Fire resistance and prevention in wood buildings

by sadia_badhon | January 6, 2020 11:04 am

by Mariah Seaboldt, PE

[1]

[1]It may seem counterintuitive to study the fire resistance of a combustible material, but wood construction has been the focus of such research for decades. The desire to harness the benefits of wood buildings, while still maintaining a safe environment, has fueled studies into both light-frame wood and mass timber assemblies. The results of this research have informed past building codes and are leading to changes in upcoming ones, allowing more projects to capitalize on the cost, schedule, and environmental advantages of wood construction. As the popularity of wood grows, construction safety practices are also receiving greater emphasis in an effort to mitigate fire hazards during one of the most vulnerable periods of a building’s lifetime.

Overview of mass timber

Light-frame wood construction is common across the United States. However, more projects are now using mass timber in lieu of other building materials. Various types of mass timber products are available, including cross-laminated (CLT), nail-laminated (NLT), glue-laminated (glulam) timbers, and structural composite lumber (SCL). More information regarding typical mass timber elements and common applications can be found in “Mass Timber in North America” by Think Wood.

Mass timber buildings are capable of providing a level of fire-resistance comparable to steel and concrete. As a result, approved changes to the 2021 International Building Code (IBC) introduce additional timber construction classifications (Type IV-A, Type IV-B, and Type IV-C) and will allow three-hour rated mass timber structures to be built up to 18 stories in height (Type IV-A construction). These recently approved changes can be viewed on the International Code Council[2]’s (ICC’s) website.

[3]

[3]Images courtesy AKF Group

While there is a growing desire to utilize mass timber, several stumbling blocks stand in the way of widespread use of these products. Due to the predominant use of steel and concrete, designers, owners, and authorities having jurisdiction (AHJs) may not be familiar with the fire research associated with mass timber. Additionally, while the new provisions of 2021 IBC expand on the allowances for mass timber buildings, formal code adoption by individual jurisdictions can be a lengthy process. As a result, the public’s perception of large-scale buildings has been built on a foundation of steel and concrete. Although the concept of tall, mass timber buildings is new, increasing awareness and use of the material can help change this perception.

Wood behavior in fire conditions

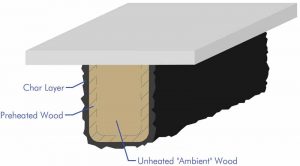

In order to understand the different fire-resistance capabilities of light-frame wood and mass timber, designers should understand the basic fire behavior of the material. When exposed to the heat of fire, all wood undergo a thermal degradation reaction called pyrolysis. As wood is heated, the material decays into volatile gases and leaves behind a layer of char. Flaming ignition of wood is actually the ignition of the volatile gases released during the pyrolysis process. For more details on the science of pyrolysis, read the Society of Fire Protection Engineers’ (SFPE’s) Handbook of Fire Protection Engineering.

The char layer created during pyrolysis insulates the remaining layers of wood and slows the overall degradation of the member. A portion of the wood directly adjacent to the char layer experiences higher temperatures than the rest of the wood (i.e. preheated zone). As described in the American Wood Council’s (AWC’s) “Technical Report No. 10,” the base of the char layer and the start of the preheated zone are accepted to have a temperature of approximately 300 C (550 F). Beyond the preheated zone, the wood has a temperature close to its initial ambient temperature. This area is usually referred to as “ambient,” “normal,” or “cold” wood. In general, wood members with larger cross sections endure the heat of fire for longer durations, since it takes more time to reduce the size of the ambient zone to the point of critical structural failure.

Basic fire resistance criteria

Whether using mass timber, light-frame wood, or any other material, IBC bases fire-resistance ratings on the testing and exposure criteria of ASTM E119, Standard Test Methods for Fire Tests of Building Construction and Materials, or Underwriters Laboratories (UL) 263, Standard for Fire Tests of Building Construction and Materials. ASTM E119 is commonly referenced for testing of fire-resistance ratings, though the two standards are effectively the same. IBC permits fire-resistance ratings to be substantiated by subjecting assemblies to ASTM E119 or UL 263 testing[4], or through calculations, prescriptive designs, or other engineering analysis (IBC 2018, 703.3, “Methods for determining fire resistance”).

