by Brian Clarke, AHC, CDT, CSI

Given the unfortunate rise in security breaches, especially active shooter and other violent incidents, it is more important than ever for schools, hospitals, office buildings, and other facilities to keep occupants safe and control foot traffic while still being code-compliant. This can be accomplished with access control using electrified locks or panic hardware, along with many other configurations of electronic door hardware.

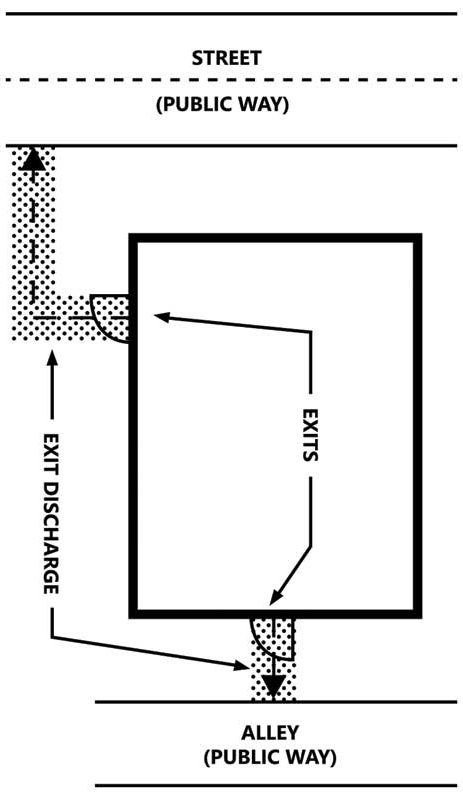

Even a simple buzzer used in conjunction with an electric strike can provide remote release of a locked door by administration. When specifying a high-use building, such as a school or office, it is important for architects and specifiers to keep in mind any access control must allow free means of egress, fire protection, and accessibility. An accessible means of egress, as defined by the International Building Code (IBC), is a “continued and unobstructed way of egress travel from any point in

a building or facility that provides an accessible route to

an area of refuge, a horizontal exit, or a public way.”

There are three parts to a means of egress:

- exit access (starts at any location from within the building and ends at the exit);

- exit (typically a door leading to the outside or an enclosed exit stairway in a multistoried building); and

- exit discharge (the path from the exit to a public way).

IBC requires at least two means of egress from all buildings and spaces within buildings. Spaces and buildings with 500 occupants or more are required to have at least three means of egress, and for those with more than 1000 occupants, there need to be at least four. (However, when adopting a model code like IBC, some jurisdictions amend the code to reflect local practices and laws.)

Image courtesy Hager Companies

When specifying door hardware for a high-use building, the level of security needed for that facility will help shape the type of product required. Building flow or traffic is a good starting point for facility directors and architects to determine which doors will be the main entry points to and from the building.

The National Association of State Fire Marshals (NASFM) has guidelines addressing door security devices for classroom openings. These guides are being incorporated into standards from American National Standards Institute (ANSI) and International Code Council (ICC), as well as IBC, National Fire Protection Association (NFPA) 101, Life Safety Code, and NFPA 80, Standard for Fire Doors and Other Opening Protectives. They mandate doors should:

- provide immediate egress by having locking devices located between 865 and 1220 mm (34 and 48 in.) above the finished floor (AFF);

- not require any special knowledge or effort, key or tool, or tight grasping, twisting, or pinching to operate, and allow use to be accomplished with one operation;

- be easily lockable in case of emergency from within the classroom with an authorized credential (e.g. key, card, code, fob, or fingerprint) and without opening the door; and

- be lockable and unlockable from outside the door with an authorized credential.

Code restrictions and dangers of barricade devices

Unfortunately, there has been a rise in the recommendation of so-called ‘barricade devices,’ which temporarily block doors so people cannot enter or leave. They prevent free means of egress that allow occupants to vacate the building quickly if needed. These products, while securing a door opening from unwanted ingress, do not take into account the fire and building codes that have been put in place to maintain safety for occupants and first responders.

A few states have passed laws allowing these devices to be used as viable options, against the advice of their state fire marshals, building code officials, and various other experts. A report by the Ohio Board of Building Standards, which was critical of the devices, states they are “unlisted, unlabeled, and untested.” Lawmakers in Ohio approved barricade devices following testimony from manufacturers of the devices and parents of schoolchildren. Several door and hardware industry experts also testified against the use of such products, but to no avail.