HORIZONS

HORIZONS

Josh Newland

An all-too-familiar problem in the construction industry involves outdated drawing sets that do not reflect how a building has been built. Like other document control issues, this is usually a function of not having the necessary information in the right place at the right time. Once drawings are produced, cumulative errors from the document management process, along with missing markups and revisions, can result in a highly inaccurate and disjointed set of documents.

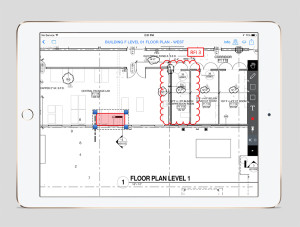

On the other hand, real-time as-builts are the product of an iterative information sharing loop that can include related detail callouts, requests for information (RFIs), punch items, and markups. This enables drawings to reflect the project’s current status as it changes, and provides owners with accurate as-built drawings of the project on completion.

As-built drawings are intended to represent the finished condition of a newly built structure. The term “as-builts” is often used interchangeably with “record documents”—although legal parsings generally suggest some differences between the two.

Architects and designers are usually responsible for compiling this final drawing set, but because they are not always onsite to see work being performed first-hand, they rely on drawing markups from contractors in the field. This means owner-architect agreements typically include language relieving architects of liability for any inaccuracies. Contractual documents, therefore, are likely to place responsibility for as-built accuracy with the contractor. Often, contract language also specifies changes be “redlined”—that is, modifications to the original design must be clearly identifiable.

Not only are contractors liable for the accuracy of as-built drawings, but it is also not unusual for payments to contractors to be withheld when an in-progress set of as-built drawings is deemed deficient. These ramifications make it critical for an ongoing, complete, and correct as-built record to be kept.

The traditional process

Historically, all information has been tracked and captured using paper documents. In the pre-electronic world, the construction industry put sophisticated systems in place to organize and track their printed materials. Rigid rules governed every aspect of construction documents, from timing of printing to assembly requirements. Even so, keeping up effective communications between team members and maintaining updated documents proved almost impossible.

Paper forms are now being replaced by electronic files, not only for original construction documents, but also for the contractually specified drawings of record (which are usually requested to be in PDF or computer-aided design [CAD] format). In the field, however, it is still common for markups to be done on paper. Still, for a commercial construction project, the number of documents required can be in the thousands. Transferring accurate information from one document set to another is an enormous challenge.

As with document management on the administration end, standard procedures for drawing markups have been followed in the field. Typically, design drawings––either digital files or paper copies––are sent from architects to general contractors, then distributed in sets to subcontractors. Subcontractors usually have the drawings printed if they are not in paper format already, and then distribute those papers to site personnel and to staff in the job trailer. Markups and notes are redlined on the drawings in the field, and RFIs are posted, with each group of subcontractors marking their own drawing set.

When revised drawings from the architect’s office show up on the jobsite, all personnel have to ‘slip-sheet’ their drawing sets. This means replacing updated pages––sometimes hundreds of them––and hand-copying any applicable notes or markups. At the end of the job, the general contractor collects redlined sets from all major subcontractors, or has all subcontractors copy their redlines to a set, and this information is sent to the architect’s and engineer’s offices to have the markups put into CAD.

In theory, this workflow captures all relevant information. However, in practice, the process often breaks down, usually in the distribution and slip sheeting of revisions. In fact, it is common to find contractors building off of outdated paper drawings on almost every jobsite.

There a two statements to which I take exception as not being standard practice as defined by the CSI Project Resource Manual and the relevant AIA documents.

” Architects and designers are usually responsible for compiling this final drawing set ” and “At the end of the job, the general contractor collects redlined sets from all major subcontractors, or has all subcontractors copy their redlines to a set, and this information is sent to the architect’s and engineer’s offices to have the markups put into CAD”.

These responsibilities are the Contractor’s under Article 3.10.2 of A201. Unless separately contracted to perform this work under B141, Item 2.8.3.20, the Architect’s responsibility is limited to reviewing the “record” set as a submittal.

There are two statements to which I take exception as not being standard practice as defined by the CSI Project Resource Manual and the relevant AIA documents.

” Architects and designers are usually responsible for compiling this final drawing set ” and “At the end of the job, the general contractor collects redlined sets from all major subcontractors, or has all subcontractors copy their redlines to a set, and this information is sent to the architect’s and engineer’s offices to have the markups put into CAD”.

These responsibilities are the Contractor’s under Article 3.10.2 of A201. Unless separately contracted to perform this work under B141, Item 2.8.3.20, the Architect’s responsibility is limited to reviewing the “record” set as a submittal.