[5]

[5]ASTM E119 testing procedures involve exposing the assembly to increasing furnace temperatures based on the standard’s specified time-temperature curve. Some assemblies must also withstand a hose stream test to evaluate the assembly’s ability to remain intact during fire conditions. A full list of specified furnace temperatures and acceptance criteria for various types of assemblies can be found in ASTM E119.

Component Additive Method for calculated fire resistance

ASTM E119 is also used as a reference for comparing the fire resistance of assemblies and materials. As detailed in “Analytical Methods for Determining Fire Resistance of Timber Members” by Robert H. White in the SFPE handbook, the Component Additive Method (CAM) was developed by the National Research Council Canada (NRC) to determine the fire-resistance ratings of various building elements. CAM was created by correlating data from fire tests of light-frame wood assemblies to ones tested to ASTM E119.

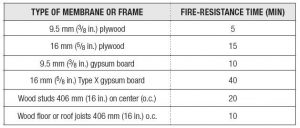

Through CAM, the protective membranes and framing of an assembly are assigned individual fire-resistance times. The total fire-resistance rating of the assembly is determined by adding the times allotted to each individual component. CAM is only applicable to light-frame wood assemblies and is limited to the specific components tested as part of NRC’s research. Examples of fire-resistance times assigned to various light-frame components are summarized in Figure 1. For additional fire-resistance times and more information on CAM, consult 2018 IBC 722.6, “Wood assemblies,” and “Analytical Methods for Determining Fire Resistance of Timber Members” by Robert H. White.

[6]

[6]Calculating fire-resistance ratings using CAM is allowed by IBC to demonstrate the fire ratings of light-frame wood, and can be used in lieu of specifying an assembly tested to ASTM E119 (2018 IBC 703.3 and 722.6). Although CAM can be used to obtain fire-resistance times between 20 and 90 minutes, IBC limits the approach for assemblies with a maximum fire-resistance rating of one-hour (2018 IBC 722.6.1.1, “Maximum fire-resistance rating”). Additionally, IBC 722.6 limits the application of CAM to wood framing spaced a maximum of 406 mm (16 in.) on center (o.c.) and to wood joist construction only.

Calculated fire resistance using the National Design Specification for Wood Construction

Since the CAM approach is only applicable to light-frame wood assemblies, alternate methods must be used for mass timber assemblies. IBC also allows the use of chapter 16, “Fire Design of Wood Members,” of the American National Standards Institute (ANSI)/AWC, National Design Specification (NDS) for Wood Construction, to calculate the fire resistance of exposed wood members (2018 IBC 722.1, “General”). NDS procedures are an expansion of the calculation methods originally developed by T.T. Lei at NRC in the 1970s. Lei’s methods were first recognized by model building codes in the United States in 1984 and were adopted by all the three legacy codes organizations—the Building Officials and Code Administrators International, Inc. (BOCA), International Conference of Building Officials (ICBO), and Southern Building Code Congress International (SBCCI). More information on the development and history of the NDS calculation procedures can be found in AWC’s “Technical Report No. 10.”

Overview of the NDS calculation method

The NDS method for determining fire resistance is based on a calculation of the char layer depth at the time of required fire-resistance (e.g. one-hour). A nominal char rate of 0.6 mm/min (1.5 in./h) is used to represent standard fire exposure (i.e. ASTM E119 exposure). Using the nominal or a selected char rate, and the equations provided in chapter 16 of NDS, designers can calculate the char depth in a given member.

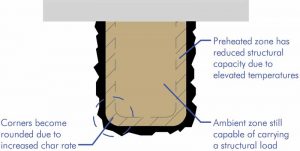

While NDS calculations use a nominal char rate, the corners of rectangular members experience increased charring due to the impinging heat transfer from two directions. As a result, the corners of wood members become rounded during a fire. Additionally, the preheated zone has reduced structural capacity due to elevated temperatures. As a result of these conditions, NDS specifies the use of an effective char depth that is 20 percent deeper than the calculated level. Using the effective char depth to determine the reduced cross section of the member, chapter 16 of NDS outlines procedures for determining the remaining average ultimate strength of the member. If the ultimate strength is sufficient for the supported loads, the member is considered to be capable of providing the applicable fire-resistance rating.

