Lessons in adaptive reuse

by sadia_badhon | February 1, 2019 11:20 am

by Carmi Bee, FAIA, and Peter Bafitis, AIA

[1]

[1]Adaptive reuse has been a long-term success story in North American cities and former industrial and institutional areas. This process involves maximizing the use of existing buildings and materials and restoring the urban and architectural fabric to revitalize cities and places. Tracing the history of advances through the long account of the adaptive reuse movement offers architects and project teams valuable context and insight into current approaches. These authors have been involved in scores of adaptive reuse projects over the last six decades, some of which help illustrate key methods for successful conversion developments. Wide use of zoning variances, as well as model codes such as the International Existing Building Code (IEBC), provides a sturdy platform for architects and specification writers.

Early influences (such as work by these authors’ firm, RKTB Architects, and others in New York City beginning in the 1970s) helped set the initial directions for converting disused urban manufacturing and warehouse buildings into live-work occupancies. The emergence of more flexible zoning rules, passed in 1967 and expanded in 1977, added new allowances for adaptive reuse of varied building types, including those for the artists in residence (AIR) designation.

The AIR zoning law allowed for the conversion of scores of commercial lofts for residential use as ‘joint living-working’ occupancies, but only if a verified artist lived on the premises. In other words, these properties would be off-limits to noncertified artists. The properties marked AIR were ‘made safe’ for these new uses and signage was posted on the entries of early conversions so firefighters would know the buildings contained residential units and artists’ loft studios.

A few years later, in 1979, the National Endowment for the Arts (NEA) enlisted architect Carmi Bee, FAIA (co-author of this article), to study the emergence of artist live-work spaces in converted structures, including seminal projects such as the 1967 to 1970 Westbeth Artists’ Housing[2]. This project was a complex of massive steel and concrete structures originally owned by Bell Laboratories in New York City’s Greenwich Village, redesigned as residences by Richard Meier & Partners. Bee also studied similar approaches and opportunities for the application of AIR-type conversions in several U.S. cities, including San Francisco, Los Angeles, Chicago, Boston, Seattle, and Portland. The opportunities reported for adaptive reuse were significant, as were the challenges identified for these projects. The findings still resonate today.

Adaptive reuse projects may require:

- modifications for fire and life safety;

- structural retrofits, including for wind and seismic loads;

- energy-related upgrades;

- supplemental accessibility features;

- egress enhancements; and/or

- analysis of fire ratings of archaic materials/assemblies for historic structures.

[3]

[3]Around the same time as the NEA study, new building codes and hybrid zoning designations were being passed in several jurisdictions, including in the East Coast cities of Boston and Philadelphia, in other, older industrial areas in Los Angeles, and later in Seattle. Some of these jurisdictional ordinances share characteristics of the AIR zoning designation seen in Manhattan. For example, mandatory requirements for components such as a rear yard were waived, as were minimum window sizes for daylight and air for these types of adaptations to residential occupancies. Along with the loosening of such key restrictions on the gainful reuse of old cast-iron and masonry buildings covering thousands of properties, these new rules allowed owners to apply for certificates of occupancy in properties that would previously be considered illegal or in violation of codes.

Savvy real estate developers saw the opportunity to unlock and capture the value of older buildings. Many of the existing manufacturing and warehouse structures were built larger than would be allowed under more recently adopted zoning, so these entrepreneurial builders also enlisted engineers and architects who verified the basic bones of the buildings—their structural systems, floors, walls, stairs, and other elements—were often built well and could be adapted both cost-effectively and safely.

Some preservationists also liked the approach, as it protected the historic urban fabric that had come to define certain city neighborhoods. Over time, advocates for sustainable design and urban revitalization quantified the benefits to their regions of this environment of ‘recycling history’ for new uses. In fact, the embodied energy of the structures saved and converted in adaptive reuse projects is the equivalent of billions of tons of carbon dioxide (CO2), according to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). Considering that material consumption creates about 41 percent of CO2 emissions and the main source of human toxicity is new building construction, per EPA, it seems important to continue supporting adaptive reuse[4].

Recent and seminal reuse projects

Prior to groups like the Rouse Companies (known since the late 1970s for creating European-style festival marketplaces in large converted historic structures), young developers such as Rockrose Development Corp., founded in 1970, formed with a specific interest in revitalizing neighborhoods and creating new attainable housing options in areas where they were sorely needed. An essential part of the business approach of these new real estate companies was leveraging shifts in zoning and building codes, including the AIR rules and other regulations allowing conversions of intended use, relaxed environmental rules, or the renovation of historic landmarks.

