Making the air barrier argument for tilt-up

Photo courtesy Powers Brown Architecture

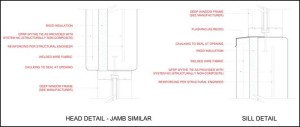

Details on delivering the air barrier are established in the sub-sections C402.4.1.1 (“Air Barrier Construction”) and C402.1.2 (“Air Barrier Compliance Options”). The air barrier must be continuous for all assemblies that are the thermal envelope of the building (and across the joints and assemblies). Further, air barrier joints and seams must be sealed, including sealing transitions in places and changes in materials.

Air barrier penetrations have to be sealed in accordance with Section C402.4.2. The joints and seals shall be securely installed in or on the joint for its entire length so as not to dislodge, loosen, or otherwise impair its ability to resist positive and negative pressure from wind, stack effect, and mechanical ventilation.

“The significance of this section for tilt-up construction,” says Baty, “is tilt-up as a mature process already delivers both of these components 100 percent of the time. The panels themselves are constructed of a material component qualified by C402.4.1.2 as a rated air barrier—concrete—and the individual panels are sealed to form a continuous building envelope at every joint with a high-performance caulking system on both the interior and exterior. Additionally, details incorporating the wall systems with the roof assembly maintain continuity from concrete to roof membrane with several standard details and approved methods.”

Referring to C402.4.1.2.1 for the air barrier compliance options, Baty points out the code states:

Materials with an air permeability no greater than [0.02 L/s • m2] 0.004 cfm/sf under a pressure differential of [75 Pa] 0.3 inches water gauge (w.g.) when tested in accordance with ASTM E2178 [Standard Test Method for Air Permeance of Building Materials] shall comply with this section.

Cast-in-place and precast concrete—the embodiment of tilt-up—are both listed as “acceptable” or “approved” materials under this section. Additionally, many modern tilt-up wall systems are energy-efficient insulated sandwich panels consisting of two layers of such concrete and a continuous layer of rigid insulation, also listed as an “acceptable” or “approved” material.

There are many options to consider and, as the air barrier section continues, more complex envelope assemblies can deliver the required performance. However, as Baty notes, this also means higher considerations for construction quality supervision and more extensive material selection and integration.

Section C402.4.1.2.2 of the 2012 IECC states:

Assemblies of materials and components with an average air leakage not to exceed [0.2 L/s • m2] 0.04 cfm/sf under a pressure differential of [75 Pa] 0.3 inches of water gauge (w.g.), when tested in accordance with ASTM E2357 [Standard Test Method for Determining Air Leakage of Air Barrier Assemblies], ASTM E1677 [Standard Specification for Air Barrier Material or System for Low-rise Framed Building Walls], or ASTM E283 [Standard Test Method for Determining Rate of Air Leakage Through Exterior Windows, Curtain Walls, and Doors Under Specified Pressure Differences Across the Specimen], shall comply with this section. Assemblies listed in Items 1 and 2 shall be deemed to comply provided joints are sealed and requirements of Section C402.4.1.1 are met.

Other examples given in this section include:

- concrete masonry unit (CMU) walls that must be coated with one application either of block filler and two applications of a paint or sealer coating; or

- a portland cement/sand parge, stucco, or plaster of a minimum 12 mm (1/2 in.) thickness.

These systems add significant cost to the traditional methods. Also, the code does not limit itself to the building envelope assembly. Ensuring the designed performance is a requirement, as IECC states in C402.4.1.2.3:

Image courtesy Thermomass

The completed building shall be tested and the air leakage rate of the building envelope shall not exceed 0.40 cfm/sf at a pressure differential of [2.0 L/s • m2 at 75 Pa] 0.3 inches water gauge in accordance with ASTM E779 [Standard Test Method for Determining Air Leakage Rate by Fan Pressurization] or an equivalent method approved by the code official.

The advantage in this knowledge is, according to the code, even a tilt-up building is not just an opaque building envelope, but rather an assembly including windows and doors. This means tests will likely still be required for the composite envelope assembly. However, with the simplicity of satisfying core requirements for materials and assemblies for air barrier performance, the project team can feel much more at ease with the pending outcome of the test.