preferred spectrum—the Masking Effect demonstrates why this belief is misinformed. Similarly, the argument for acoustical privacy is often perceived as niche and only relevant to occupants of certain spaces (e.g. in medical exam rooms), even though the conditions required to achieve it are the same as those needed for focus (e.g. in open plan offices).

In the end, sound is all around and the physics relating the Masking Effect are omnipresent conditions. Building design professionals can intentionally shape those conditions using the type of noninformational broadband sound that forms the backdrop of occupants’ daily lives, but optimized for productivity, health, wellbeing, and satisfaction.

Notes

1 Refer to T. Sheridan and K. Van Lengen, “Hearing Architecture: Exploring and designing the aural environment[11],” Journal of Architectural Education, November 2003.

2 The decibel (dB) is typically used to express the “loudness” of sound. The scale is logarithmic, so although the numerical difference between two levels might appear small, the actual difference is exponential. For example, the energy of an 80 dB sound is 1,585 times greater than one of 48 dB. Expressed in terms of distance, if 80 dB is equivalent to 1.6 km (1 miles), 48 dB is only 1 m (3 ft).

3 The A-weighted level (dBA) provides better indication of occupants’ impression of sounds than the decibel (dB) because it applies a set of “corrections” to instrument-measured sound levels that account for our sensitivity to different frequencies. For example, if two tones (e.g. 200 Hz and 1,000 Hz) differ in non-weighted level (e.g. 60.85 dB and 50 dB, respectively), people may still perceive them as having equal “loudness” (e.g. 50 dBA) because humans are less sensitive to lower-frequency sounds than high ones.

4 Refer to B. Brown, P. Rutherford and P. Crawford, “The role of noise in clinical environments with particular reference to mental health care: A narrative review,” International Journal of Nursing Studies, vol. 52, no. 9, 2015.

5 See V. Drummer, A. Taylor and S. Basque, “Designing for Neurodiversity: Creating spaces that are inclusive of all,” www.stantec.com/en/ideas/topic/buildings/designing-for-neurodiversity-creating-spaces-inclusive-of-all, 2013[12].

6 To help prevent hearing loss related to use of a personal audio system (PAS) such as a mobile phone and headset, one should follow the recommendations outlined in ITU-T H.870 (03/2022), Guidelines for safe listening devices/systems. It is also important to note that noise-cancelling headphones block speech and background noise equally, meaning the relative difference between them remains the same; they do not reduce speech intelligibility.

7 Refer to T. Parkinson, S. Schiavon, J. Kim, and G. Betti, “Common sources of occupant dissatisfaction with workspace environments in 600 office buildings,” Buildings and Cities, 4(1), 2023.

8 See note 5.

9 Refer to the Gensler Research Institute, “Returning to the Office” briefing based on data captured by Gensler’s U.S. Workplace Survey 2022.

10 To avoid interruption from external sources, the intentional introduction of aural experiences in spaces requires careful control of their boundaries and the acoustic conditions within them.

11 Level is a single-value metric arrived via the sum of its frequency components, measured over time. Its simplicity—in terms of both measurement and as a concept—is one reason why it is commonly used by those in the building industry (e.g. owners, architects, designers, engineers), but there are nuances to this parameter that often cause confusion (e.g. as sound is measured over time, a constant sound and an intermittent sound measured over a certain sampling period may be equal in level) and the numeric value offers little insight into the characteristics of a noise, only its relative “loudness.” Sounds can also vary in spectrum (e.g. rumbly, buzzy, hissy), temporal characteristics (e.g. constant, fluctuating, surging, intermittent), as well as spatially (e.g. overhead, adjacent, throughout a space).

12 For more on this topic, see “Rethinking Acoustics: Understanding silence and quiet in the built environment[13]” by V. Koukounian and N. Moeller in the August 2020 issue of The Construction Specifier.

13 Refer to D. Fink, “A New Definition of Noise: Noise is unwanted and/or harmful sound. Noise is the new ‘second hand smoke,” Acoustical Society of America’s Proceedings of Meetings on Acoustics, January 2019.

