High-use buildings and the selection of code-compliant hardware

by Katie Daniel | October 4, 2017 2:36 pm

[1]

[1]by Brian Clarke, AHC, CDT, CSI

Given the unfortunate rise in security breaches, especially active shooter and other violent incidents, it is more important than ever for schools, hospitals, office buildings, and other facilities to keep occupants safe and control foot traffic while still being code-compliant. This can be accomplished with access control using electrified locks or panic hardware, along with many other configurations of electronic door hardware.

Even a simple buzzer used in conjunction with an electric strike can provide remote release of a locked door by administration. When specifying a high-use building, such as a school or office, it is important for architects and specifiers to keep in mind any access control must allow free means of egress, fire protection, and accessibility. An accessible means of egress, as defined by the International Building Code (IBC), is a “continued and unobstructed way of egress travel from any point in

a building or facility that provides an accessible route to

an area of refuge, a horizontal exit, or a public way.”

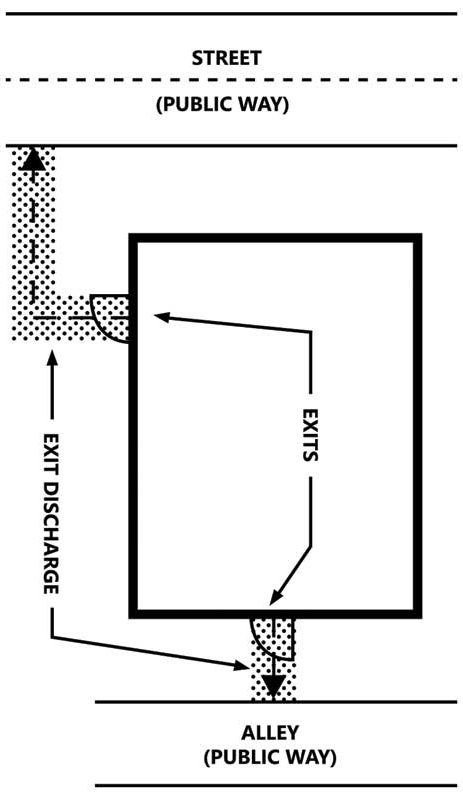

There are three parts to a means of egress:

- exit access (starts at any location from within the building and ends at the exit);

- exit (typically a door leading to the outside or an enclosed exit stairway in a multistoried building); and

- exit discharge (the path from the exit to a public way).

IBC requires at least two means of egress from all buildings and spaces within buildings. Spaces and buildings with 500 occupants or more are required to have at least three means of egress, and for those with more than 1000 occupants, there need to be at least four. (However, when adopting a model code like IBC, some jurisdictions amend the code to reflect local practices and laws.)

[2]

[2]Image courtesy Hager Companies

When specifying door hardware for a high-use building, the level of security needed for that facility will help shape the type of product required. Building flow or traffic is a good starting point for facility directors and architects to determine which doors will be the main entry points to and from the building.

The National Association of State Fire Marshals (NASFM) has guidelines[3] addressing door security devices for classroom openings. These guides are being incorporated into standards from American National Standards Institute (ANSI) and International Code Council (ICC), as well as IBC, National Fire Protection Association (NFPA) 101, Life Safety Code, and NFPA 80, Standard for Fire Doors and Other Opening Protectives. They mandate doors should:

- provide immediate egress by having locking devices located between 865 and 1220 mm (34 and 48 in.) above the finished floor (AFF);

- not require any special knowledge or effort, key or tool, or tight grasping, twisting, or pinching to operate, and allow use to be accomplished with one operation;

- be easily lockable in case of emergency from within the classroom with an authorized credential (e.g. key, card, code, fob, or fingerprint) and without opening the door; and

- be lockable and unlockable from outside the door with an authorized credential.

Code restrictions and dangers of barricade devices

Unfortunately, there has been a rise in the recommendation of so-called ‘barricade devices,’ which temporarily block doors so people cannot enter or leave. They prevent free means of egress that allow occupants to vacate the building quickly if needed. These products, while securing a door opening from unwanted ingress, do not take into account the fire and building codes that have been put in place to maintain safety for occupants and first responders.

A few states have passed laws allowing these devices to be used as viable options, against the advice of their state fire marshals, building code officials, and various other experts. A report[4] by the Ohio Board of Building Standards, which was critical of the devices, states they are “unlisted, unlabeled, and untested.” Lawmakers in Ohio approved barricade devices following testimony from manufacturers of the devices and parents of schoolchildren. Several door and hardware industry experts also testified against the use of such products, but to no avail.

