The PCR specifies what boundaries should be used in the LCA. (For example, ISO 21930 requires the consideration of energy needed to generate electricity, not simply the electricity used at a manufacturing site.)

From a stakeholder’s perspective, the most versatile EPDs present impacts by each lifecycle phase. This allows users to compare environmental impacts with appropriate boundaries in mind. (This is important if one manufacturer has published a cradle-to-gate EPD and another has published a cradle-to-grave EPD. In this situation, for a meaningful comparison, the user should look at cradle-to-gate impacts, as it is the information available for both products.)

Using EPDs

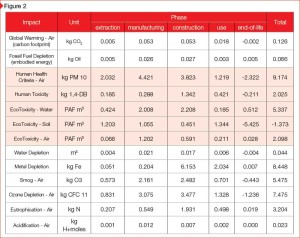

ISO 21930 has requirements regarding which impact categories must be included in EPD impact category tables. For example, Figure 2 shows an impact category table from an EPD for brick made with the alternative ingredient of fly ash, rather than fired-clay or shale. The white items are categories required by ISO, while the highlighted categories are additional categories required by the specific PCR used for the LCA for this EPD. As discussed, PCRs ensure each EPD (in the product category) shows impacts in the same categories, determined using similar methods.

Before environmental considerations became paramount, design professionals typically chose products based on specific features such as aesthetics, technical performance, and price. EPDs provide further information for consideration. For instance, in addition to selecting a product based on price, color, and performance, a design professional can also choose the material with the lowest carbon footprint or embodied energy. Using EPDs, some environmental impacts can be compared directly. As discussed, one should consider which impact categories are of greatest interest for each project.

Comparing products without EPDs

In the ideal future, most products will have EPDs. At present, making accurate and meaningful comparisons of similar products can require a fair amount of effort from the stakeholder.

In some situations, there may be one EPD published for a specific product and generic industry data might be available for other products. For instance, in the aforementioned EPD for fly ash brick, a formal LCA was conducted by architecture firm Perkins+Will using Gabi 5.0—software to perform the lifecycle assessments.

There are not yet any EPDs for clay brick (both are in the same product category). However, a generic LCA for clay brick exists in the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) Building for Environmental and Economic Sustainability (BEES) Online database.

The data from the fly ash brick EPD can be compared to the NIST BEES Online data to draw some conclusions. The user needs to research the data to understand boundaries used in the fly ash brick LCA (presented in the EPD) and the clay brick LCA to ensure an accurate comparison is made. In this case, the boundaries and assumptions are the same for both types of bricks through the cradle-to-gate phases, but change in the gate-to-grave phases. Thus, the meaningful comparison is made using cradle-to-gate boundaries. The fly ash brick manufacturer reported environmental impacts by individual lifecycle phase, so determining the cradle-to-gate impact from the EPD is relatively easy.

In other situations, when no (or questionable) lifecycle data is available, it can be worth contacting product manufacturers to ask questions regarding environmental impact. Even a high-level understanding of a manufacturing process can provide some insight into environmental impact. For example, if a product (such as a brick) requires days of high-temperature heat treatment, a user can determine the product likely has a high carbon footprint and embodied energy.

Conclusion

Environmental product declarations and lifecycle assessments are important tools for assessing the environmental impact of materials and associated product selection decisions. LCAs provide design professionals with additional information when choosing among products; they are one more method for weighing the attributes of material selections. As always, design professionals must exercise professional judgment when choosing materials.

Even in the absence of ISO-compliant EPDs or LCAs based on PCRs, it is important to gather environmental data for the products in buildings. Such educated selections are perhaps the best way to avoid ‘greenwashing.’ These selections can also play a significant role in reducing a building’s environmental footprint before a single tenant takes occupancy. Though it can take some effort now, as design professionals increasingly ask for environmental impact information, more will become available. Additionally, as the demand grows for independent, standardized, verified product information, the comparison process will get easier.

Julie Rapoport, PhD, PE, LEED AP, is vice president of engineering at CalStar Products. She has more than a decade of experience in the fields of building technology, concrete products, and cementitious materials. Rapoport earned her PhD at Northwestern University (Evanston, Illinois) and her degrees in physics and English from Williams College (Williamstown, Massachusetts). She can be reached by e-mail at info@calstarproducts.com.