14 Similarly, music and nature sounds cannot be relied upon to mask noise and speech adequately or consistently. It is also important to note that they are also subject to personal preference, and occupants’ response to nature sounds (e.g. running water) can be further affected by lack of associated visual stimulus (e.g. a waterfall). Where appropriate (e.g. in lobbies and relaxation rooms), these sounds can be used in conjunction with masking; the latter establishes the foundation for speech privacy and noise control, while the former achieves other auditory goals.

15 For more on this topic, see “In Pursuit of Acoustical Equity: Controlling temporal, spectral, and spatial properties of sound[14]” by V. Koukounian and N. Moeller in the May 2021 issue of The Construction Specifier.

Authors

Niklas Moeller is the vice-president of K.R. Moeller Associates Ltd., manufacturer of the LogiSon Acoustic Network and MODIO Guestroom Acoustic Control. He has more than 25 years’ experience in the sound-masking industry. Moeller can be reached via email at nmoeller@logison.com.

Niklas Moeller is the vice-president of K.R. Moeller Associates Ltd., manufacturer of the LogiSon Acoustic Network and MODIO Guestroom Acoustic Control. He has more than 25 years’ experience in the sound-masking industry. Moeller can be reached via email at nmoeller@logison.com.

Viken Koukounian, PhD, P.Eng., is director of engineering at Parklane. He is an active and participating member of many international standardization organizations, such as the Acoustical Society of America (ASA), ASHRAE, ASTM, the Green Building Initiative (GBI), and the International WELL Building Institute (IWBI), the Standards Council of Canada (SCC), and also represents Canada at International Organization of Standardization (ISO) meetings. He completed his doctorate at Queen’s University (Kingston, Ontario, Canada) with foci in experimental and computational acoustics and vibration. Koukounian can be reached via email at viken@parklanemechanical.com.

Viken Koukounian, PhD, P.Eng., is director of engineering at Parklane. He is an active and participating member of many international standardization organizations, such as the Acoustical Society of America (ASA), ASHRAE, ASTM, the Green Building Initiative (GBI), and the International WELL Building Institute (IWBI), the Standards Council of Canada (SCC), and also represents Canada at International Organization of Standardization (ISO) meetings. He completed his doctorate at Queen’s University (Kingston, Ontario, Canada) with foci in experimental and computational acoustics and vibration. Koukounian can be reached via email at viken@parklanemechanical.com.

- [Image]: https://www.constructionspecifier.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/12/health_Opener.jpg

- [Image]: https://www.constructionspecifier.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/12/health_Image_2.jpg

- [Image]: https://www.constructionspecifier.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/12/health_Image_1.jpg

- [Image]: https://www.constructionspecifier.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/12/health_Image_3.jpg

- [Image]: https://www.constructionspecifier.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/12/health_Image_4.jpg

- [Image]: https://www.constructionspecifier.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/12/health_Image_5.jpg

- [Image]: https://www.constructionspecifier.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/12/health_Image_6.jpg

- [Image]: https://www.constructionspecifier.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/12/health_Image_7.jpg

- [Image]: https://www.constructionspecifier.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/12/health_Image_9.jpg

- [Image]: https://www.constructionspecifier.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/12/health_Image_8.jpg

- Hearing Architecture: Exploring and designing the aural environment: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/277172178_Sound_Awareness_and_Place_Architecture_from_an_Aural_Perspective

- www.stantec.com/en/ideas/topic/buildings/designing-for-neurodiversity-creating-spaces-inclusive-of-all, 2013: https://www.stantec.com/en/ideas/topic/buildings/designing-for-neurodiversity-creating-spaces-inclusive-of-all

- Rethinking Acoustics: Understanding silence and quiet in the built environment: https://www.constructionspecifier.com/rethinking-acoustics-understanding-silence-and-quiet-in-the-built-environment/

- : Controlling temporal, spectral, and spatial properties of sound: https://www.constructionspecifier.com/in-pursuit-of-acoustical-equity/

Source URL: https://www.constructionspecifier.com/exploring-how-sound-and-noise-impact-wellbeing-in-office-design/