[5]

[5]While the projects by Rockrose, for example, started out with older buildings in Greenwich Village, the firms progressed to proposing much larger projects, such as the West Coast Apartments—an entire block of cold-storage warehouses converted to housing. The initial demonstration projects led to further development in those neighborhoods and influenced other developers in large cities around North America.

Today’s project examples run the gamut from power plants turned into housing and schools that have become healthcare clinics to remote psychiatric hospitals converted to senior housing communities. The emergence of festival marketplaces, such as Boston’s Quincy Market in 1976 by architect Benjamin C. Thompson or San Francisco’s Ferry Building by Page & Turnbull in 2003, illustrated the broad appeal of converting historic buildings to attract throngs of tourists and shoppers. The more recent creative adaptations include hospitals turned into residential spaces and even third uses of structures, such as RKTB’s conversion of a synagogue to an outpatient health clinic and, last year, to a new purpose as a universal pre-kindergarten facility.

Other adaptive reuse opportunities have been born of urban blight and even tragic circumstances. The 1978 Turtle Bay Towers in East Midtown Manhattan, for example, emerged from a 26-story, 1929 loft building that was badly damaged in a gas explosion. The event caused structural damage primarily in the stair towers, although a 15-m (50-ft) wide section of the brick façade extending from street level to the top story was also lost. By cutting away the demolished shafts, RKTB created a courtyard opening up the west wall of apartments to natural light. This modification also decreased the building’s total volume so zoning regulations would allow the lost space to be regained in the form of greenhouse windows installed on the exterior of most upper floors.

With the building transformed into hundreds of luxury rental units, the project’s size and complexity caught the imagination of public and professionals alike. Paul Goldberger, then-architecture critic for The New York Times, noted Turtle Bay Towers “comes closer to the luxury housing of another era than anything that has been built in many years in New York.”

A review in Architectural Record added, “the interiors were designed to capitalize on views, light, and that spatial variety. A total of 341 apartments benefit from the commercial proportion of the building.”

Those apartments offer residents 3.5-m (12-ft) high ceilings and 2.5-m (8-ft) high windows running the width of many of the residences. The project earned an Honor Award from the American Institute of Architects (AIA) and Housing magazine.

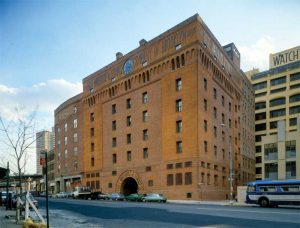

Numerous other adaptive reuse works have also resonated across the country. The 1894 Eagle Warehouse in Brooklyn, New York, for example, was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1974 before being redeveloped and reopened as apartments in 1980. The design by RKTB partner Bernard Rothzeid, FAIA, cost about $3 million including the purchase of the property, helping to demonstrate the economic benefits of adaptive reuse. This and similar projects near the Brooklyn Bridge landing led to a slew of others that repopulated the entire Fulton Landing area and sparked new commercial activity over decades. Warehouses and defunct manufacturing sites became the cornerstones of vibrant neighborhoods.

In recent years, cities with highly regulated development such as San Francisco have been accommodating growth in office and commercial space not with sprawling new buildings and campuses, but with properties one account describes as: right under their noses—in the middle of the city. For years, the office space[6] had been disguised as an auto-body shop, an old Victorian, an empty warehouse, an abandoned office building, or in the case of a SoMa corner, an old church.

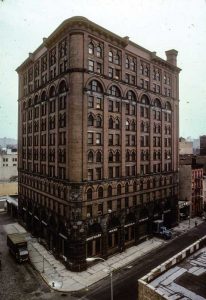

Other projects, such as the conversion of Philadelphia’s 1932 PSFS Building into the Loews Philadelphia Hotel by architects William Lescaze and George Howe, showed how a national historic landmark—and the first U.S. skyscraper in the international style—could be reincarnated as a popular hotel and mixed-use complex.

[7]

[7]As seen in these decades of projects, the advantages of conversion approaches include the ability to reuse the basic building shell and potential gains such as increased floor or window area. Specific challenges common to many adaptive reuse projects include meeting the requirements of building codes and standards, incorporating any changes needed to meet use-specific zoning, and making improvements for accessibility, occupant egress, and other life-safety upgrades.

Adaptive reuse considerations

Clearly there is an emotional aspect to saving historic landmarks and buildings that have made essential contributions to a neighborhood or region. On a purely technical level, considerations for evaluating candidates for adaptive reuse also tend to be project specific. Per IEBC, there are three compliance paths for architects to consider in assessing the degree of work required and addressing the “alteration, repair, change of occupancy, addition, or relocation of all existing buildings.” These compliance methods are:

- prescriptive;

- work area; and

- performance.