[5]

[5]Photo © Shutterstock

The Builders Hardware Manufacturers Association (BHMA) has addressed the classroom locking issue by proposing a change to the 2018 edition of IBC and clarifying codes already in place. Hopefully, the new language will help educate those who still believe barricade devices are the solution. However, these codes will only go into effect when adopted by a specific state or jurisdiction.

With the BHMA proposal, the 2018 edition of IBC will address school security by including the following:

1010.1.4.4 Locking arrangements in educational occupancies. In Group E and Group B education occupancies, egress doors from classrooms, offices and other occupied rooms shall be permitted to be provided with locking arrangements designed to keep intruders from entering the room where all the following conditions are met:

- The door shall be capable of being unlocked from outside the room with a key or other approved means;

- The door shall be openable from within the room in accordance with Section 1010.1.9;

- Modifications shall not be made to listed panic hardware, fire door hardware, or door closers.

1010.1.4.4.1 Remote operation of locks. Remote operation of locks complying with Section 1010.1.4.4 shall be permitted.

The proposal clarifies:

This code change will require all Group E classroom doors to be lockable from the inside of the classroom preventing entry to the classroom, without the need to open the door. This proposal does not prescribe specifically how the door is to be lockable from inside the classroom.

In the aftermath of the Columbine tragedy in 1999, a ‘classroom intruder’ function was developed allowing a lock to be secured from the interior of a classroom, while still allowing free egress from the inside and entry from the outside using a key. This type of function is readily available from lock manufacturers at a similar cost as the traditional classroom function locksets.

Additional requirements state the door is to be unlockable and readily openable inside the classroom without the use of a key or special knowledge or effort, as required in IBC Section 1010.1.9, “Door Operations.” Subsections of 1010.1.9 include requirements for hardware height and configuration. An additional requirement of this proposal is the classroom door is to be unlockable and openable from outside the classroom by a key or other lock credential.

This proposal balances the challenges of providing protection to students and teachers in schools while allowing free and immediate means of egress at all times without the use of keys, tools, or special knowledge.

Both NFPA 101 and the International Fire Code (IFC) have similar wording under development. These codes will not take effect immediately, and the debate around the use of barricade devices will continue to be controversial long after these codes are implemented.

[6]

[6]Photo © Shutterstock

Controlled egress within healthcare facilities

While there are no nationally adopted emergency management standards for schools, hospitals are required to undergo a safety inspection to receive licensure and state accreditation. Like school administrators, it is in the hands of hospital leaders to make the best, most-informed decision for individuals’ safety and security needs.

There were many important changes between the 2000 and 2012 editions of NFPA 101, some of which specifically allow hospitals and healthcare facilities to address one of the biggest challenges they face—the ability to safely and effectively prevent the escape and abduction of their most vulnerable and at-risk patients. Fortunately, new sections specific to healthcare facilities have been added to NFPA 101 allowing egress doors in certain types of healthcare units to be locked in the direction of egress, using an application commonly referred to as ‘controlled egress.’ This application is allowed where the clinical needs of patients require specialized security and/or protective measures.

Healthcare facilities are also required to designate ‘smoke compartments’ (i.e. spaces within the facility enclosed by smoke barriers on all sides, including the top and bottom). At least two smoke compartments are required for every story used for sleeping rooms for more than 30 people, which helps restrict movement of smoke and allows for more flexibility in transferring patients. These additions (NFPA 101 Sections 18.2.2, “Means of Egress Components,” and 19.2.2, “Means of Egress Components”) give healthcare facilities the ability to improve security for areas such as behavioral health, memory care, and pediatric and maternity units,

as well as emergency departments.

When controlled egress locking devices are used, staff must have the ability to readily unlock doors at all times. Stringent safeguards must be in place to help reduce the potential threat to life safety these locks create. Fail-safe electrified locks must be used to unlock doors upon loss of power or ensure activation of the smoke detection system. Only one controlled egress lock is permitted on each door, and locks must be able to be unlocked remotely from within the designated locked smoke compartment.

Accessibility in office buildings

Extra attention is being paid to life-safety protocols and procedures, especially emergency egress from tall buildings. Although emergency egress is hopefully

a rare issue in a building’s life, everyday accessibility issues must be considered in building design. The requirements of the 2010 Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) Standards for Accessible Design and ICC/ANSI A117.1, Accessible and Usable Buildings and Facilities, are good resources for understanding code compliance and the correct operation of door hardware.