Comparison of NDS calculations and fire tests of wood members

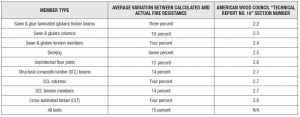

Part II of AWC’s “Technical Report No. 10” compares approximately 145 fire tests of wood members to the calculated fire resistance of the member using chapter 16 of NDS. The tests included both large timber members as well as smaller, light-frame options. As shown in Figure 2, the calculated fire-resistance times were within three to 19 percent of the measured fire resistance of the members. The fire test results illustrate the NDS calculation procedure is capable of accurately estimating the fire resistance of exposed wood members.

Additional methods of determining fire resistance

[7]

[7]The NDS calculation procedures are only applicable to fire-resistance ratings for exposed wood up to two-hours (NDS 16.2, “Design Procedures for Exposed Wood Members,” and IBC 722.1). Therefore, the assemblies using protective membranes and assemblies needing ratings greater than two hours must have alternate methods of substantiating fire resistance. For example, the new Type IV-A construction classification requires a three-hour primary structural frame and cannot contain any exposed wood (2021 IBC 602.4, “Types of Construction”). Therefore, Type IV-A construction elements must be tested to ASTM E119, or have ratings substantiated through an engineering analysis.

A growing number of mass timber assemblies have undergone fire testing to demonstrate fire-resistance ratings. WoodWorks[8] has assembled a database of fire-tested assemblies, including penetration and firestopping systems. Several of the tested assemblies achieve a three-hour fire-resistance rating when coupled with noncombustible membranes such as gypsum. The use of gypsum as a protective membrane can benefit both light-frame and mass timber assemblies. However, where gypsum is required for added protection, wood buildings may be vulnerable prior to installation of the material. As a result, safe construction practices play a pivotal role in protecting wood buildings from fire.

[9]

[9]Fire prevention during construction

As discussed in previous sections, mass timber elements are capable of achieving substantial fire resistance. However, higher fire-resistance ratings and more robust construction types require the usage of noncombustible membranes over the wood elements (e.g. Type IV-A and IV-B construction). Similarly, gypsum is used in light-frame construction to provide a protective membrane for the wood studs. Where noncombustible membranes are required, they are often installed some time after the installation of wood elements, leaving the latter exposed for a period of time. As a result, construction site safety becomes a crucial component of the fire-protection strategies for wood buildings.

Several recent construction fires in light-frame buildings have heightened concerns regarding the use of wood construction. The article “Danger: Construction” in the National Fire Protection Association (NFPA) Journal provides details on several of these fires. As a result of the increased fire risk during construction, many jurisdictions and organizations are advocating for more oversight of construction practices. Compliance with NFPA 241, Standard for Safeguarding Construction, Alteration, and Demolition Operations, is often required through a jurisdiction’s fire code, and is referenced by both the International Fire Code (IFC) and NFPA 1, Fire Code (2018 IFC 3301.1, “Scope,” and 2018 NFPA 1 section 16.1, “General Requirements”). However, it is not consistently applied to projects, even though it has existed in some form since 1930.

NFPA 241 requires owners to develop a construction fire safety program and to designate a fire prevention program manager to enforce it. The purpose of the fire safety program is to ensure construction operations are conducted in accordance with the practices established in NFPA 241 (Figure 3).

Additionally, the 2019 edition of NFPA 241 includes provisions specific to wood construction that are intended to mitigate the threat of arson. NFPA 241 now gives the AHJ authority to require guard service for buildings with combustible materials exposed during construction, and that are greater than 12 m (40 ft) in height (NFPA 241, section 7.2.5, “Site Security.”)

NFPA 241 for tall wood buildings

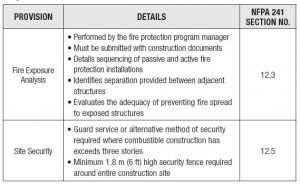

Chapter 12, “Safeguarding Construction Operations for Tall Timber Structures,” of NFPA 241-19 is specific to tall timber buildings (i.e. mass timber). Two significant provisions of the new chapter involve site security and a fire exposure analysis of the building. According to section 12.3, “Fire Exposure Analysis,” of NFPA 241-19, the analysis must:

- be performed by the fire protection program manager;

- be submitted with construction documents;

- detail sequencing of passive and active fire protection installations;

- identify separation provided between adjacent structures; and

- evaluate the adequacy of preventing fire spread

to exposed structures.

