Close-up examination of indent fractured stone tiles

A characteristic of indent fractures is there are only cracks in the stone tile where they align with cracks in the thin-set mortar below. A greater number of cracks is exhibited by the thin-set mortar than the stone tiles, as not all cracks extend into or through the stone.

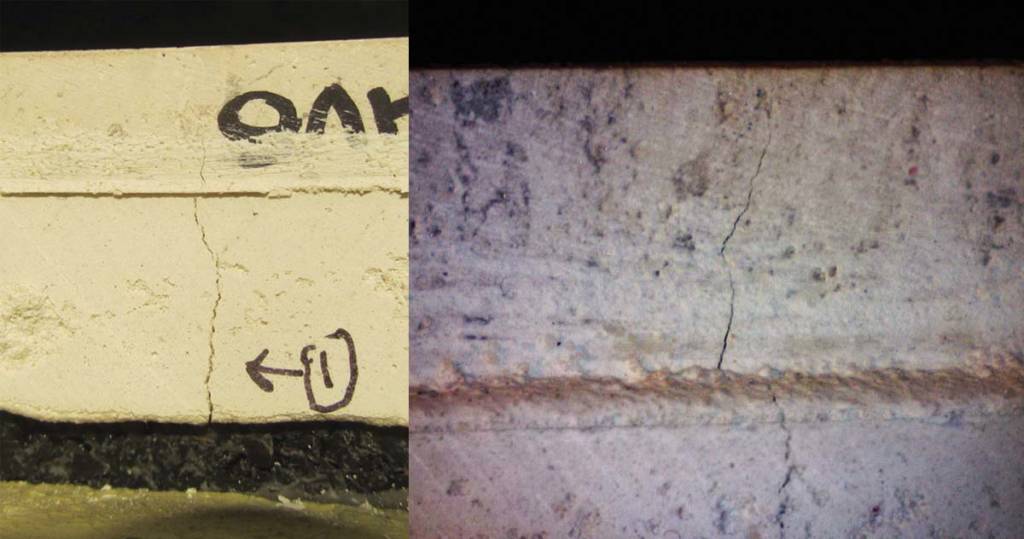

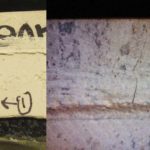

Cracks in the assembly are typically wider at the bottom and narrower at the top, as shown in Figure 5. These features are a strong indication mortar shrinkage cracks initiate at its minimally restrained bottom surface, at the sound-attenuation mat. These features are characteristic of not only indent fractures, but also structural overload of the tile. However, the presence of a coincident indent and curvature at the top surface of the stone tile at the crack is a defining characteristic of an indent fracture resulting from mortar shrinkage, rather than an overload condition.