The prescriptive method is similar to provisions under the International Building Code’s (IBC’s) Chapter 34, “Existing Structures,” which specify structural triggers for any proposed alterations, renovations, or changes of occupancy. The work area method is considered an adaptable compliance option, as specific code provisions are only triggered if the work warrants them. The performance method involves a scoring approach related to the structural and life-safety conditions of the existing building. Low scores indicate building officials and project teams must jointly determine the work required to meet minimum scoring criteria.

[8]

[8]By their very nature, adaptive reuse projects challenge architects and specifiers, who typically cannot know all the work requirements and building conditions up front. In many cases, the design team learns as the demolition and adaptation work progresses. This brings an improvisational aspect to the design process, according to architects experienced in adaptive reuse. Additionally, some ‘grandfathering’ of existing conditions may be allowed.

“Under limited circumstances, a building alteration can be made to comply with the laws under which the building was originally built,” according to IEBC, “as long as there has been no substantial structural damage and there will be limited structural alteration.”

Further complicating the picture, some building repairs can use materials and methods like those of the original construction, while other repairs must comply with requirements for new buildings. IEBC describes three levels of alterations to existing buildings per the work area compliance method:

- Level 1, covering only replacement of building components with new materials;

- Level 2, including space reconfiguration; and

- Level 3, referring to extensive space reconfiguration exceeding 50 percent of the building area.

There are numerous typical scopes of work of which one should be aware.

Structural systems

Addressing the structural challenges of existing buildings can range from straightforward to extensive and invasive. Adaptive reuse projects may include requirements for seismic and wind retrofits to meet modern standards, which may be complicated to achieve in historic buildings.

“While many jurisdictions have adopted prescriptive standards, primarily for certain building types such as unreinforced masonry loadbearing walls, more sophisticated, performance-based evaluation methods allowed by some codes offer more flexibility,” says the National Park Service[9] (NPS).

Mechanical, electrical, and plumbing systems

[10]

[10]Designing improvements for existing and new mechanical, electrical, and plumbing (MEP) systems are challenging due to “many unknowns. Are there looming issues in the ceiling or behind a wall that cannot be accessed during our design survey?” asks Dewberry engineer Nicholas Saponara, PE.

Saponara adds the design basis should “determine building engineering tolerances and establish what is needed to maintain a minimum function of the building.”

Energy-efficiency codes, including mandates or incentives for conservation measures, also impact adaptive reuse. For example, the New York City Department of City Planning’s (DCP’s) Zone Green initiative allows for adding external thermal insulation to building walls without incurring floor-area penalties. Such incentives can increase flexibility for adding sun-control devices and rooftop additions such as solar hot water and green roofs.

Just as important as operational efficiency, experts contend, are the savings in embodied energy represented by adaptive reuse projects. Conversion of building use is an energy-saving methodology and one of its benefits is embodied energy and cost reductions provided by adapting and recycling the structure rather than building new.

Accessibility and supplemental accessibility

In any conversion of use, the main consideration for architects is applying current codes and zoning, including local accessibility rules and the 2010 Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA). In general, supplemental accessibility is widely mandated except in relatively rare cases due to compelling public interest. NPS describes “the need to balance accessibility and historic preservation,” and recommends a three-step approach for implementing accessibility[11] modifications that protect the integrity of a property’s “character-defining features.”

These steps are:

- to review the historical significance of the property and identify its character-defining features;

- to analyze the existing levels of accessibility versus those required; and

- develop and compare viable accessibility options within a preservation context.

For nonhistoric buildings, ADA rules generally strictly apply. Additionally, IEBC requires alterations made to the areas of primary function must comply with current code and have accessible routes that are also code compliant. There may be exceptions, however, including the ‘20 percent rule[12],’ which says that the costs of providing the accessible route[13] are not required to exceed 20 percent of the costs of the alterations affecting the area of primary function.

[14]

[14]Fire- and life-safety issues

Protecting human safety is paramount in all projects, and in adaptive reuse there are special considerations for fire safety. Among these is the requirement in local codes and IEBC in most jurisdictions in order to determine the fire ratings of “archaic materials and assemblies[15].” The definition of ‘archaic’ generally alludes to construction completed prior to 1950, and the performance of these building elements is defined according to hours of fire resistance (for walls and shaft enclosures, for example) and by measures such flame spread, smoke production, and degree of combustibility. Since documentation of fire performance is not readily available for many assemblies, a mix of engineering judgment, testing, and remediation may be needed to resolve the concerns of building officials.

Case studies of adaptive reuse

The addition of new fixtures and modern amenities to existing buildings is common in adaptive reuse projects. A number of valuable case studies show how building owners and design teams can rise to the challenges of these projects and not only meet the minimum codes, but also exceed the market’s offerings in unique ways to create landmarks in their communities.