[10]

[10]Section 12.5, “Site Security,” of NFPA 241-19 requires:

- guard service or alternative method of security where combustible construction exceeds three stories; and

- minimum 1.8-m (6-ft) high security fence around the entire construction site (Figure 4).

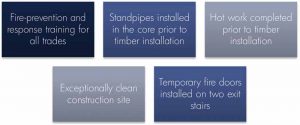

The new provisions in NFPA 241 come after successful fire management on several tall timber projects around the world. For example, the 18-story Brock Commons in Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada, utilized a detailed fire management plan to mitigate the fire risk of the high-rise mass timber structure. As discussed by naturally:wood (naturally:wood provides information about environmentally sourced forest products from British Columbia, Canada) in the “Brock Commons Tallwood House Construction Overview,” a layer of protective drywall was required for the building’s construction type. However, the mass timber elements needed to be fully dry prior to installation of the drywall, causing the latter’s installation to lag behind the timber. To mitigate the amount of exposed wood during construction, the fire management plan specified a maximum of six floors of exposed wood at a time. The plan also included several additional safety measures such as:

- fire-prevention and response training for all trades;

- standpipes installed in the core prior to installation of mass timber;

- hot work completed prior to timber installation;

- exceptionally clean construction site; and

- temporary fire doors installed on two exit stairs.

Through the use of safety practices such as those employed for Brock Commons, as well as those specified in NFPA 241, construction sites with exposed wood can effectively mitigate fire hazards prior to the installation of passive and/or active fire protection systems.

[11]

[11]Conclusion

Not all wood projects require protective membranes. As illustrated by NDS calculations and the research presented in AWC’s “Technical Report No. 10,” exposed wood can provide substantial fire resistance. As a result, provisions for exposed wood are recognized by IBC and will be expanded in upcoming editions of the code. However, where enhanced fire resistance is required, gypsum or other protective membranes can be used to afford an additional level of fire protection. Buildings relying on noncombustible membranes for added protection should develop comprehensive construction fire management plans to ensure a safe jobsite.

However, construction site safety should not only apply to wood buildings. All buildings undergoing construction have an elevated fire risk due to the hazardous activities, the accumulation of materials, and/or the lack of permanent fire protection features. Utilizing the provisions of NFPA 241 can protect all types of buildings from construction fires, resulting in a greater level of safety for both the building and construction personnel.

Mariah Seaboldt, PE, is a registered fire protection engineer in Massachusetts. She has a bachelor’s degree in civil engineering and a master’s degree in fire protection engineering from Worcester Polytechnic Institute. Seaboldt is part of the architectural code consulting team at AKF Group in Boston where she specializes in building, fire, life safety, and accessibility code consulting for both existing building renovations and new construction projects. Seaboldt can be reached at mseaboldt@akfgroup.com[12].

- [Image]: https://www.constructionspecifier.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/bigstock-Asti-Italy-An-A-277355152.jpg

- International Code Council: http://www.iccsafe.org

- [Image]: https://www.constructionspecifier.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/Wood-beam-sketch_Revit_1.jpg

- UL 263 testing: http://iq2.ulprospector.com

- [Image]: https://www.constructionspecifier.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/FIgure-1.jpg

- [Image]: https://www.constructionspecifier.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/Figure-2.jpg

- [Image]: https://www.constructionspecifier.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/Wood-Beam-Cross-Section_2.jpg

- WoodWorks: http://www.woodworks.org/wp-content/uploads/Inventory-of-Fire-Resistance-Tested-Mass-Timber-Assemblies-Penetrations.pdf

- [Image]: https://www.constructionspecifier.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/NFPA-241.jpg

- [Image]: https://www.constructionspecifier.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/FIgure-4.jpg

- [Image]: https://www.constructionspecifier.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/Brock-Commons.jpg

- mseaboldt@akfgroup.com: mailto:mseaboldt@akfgroup.com

Source URL: https://www.constructionspecifier.com/fire-resistance-and-prevention-in-wood-buildings/