Lessons in adaptive reuse

While the projects by Rockrose, for example, started out with older buildings in Greenwich Village, the firms progressed to proposing much larger projects, such as the West Coast Apartments—an entire block of cold-storage warehouses converted to housing. The initial demonstration projects led to further development in those neighborhoods and influenced other developers in large cities around North America.

Today’s project examples run the gamut from power plants turned into housing and schools that have become healthcare clinics to remote psychiatric hospitals converted to senior housing communities. The emergence of festival marketplaces, such as Boston’s Quincy Market in 1976 by architect Benjamin C. Thompson or San Francisco’s Ferry Building by Page & Turnbull in 2003, illustrated the broad appeal of converting historic buildings to attract throngs of tourists and shoppers. The more recent creative adaptations include hospitals turned into residential spaces and even third uses of structures, such as RKTB’s conversion of a synagogue to an outpatient health clinic and, last year, to a new purpose as a universal pre-kindergarten facility.

Other adaptive reuse opportunities have been born of urban blight and even tragic circumstances. The 1978 Turtle Bay Towers in East Midtown Manhattan, for example, emerged from a 26-story, 1929 loft building that was badly damaged in a gas explosion. The event caused structural damage primarily in the stair towers, although a 15-m (50-ft) wide section of the brick façade extending from street level to the top story was also lost. By cutting away the demolished shafts, RKTB created a courtyard opening up the west wall of apartments to natural light. This modification also decreased the building’s total volume so zoning regulations would allow the lost space to be regained in the form of greenhouse windows installed on the exterior of most upper floors.

With the building transformed into hundreds of luxury rental units, the project’s size and complexity caught the imagination of public and professionals alike. Paul Goldberger, then-architecture critic for The New York Times, noted Turtle Bay Towers “comes closer to the luxury housing of another era than anything that has been built in many years in New York.”

A review in Architectural Record added, “the interiors were designed to capitalize on views, light, and that spatial variety. A total of 341 apartments benefit from the commercial proportion of the building.”

Those apartments offer residents 3.5-m (12-ft) high ceilings and 2.5-m (8-ft) high windows running the width of many of the residences. The project earned an Honor Award from the American Institute of Architects (AIA) and Housing magazine.

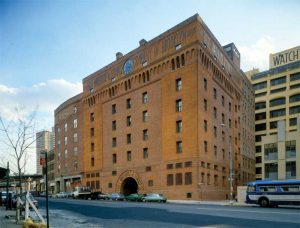

Numerous other adaptive reuse works have also resonated across the country. The 1894 Eagle Warehouse in Brooklyn, New York, for example, was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1974 before being redeveloped and reopened as apartments in 1980. The design by RKTB partner Bernard Rothzeid, FAIA, cost about $3 million including the purchase of the property, helping to demonstrate the economic benefits of adaptive reuse. This and similar projects near the Brooklyn Bridge landing led to a slew of others that repopulated the entire Fulton Landing area and sparked new commercial activity over decades. Warehouses and defunct manufacturing sites became the cornerstones of vibrant neighborhoods.

In recent years, cities with highly regulated development such as San Francisco have been accommodating growth in office and commercial space not with sprawling new buildings and campuses, but with properties one account describes as: right under their noses—in the middle of the city. For years, the office space had been disguised as an auto-body shop, an old Victorian, an empty warehouse, an abandoned office building, or in the case of a SoMa corner, an old church.

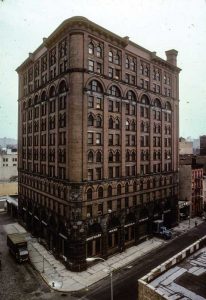

Other projects, such as the conversion of Philadelphia’s 1932 PSFS Building into the Loews Philadelphia Hotel by architects William Lescaze and George Howe, showed how a national historic landmark—and the first U.S. skyscraper in the international style—could be reincarnated as a popular hotel and mixed-use complex.

As seen in these decades of projects, the advantages of conversion approaches include the ability to reuse the basic building shell and potential gains such as increased floor or window area. Specific challenges common to many adaptive reuse projects include meeting the requirements of building codes and standards, incorporating any changes needed to meet use-specific zoning, and making improvements for accessibility, occupant egress, and other life-safety upgrades.

Adaptive reuse considerations

Clearly there is an emotional aspect to saving historic landmarks and buildings that have made essential contributions to a neighborhood or region. On a purely technical level, considerations for evaluating candidates for adaptive reuse also tend to be project specific. Per IEBC, there are three compliance paths for architects to consider in assessing the degree of work required and addressing the “alteration, repair, change of occupancy, addition, or relocation of all existing buildings.” These compliance methods are:

- prescriptive;

- work area; and

- performance.

The prescriptive method is similar to provisions under the International Building Code’s (IBC’s) Chapter 34, “Existing Structures,” which specify structural triggers for any proposed alterations, renovations, or changes of occupancy. The work area method is considered an adaptable compliance option, as specific code provisions are only triggered if the work warrants them. The performance method involves a scoring approach related to the structural and life-safety conditions of the existing building. Low scores indicate building officials and project teams must jointly determine the work required to meet minimum scoring criteria.