by Kerry VonDross

Providing a good acoustical environment is critical to the well-being of people occupying interior spaces; especially for rooms having hard-surfaced, highly reflective enclosures.

Volume resonators—acoustical devices comprising a hollow cavity connected to the atmosphere via an aperture—are one means of achieving suitable environments for human occupancy and superior audibility for social interaction.

Origins of cavity resonators

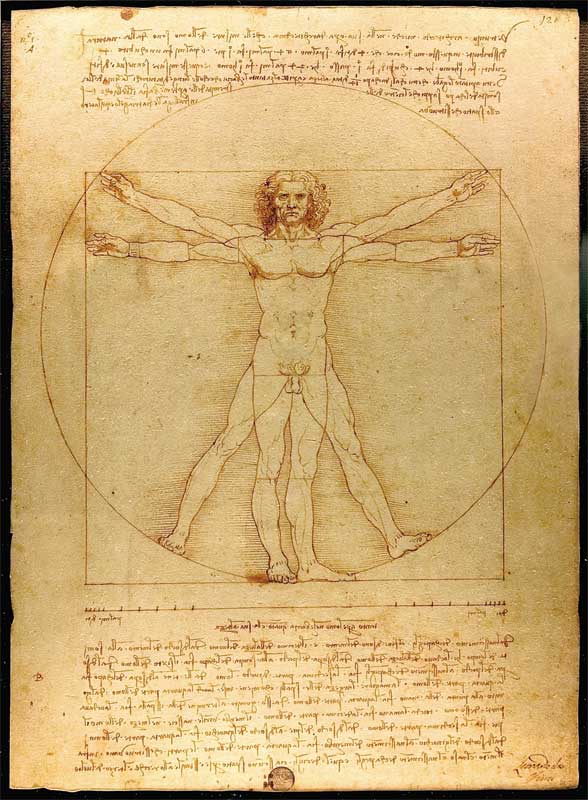

The Vitruvian Man by Leonardo da Vinci (c. 1492) is one of the world’s most iconic images. It depicts the human body inscribed within the fundamental geometric patterns of the circle and the square. Da Vinci’s illustration of the ideal human body is based on concepts of geometry and human proportions as developed by the Roman architect and engineer Marcus Vitruvius Pollio (1st century BC) in his 10-volume work, De Architectura. Vitruvius’ texts, also known as the Ten Books on Architecture, are the earliest known treatise on architectural theory. He wrote guiding principles about the design of Roman structures, their materials and building methods, as well as precepts concerning the aesthetic and practical effects of architecture on the lives of citizens.

In his Book V, Vitruvius describes the proper arrangement and construction principles of various public places such as Roman forums and basilicas; emphasizing their design should follow the classic principles of symmetry and harmony and adopt proportions that imitate nature. Vitruvius also provides design strategies for building a proper community theater including site and orientation, foundation, enclosures, seating, and acoustics.

Sympathetic to the importance of good sound quality in a theatrical venue, Vitruvius provided design insights toward improving acoustic intelligibility. He wrote on the science of sound transmission through air movement, how stage voices best reach the audience, reflective vocal sounds and echoes, and on “methods increasing the power of the voice in theaters through the application of harmonics.”

Due to the provenance of Vitruvius’ writings, he is often regarded as the father of architectural acoustics. He is most noted for his examination of using echéa (literally: echoers) as instruments for improving the sound in theaters. These “sounding vessels” were bronze urns. Their size and number were proportionate to the volume of the amphitheater, distributed in tiers with equal space between them, placed free-standing in hollowed arched niches, and supported on wedges to minimize damping. Uttered stage voices, upon entering the cavities of these sounding vessels, were to cause it to resonate in unison with the voice frequencies and produce an increased harmonious note, thereby increasing the clearness of voice sounds for the audience.

There is debate among acousticians whether the echéa were sympathetic resonators that increased power, or instead, acted as sound absorbers that reduced reverberation and improved sound quality. However, both resonance and absorption may have taken place in the ancient theaters. The lively, free-perched echéa may well have acted in a reverberatory function as harmonic amplifiers. Additionally, the rigid stone masonry, arched-opening niches constructed to house the sounding vessels performed as built-in bass traps, dampening low-frequency resonances and improving the listening environment.

Leonardo da Vinci’s pen and ink drawing of The Vitruvian Man.

Photo courtesy Wikimedia Commons

Acoustic pots in medieval churches

The difficulty of sound intelligibility in rooms having hard-surfaced walls was evidently understood by church and cathedral builders in medieval times. Their religious structures were ultimately purposed for hearing spoken words and song of the human voice, but these majestic edifices were constructed with solid, permanent, stone and brick masonry—materials that produce strong, clear reflections, but are disastrous for interior room acoustics.

Pulpit voices emanating from the apse and liturgical song from the choir hall reverberated through the church before reaching the oblong naves where the listening laity was seated. These spaces were constructed with semi-circular walls, arched, vaulted, and domed ceilings, which exasperated audibility by prolonging sound resonance.

The idea of utilizing clay, acoustic pots—volume resonators—to control the room acoustics and improve sound perception was employed in church architecture from the 10th to the 16th centuries.

Urns and earthenware pots were placed within the buildings’ structural matrix. Instead of exploiting free-standing vibratory bronze urns, clay jars and pots of various sizes were implanted into the stone and brick masonry walls and vaults of more than 300 churches throughout Europe, with the vast majority located in France.

Again, there is debate amongst archeologists and acousticians regarding the ancient intention of these acoustic pots, whether they were for amplification of the voice or to dampen sound vibrations. However, with recent understanding of room acoustics and modern acoustical testing equipment, the evidence leans toward the point of view that acoustic pots provided absorption, decreased resonance time, and improved human voice perception within these highly reverberating environments.

The church builders had a practical knowledge of utilizing earthen pots effectively as volume resonators to control room acoustics. Not just one size, but various-sized pots and jars were utilized together to broaden resonant frequency absorption. Dust, potsherds, straw, and peat were found placed in the wall pots to baffle the resonator, thereby expanding the effectiveness of absorption at greater frequencies. The clay pots were made with their volume tuned towards low-frequency absorption—a sound control difficult to capture by other available means.

As explained by medieval architecture expert Andrew Tallon, “In the past, furniture, such as tapestries, wooden panels, or paintings, was present in large quantities in churches. It absorbed some of the reverberation. Notice the pots are tuned at low frequencies for which absorption by furniture is less efficient.”1

Built-in-the-structure volume resonators became a noise abatement tool for improving sound quality in hard-surfaced rooms (natural echo chambers amplifying generated noise and garbling sound perceptibility).