Managing moisture without sacrificing breathability

by Samantha Ashenhurst | August 15, 2018 2:38 pm

[1]

[1]by Bijan Mansouri

In the building industry’s ever increasing pursuit of tighter and more waterproof structures, is there a point at which a wall is built too tight? While a watertight assembly is vitally important for wall controlling issues such as mold growth and protecting indoor air quality (IAQ), some building practices may be inadvertently making it easier for moisture-related issues to fester. After all, no matter how tightly a wall is constructed, water is inevitably going to find its way in. There is no such thing as a “waterproof” wall, just one built so tightly it is almost guaranteed to get and stay wet.

The highest performing wall assemblies are the ones designed to realistically manage moisture and dry out, and not those designed with the unachievable goal of completely locking out all moisture. The good news is there are a growing number of methods for managing moisture, driven by advances in material technology, evolving building codes, and a growing awareness among end-users for mold prevention, IAQ, and energy efficiency.

Finding the “sweet spot” for material permeability

Water can find its way into a wall in numerous ways. High humidity and extreme temperatures can cause vapor diffusion when warm, indoor air causes condensation on colder, outside surfaces. Wind-driven rain can be forced into small openings in the exterior cladding at joints, laps, and utility cutouts, and wind blowing around the building can create a negative pressure within the wall assembly, which siphons water into the wall.

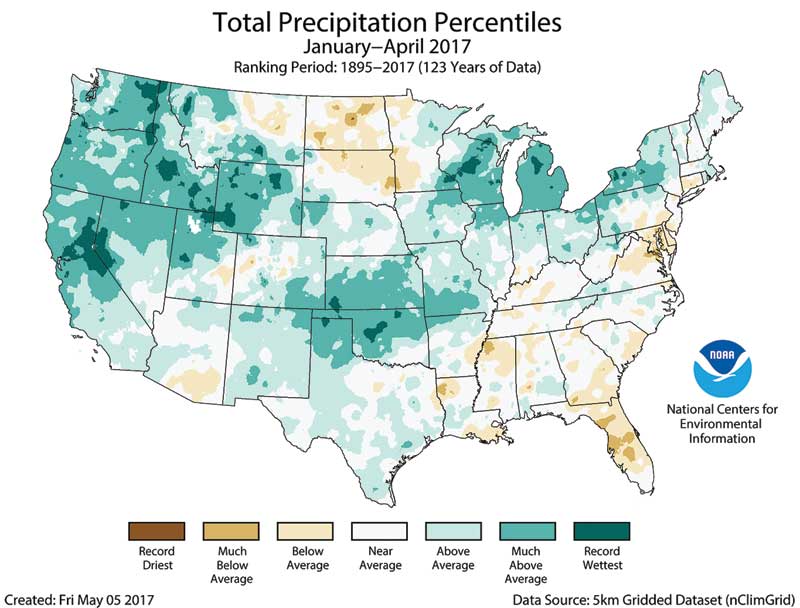

One of the most challenging situations in which to manage moisture is when a reservoir cladding like fiber cement, brick, or stone is specified in a region where air-conditioning is often used and with an annual rainfall of 508 mm (20 in.) or more. Most of the country falls within these conditions, and a growing preference for reservoir claddings require more careful attention to managing moisture.

When reservoir claddings become wet from rainwater or condensation and are then warmed by the sun, the vapor pressure of the stored water increases, driving it both inward and outward from the cladding material. Where the moisture goes from there—and how quickly it gets there—is largely a function of the permeability of the adjacent building materials within the assembly.

Permeability measures the amount of vapor transmission a building material will allow over a period of time. ASTM E96, Standard Test Methods for Water Vapor Transmission of Materials, addresses two testing procedures for measuring permeability—the desiccant method and the water method.

In the desiccant method, the material to be tested is sealed to a test dish containing a desiccant, or drying agent, and the assembly is placed in a controlled atmosphere. Periodic weighing determines the rate at which water vapor has moved through the specimen into the desiccant. In the water method, the dish contains distilled water, and periodic weighing determines the rate of vapor movement through the specimen from the water.

In most wall assemblies, outwardly driven moisture will not cause many problems (unless one is dealing with a material like stucco painted with a low-perm paint, in which case bubbling and cracking would be visible). However, the inwardly driven moisture presents a problem, especially in situations where conditioned indoor air is much cooler than the warm, moist exterior.

Typically, this inwardly driven moisture vapor is managed by separating the cladding from the rest of the assembly with a capillary break, which can be a gap or a sheathing material able to shed water or not absorb or pass water. Impermeable sheathing, such as extruded polystyrene (XPS), is one option for halting inward vapor drive. In these types of assemblies, the inwardly driven moisture condenses on the surface of the XPS sheathing and drains downward.