Architects, engineers, and contractors have historically relied on the ICC’s model codes to provide minimum requirements. Requirements in the codes are addressed during the design process, when it is easier and more cost-effective to correct errors. Higher levels of compliance with accessibility requirements are achieved through local review and inspections performed by the code official. Finding problems after the building is occupied can lead to expensive retrofits, as well as delays in use of the building.

Hardware and ‘intelligent’ integration

Hardware is a crucial element in buildings, as door openings provide means of egress, security, and building accessibility. Facility managers must think about how and for what the building will be used when deciding on door hardware and access control solutions.

BHMA developed a minimum performance grading system for all hardware, including locksets. This grading system is also accredited by ANSI. Under this system, a Grade 1 lock is heavy-duty, Grade 2 is medium, and Grade 3 is for residential use. Many commercial buildings use different-grade hardware in different areas of the building; for example, a Grade 1 lock is generally used on exterior doors, while a Grade 2 lock can be used on interior doors with less traffic.

For many K–12 school districts, healthcare facilities, and commercial buildings, maintaining a secure building while providing safe and code-compliant egress is a top priority, but costs are still a major concern. With new generations of access control (e.g. wire-free installation and virtual networks) being introduced, the need to reconfigure an existing building can be significantly reduced while still providing high security. Extensive research and development, production, and quality management have shaped platforms that can be used to build various customizable access control solutions.

[7]

[7]Photo courtesy Salto Industries

Offline electronic systems

With these offline systems, a portable programming device transfers audit data from the locks to the software, as well as updates the locks with user credentials and calendar information. These systems require the administrator or the maintenance department to visit the individual locks to make any changes, which can be cumbersome as well as time-consuming. In these cases, the lock is the component that ‘makes the decision’ to allow or refuse a given credential.

Data-on-card systems

These systems provide flexible security by using a credential to transmit data between offline devices and online management systems. All user-related access information is stored on smart credentials (i.e. cards), which act as carriers for the network. This eliminates the need to have wired or wireless locks at every secured opening and drastically reduces the overall cost of the access control system. In these cases, the card has the access rights and tells the offline lock how it should act.

Wireless and hard-wired systems

Wireless and hard-wired systems are used when immediate checking on the openings is needed. They are designed to offer real-time monitoring and control—including, in many cases, lock-down abilities—and are highly recommended for institutional, educational, and commercial applications requiring enhanced levels of security.

The type of credentials should also be considered. Maternity wards, for instance, might prefer a bracelet credential to allow for stronger security for parents and newborns. Universities can reduce costs by having students use their phones as credentials.

Conclusion

Doorways and door hardware are very critical components to every building, as they aid safe passage in and out—especially in times of emergency. Building codes have been developed to address emergency concerns, but unfortunately, most codes are reactive measures to a traumatic event, rather than being proactive. Therefore, building codes are constantly evolving, and the number of updates and changes can be overwhelming. Understanding complex codes and changing building needs can be difficult, yet it is crucial to the safety of those who use the building. That is why it is especially important for facility managers and other decision-makers to choose code-compliant doors and hardware, and to reach out to experts in case of confusion. Code compliance is not just following the law—it can also help save lives.

Brian Clarke, AHC, CDT, CSI, is director of architectural specifications and technical support for Hager Companies. He has more than 15 years of experience in specification writing and architectural hardware consulting services, including design development assistance, code compliance, security collaboration, and hardware submittal review. Clarke can be reached at bclarke@hagerco.com.[8]

- [Image]: https://www.constructionspecifier.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/Access-office-bldg.jpg

- [Image]: https://www.constructionspecifier.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/2nd_para_exitdischarge-e1507141396541.jpg

- guidelines: http://naosfm30.wildapricot.org/resources/Documents/NASFM%20Documents/NASFM%20Classroom%20Door%20Security%2020150322.pdf

- report: http://www.doorsecuritysafety.org/Forms/Foundation/Final-Report-072315-Ohio-Board-of-Bldg-Standards.pdf

- [Image]: https://www.constructionspecifier.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/controlled-egress-healthcare.jpg

- [Image]: https://www.constructionspecifier.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/4th_para_blueprints.jpg

- [Image]: https://www.constructionspecifier.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/hdw-intell-integration.jpg

- bclarke@hagerco.com.: mailto:bclarke@hagerco.com

Source URL: https://www.constructionspecifier.com/high-use-buildings-selection-code-compliant-hardware/