| AT A STANDARD’S CORE, PASSIVE DESIGN PRECEPTS |

by Jorge Mastropietro, AIA This author’s childhood home was in Buenos Aires, Argentina, where the summers were naturally hot and sweltering—an average January temperature of 25 C (76 F) and dewpoint averaging 21 C (69 F). When the temperatures descend in winter months, it is mild (12 C [53 F] average) and humid air still endures. Our traditional, vernacular home in the center of the city dated from the 1800s—a type known as a casa chorizo. Like its sausage namesake, the rooms are linked one after another alongside a courtyard. Reflecting back, what I remember most—in addition to the fresh fragrance of jasmine and azaleas in the luminous courtyard—was always feeling comfortable indoors. With cross-ventilation, the house stayed pleasantly cool, even though we didn’t have air conditioning or ceiling fans. Things changed when I moved out and took my own apartment in a brand-new multifamily building with sweeping views across the metropolis. The sun blasted into large windows, and the space became unbearable in the summer. Installing blinds over the windows and a through-wall HVAC unit, which ran 24 hours a day, solved this problem. However, it raised another: The beautiful city views were shrouded in white fabric, and gone were those memorable summer breezes.  It set in stark relief the advantages of the casa chorizo style:

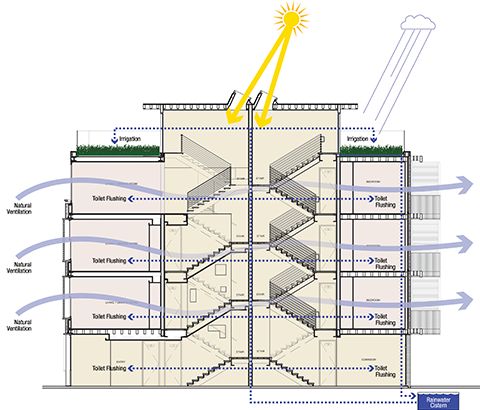

In fact, these are some of the basic passive design strategies that underlie the superior performance expected for the Passive House standards such as Passive House Institute US (PHIUS). Efficiency comes from a measured response to local climate and site conditions to maximize occupant comfort. The same design approaches cut the need for mechanical heating and cooling. Passive design approaches can reduce temperature fluctuations, improve indoor air quality (IAQ), and make a home more enjoyable to live in. As PHIUS notes, architects can implement passive building by incorporating a well-defined “set of design principles used to attain a quantifiable and rigorous level of energy efficiency within a specific quantifiable comfort level.” The group offers five building-science tenets for application to any building type, including:

As it turns out, my childhood’s casa chorizo was embedded with ancient intelligence. As is codified in today’s Passive House certifications, its builders know how to design for both comfort and resource efficiency—using a venerable, passive approach. |

Gita Nandan, RA, LEED AP, is an architect, designer, educator, and community resiliency leader. In 2000, she cofounded the award-winning design firm thread collective LLC, where she is principal. Working in the field for more than 15 years, Nandan has overseen design and construction on a wide range of project types from single-family homes and mixed-use buildings to flood-protection plans and working farms on public housing property. She has been involved in sustainable design policy and code creation groups, serving as a member of the Homes Committee for Urban Green Codes Task Force and the Building Resiliency Task Force, both in New York City. Nandan received her master’s degree in architecture from UC Berkeley and is a registered architect in New York and New Jersey. She can be reached at gita@threadcollective.com.

The Passive House seems like a great step towards greener, more environmentally friendly living. I can’t wait to see some advancement on this! Thanks for sharing this.