Acoustical privacy is key

The reactions of building occupants are captured using psychoacoustic metrics, some of which are subjective (e.g. surveys evaluating comfort, distraction, perceived productivity) and others that are objective (e.g. intelligibility, audibility).

Research shows one’s overall acoustical satisfaction is strongly correlated with acoustical privacy, a concept with clear ties to the workplace, but one that is also relevant to other environments. For example, surveys of multi-unit residences demonstrate links between acoustical privacy and annoyance, fatigue, and sleeping problems (e.g. due to noise from traffic and neighbors) (consult B. Rasmussen and O. Ekholm’s paper ‘Is noise annoyance from neighbours in multi-storey housing associated with fatigue and sleeping problems?’ in Proceedings of the 23rd International Congress on Acoustics [ICA], Aachen, Germany, 2019). In other words, although people tend to equate acoustical privacy with speech privacy, the former is not limited to the intrusion of speech content; it also considers the audibility of unintelligible speech and other types of noise.

That said, it is challenging to use acoustical privacy as a starting point for a conversation about acoustical equity. The science around acoustical privacy is not sufficiently nuanced; it is not yet addressed by a standardized metric or even a proposed methodology.

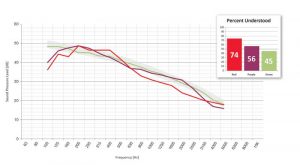

Speech privacy, on the other hand, is both well-defined and measurable (e.g. using articulation index or speech privacy class). Therefore, it is a psychoacoustic metric that can be used in both theoretical (i.e. to illustrate the concept of acoustical equity) and practical ways (i.e. to set expectations during design and estimate occupants’ subjective impression of the built space). In this case, evaluation of acoustical privacy is effectively a review of the signal-to-noise ratio; it considers an intruding ‘signal’ (speech) and its level relative to the background ‘noise’ (or, rather, sound) in the receiving space (for more information about the differences between ‘noise’ and ‘sound,’ read Viken Koukounian and Niklas Moeller’s article ‘Rethinking Acoustics: Understanding silence and quiet in the built environment’ in the May 2021 issue of The Construction Specifier).

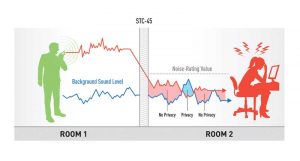

By way of example, see the rooms—and occupants—shown in Figure 1:

- Room 1: The red arrows depict an elevated level of intruding noise, compared to the green arrows. This case represents a well-designed space where the combination of the insulating properties of the wall (STC-45) and the constant background sound level of 40 A-weighted decibels (dBA) ensures the noise is not intelligible and/or audible.

- Room 2: The green arrows depict a lower level of intruding noise. This case represents a space that fails to consider occupant needs and/or expectations. The combination of the insulating properties of the wall (still STC-45) and the existing background sound level (only 30 dBA or less) in the receiving room is insufficient to ensure acoustical privacy. Although the intruding level of the green source is lower than the red example, it remains intelligible and/or audible.

If one were to assume the red and green signals are people speaking, the red talker’s voice carries into Room 1; however, it is masked by the background sound. The listener in that room cannot identify and/or understand speech and the red talker enjoys speech privacy. The green talker’s voice is carried into Room 2; however, it is not masked by the background sound and the listener can identify and/or understand speech. The green talker does not have speech privacy.

There are impacts beyond the one-way speech privacy. It is understood the red talker has speech privacy because the background sound in the adjoining room masks the received level of their voice. However, the red talker’s ‘perception of privacy’ is violated because they can hear the green talker. This discrepancy can cause reactive behavioral changes on the part of the red talker (e.g. lowering of voice, avoiding confidential topics). It is also accepted the green talker does not have speech privacy because the background sound in the adjoining room does not mask the received level of their voice. However, the green talker has a false perception of privacy engendered by the fact they are unable to hear the red talker. This discrepancy can result in breaches of confidentiality, the implications of which can run the gamut—or gauntlet, depending on the consequences—from embarrassment to legal proceedings.

Understanding acoustical equity

One can appraise this situation using the basic dictionary definition of ‘equity’ (i.e. fairness or justice in the way people are treated, per Merriam-Webster) and conclude that the occupants do not have acoustical equity simply by virtue of the fact they do not enjoy equal levels of speech privacy, or even perceived privacy. However, there is more to the concept of equity.

According to conversations occurring in philanthropic circles, equity is also “about each of us getting what we need to survive or succeed—access to opportunity, networks, resources, and supports—based on where we are and where we want to go. Nonet Sykes, director of race, equity, and inclusion at the Annie E. Casey Foundation, thinks of it as each of us reaching our full potential.” Since design impacts one’s well-being and level of functioning, it is one of the factors in life that—in the words of built environment strategist Esther Greenhouse—has the “power to dis-able or enable.” Greenhouse maintains if there is a “poor fit between a person and their environment, the environment acts as a stressor, pressing down on their abilities, pushing them to an artificially low level of functioning.”

Is this information somehow also applicable to the construction of public elementary schools?