Evaluating critical factors through mockup assemblies

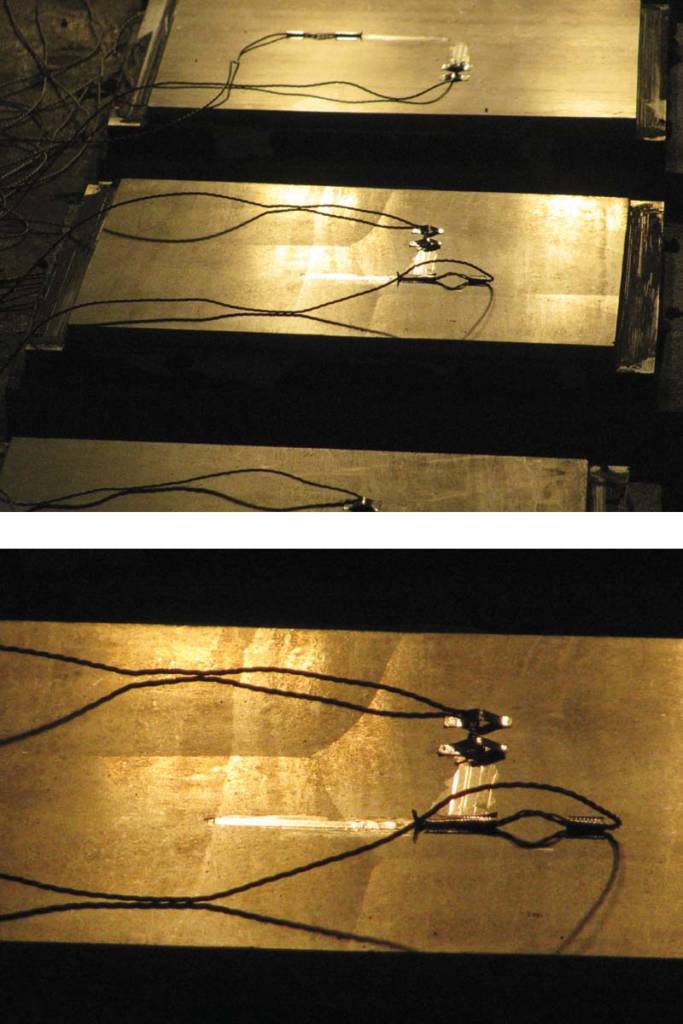

To evaluate the effect of several factors on development of indent fractures, mockup assemblies were fabricated with various combinations of conditions (i.e. stone type, mortar type and thickness, presence of sound-attenuation mat). This enabled replication of the occurrence of indent fractures in a laboratory setting. There are numerous variables in adhered stone tile systems of which only a few were included in the mockups. However, this mockup testing further established the key contributing factors to development of indent fractures.

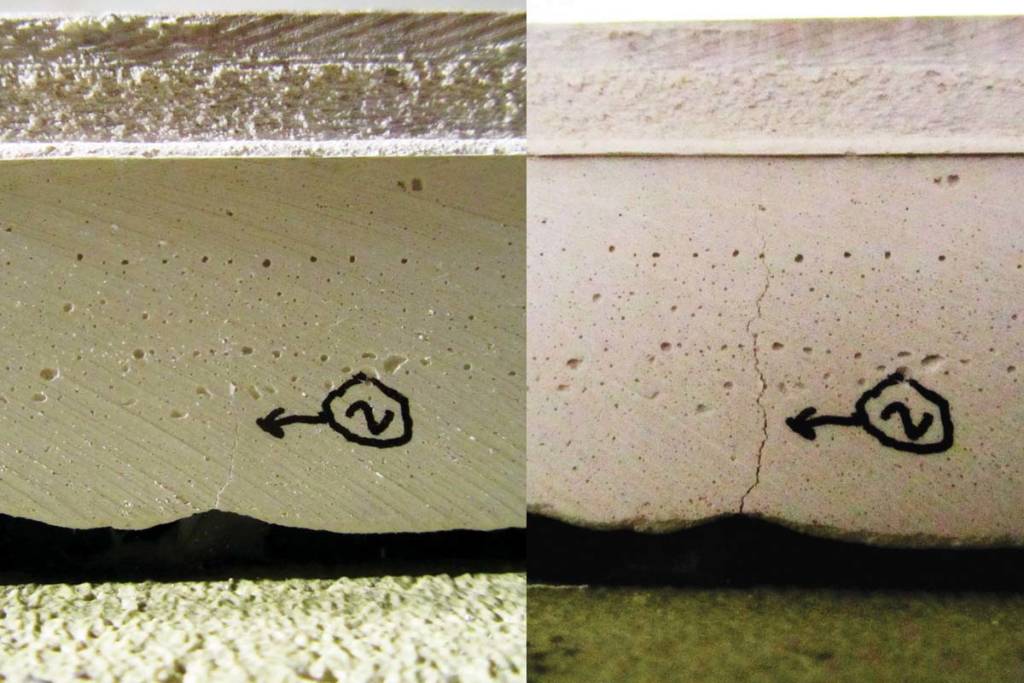

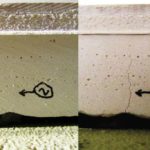

Mockup assemblies with stone types that had the greatest frequency of indent fractures in the actual installation also exhibited indent fractures without exposure to external loading. These were typically first observed between two and four weeks after assembly, and were nearly identical in appearance to those observed in-situ, as typically shown in Figures 6 and 7.

Laboratory mockups also showed indent fractures were far more frequent in assemblies with at least 13-mm (½-in.) thick setting mortar than companion assemblies with 6.4-mm (¼-in.) thick mortar. For example, all eight of the mockup assemblies set on 13-mm (½-in.) thick mortar and sound-attenuation mat for a tile with frequent in-situ distress exhibited indent fracture, while none of the five companion assemblies set using 6.4-mm (¼-in.) thick mortar did. These observations are consistent with reduced stress applied to the tile from reduced mortar thickness.

Indent fractures were also observed at a reduced frequency in mockups without sound-attenuation mat. This indicates a concrete substrate provides greater restraint of the setting mortar—and therefore resistance to mortar shrinkage crack development—than does a more-elastic sound-attenuation mat or any similarly flexible membrane or bond-inhibiting membrane that does not restrain mortar shrinkage.

As was observed in-situ, indent fractures in the mockup assembly tiles aligned with cracks in the mortar, as shown in Figure 8; cracking was also more frequently seen in the mortar than in the stone. The cracks in the mortar appeared to grow wider over time due to continued drying shrinkage of the mortar and stone tile, as shown in Figure 9. Based on these observations, and because no external loading was applied to the mockups, formation of indent fractures can result from mortar shrinkage alone.