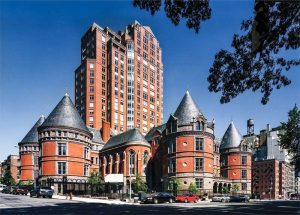

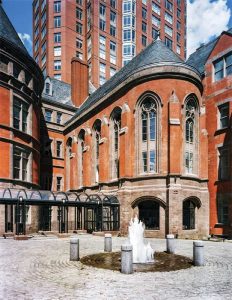

One example is the conversion of an 1884 building: the first U.S. hospital dedicated to the then-emergent field of cancer treatment, located at 455 Central Park West in New York City and is distinguished by majestic turrets and a chapel. This project is the winner of several awards, including the 2005 Lucy G. Moses Preservation Award from the New York Landmarks Conservancy, the Best of 2004 Annual Award, and the Gold Award for Engineering Excellence from the American Consulting Engineers Council (ACEC). This 100-unit luxury condominium complex combines the building, designed by Charles Coolidge Haight and listed on the National Register of Historic Places, with a newly added, 27-story residential tower overlooking the park.

The original building was converted to a nursing home in 1956 and eventually vacated in the early 1970s. Over time, the once-majestic structure fell into an advanced state of decay: stonework was displaced or eroded and its distinctive wood and slate roof became unsalvageable. Most of the windows and trim were missing and inside the structure, all the original finishes and most of the floor had been lost or damaged. In 2001—after years of design study, public approvals, and construction bidding—a comprehensive restoration of the exterior and gut renovation of the interior commenced. This included a full replacement of the roof.

As with many historic adaptive reuse projects, careful research and forensic analysis were required to determine the safety and suitability of various archaic material assemblies. Months of meticulous surveying led to the cataloguing and storage of many architectural features to be reinstalled or replicated as part of the project. A detailed evaluation of window materials and alternatives that was undertaken for the city’s Landmarks Preservation Commission (LPC) led to solutions for combining historic fabric with lasting, attractive replacements. Within the existing shell, the project team inserted an entirely new concrete structure, and new residential layouts take advantage of the landmark’s unique original geometries. The richly proportioned spaces found within the former hospital facilitated the creation of luxurious and highly marketable apartments, with interiors restored to the gracious opulence of the turn of the century.

455 Central Park West goes far beyond a conventional restoration. It took almost 25 years to be realized and demonstrates how extremely challenging an adaptive reuse project can be while still resulting in an unforgettable place with some of the most valuable residences in a major metropolitan area. In this way, adaptive reuse proves its worth, not only serving to restore significant historic places to their previous splendor, but also acting as a catalyst for the revitalization of surrounding neighborhoods and cities.

- [Image]: https://www.constructionspecifier.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/455-CPW-Exterior-SE-View_Bartelstone.jpg

- Westbeth Artists’ Housing: http://www.richardmeier.com/%20?projects=westbeth-artists-housing-2

- [Image]: https://www.constructionspecifier.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/455-CPW-Entry-Court_Bartelstone.jpg

- supporting adaptive reuse: http://www.sustainablecitynetwork.com/%20topic_channels/building_housing/article_951afefa-ffb3-11e2-b3cb-001a4bcf6878.html

- [Image]: https://www.constructionspecifier.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/Eagle-Warehouse-Exterior_RKTB.jpg

- space: http://www.nps.gov/tps/how-to-preserve/briefs/32-accessibility.htm

- [Image]: https://www.constructionspecifier.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/Shephard-House-Before_RKTB.jpg

- [Image]: https://www.constructionspecifier.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/Shephard-House-After_RKTB.jpg

- National Park Service: http://www.nps.gov/tps/how-to-%20preserve/briefs/41-seismic-rehabilitation.htm

- [Image]: https://www.constructionspecifier.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/K491-71st-St-UPK-Classroom_RKTB.jpg

- accessibility: http://www.nps.gov/tps/how-to-preserve/briefs/32-accessibility.htm

- 20 percent rule: http://www.iccsafe.org/forum/non-structural-intl-bldg-residl-codes/iebc-605-2-accessible-route-20-rule

- accessible route: http://www.adasearch.info/srp/Title3Regs.php

- [Image]: https://www.constructionspecifier.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/K491-71st-St-UPK-FINAL.jpg

- archaic materials and assemblies: http://up.codes/viewer/pennsylvania/iebc-2009/chapter/resource_A1/fire-related-performance-of-archaic-materials-and-assemblies#resource_A1

- cbee@rktb.com: mailto:cbee@rktb.com

- pbafitis@rktb.com: mailto:pbafitis@rktb.com

Source URL: https://www.constructionspecifier.com/lessons-in-adaptive-reuse/