However, in situations where a reservoir cladding is paired with a highly permeable sheathing like gypsum board (which can be as high as 50 perms) or a moisture-retentive material like oriented strand board (OSB), an air gap may not be enough to slow down inward moisture intrusion. In these applications, an added weather-resistant barrier (WRB)—commonly referred to as a building or house wrap—is needed to reduce unwanted moisture intrusion.

In the paper, “Inward Drive – Outward Drying,” building scientist Joseph Lstiburek identifies the “sweet spot” for the permeance of this WRB layer as between 10 and 20 perms. (For more, click here[2].) Too high, he writes, and the moisture driven out of the back side of the reservoir cladding into the air space will blow through the layer and the permeable sheathing and into the wall cavity. Too low, and the outward drying potential of the cavity is compromised. Thankfully, advances in building wrap technology are adapting to meet this need.

[3]

[3]Evaluating WRBs

Plastic building wraps made of polyethylene or polypropylene fabric have been a popular method of protecting against moisture intrusion since the 1970s because of their durability and ease of installation. Since building assemblies have gotten tighter, building wraps have taken on a new function—helping to remove trapped water from the building enclosure. Their unique functionality enables them to both block moisture from the outside while also allowing walls to “breathe” to prevent vapor buildup. The latest innovations in building wrap technology are taking this moisture removal function one step further to incorporate drainage capabilities as well.

The 2018 International Building Code (IBC), Section 1402.2, “Weather Protection,” requires exterior walls “provide the building with a weather-resistant exterior wall envelope…designed and constructed in such a manner as to prevent the accumulation of water within the wall assembly by providing a water-resistive barrier behind the exterior veneer…and a means for draining water that enters the assembly to the exterior.”

This water-resistive barrier, as defined by Section 1403.2, “Weather Protection,” comprises at least “one layer of No. 15 asphalt felt, complying with ASTM D226, Standard Specification for Asphalt-Saturated Organic Felt Used in Roofing and Waterproofing, for Type 1 felt or other approved materials…attached to the studs or sheathing.”

It is important to note the difference between a weather-resistant barrier and a water-resistant barrier, as they have distinct purposes but are often confused with one another. The American Architectural Manufacturers Association (AAMA) defines WRBs as a surface or a wall responsible for preventing air and water infiltration to the building interior. The differentiating factor is a WRB must also prevent air infiltration, while water-resistant barriers are only responsible for stopping water intrusion.

WRBs are commonly specified for commercial buildings or projects where a higher level of performance is desired of the vertical building enclosure and when it is critical to have greater control of interior environmental conditions. Water-resistant barriers, on the other hand, are usually limited to residential and low-rise structures.

The International Code Council-Evaluation Service (ICC-ES) evaluates the following key performance characteristics for building wrap. These characteristics provide a valuable starting point for deciding which product best suits a specific project.

Water resistance

As its most basic function, a building wrap must hold out liquid water. A building wrap should be able to pass both “water ponding” tests, which measure a house wrap’s resistance to a pond of 25 mm (1 in.) water over two hours, and a more stringent hydrostatic pressure test where the wrap is subjected to a pressurized column of water for five hours.

Air resistance

According to the Air Barrier Association of America (ABAA), an air barrier is a system of assemblies within the building enclosure—designed, installed, and integrated in such a manner as to stop the uncontrolled flow of air into and out of the enclosure. Since an air barrier isolates the indoor environment, it plays a major role in the overall energy efficiency, comfort, and IAQ of a building. According to the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE), up to 40 percent of the energy used to heat and cool a building is due to uncontrolled air leakage. As such, the American National Standards Institute/American Society of Heating, Refrigerating and Air-Conditioning Engineers/Illuminating Engineering Society (ANSI/ASHRAE/IES) 90.1-2016, Energy Standard for Buildings Except Low-Rise Residential Buildings, and the International Energy Conservation Code (IECC) include air barrier requirements.

For an individual building material to be classified as an air barrier, its air permeance must be equal to or less than 0.02 L/(s-m2) @ 75 Pa when tested in accordance with ASTM E2178, Standard Test Method for Air Permeance of Building Materials. However, this air permeance test only measures the amount of air migrating through the material itself and not through holes or gaps in the larger assembly. Therefore, it is important to keep in mind a material’s effectiveness as an air barrier is largely dependent on proper installation and the use of compatible tapes, fasteners, and sealants.

[4]

[4]Durability

The ICC-ES looks at the tear resistance and tensile strength as the best measure of a building wrap’s durability, since it must be able to withstand the handling and application process without compromising its water resistance. Ultra violet- (UV) and low-temperature resistance are also important measures of durability because prolonged exposure to the elements can compromise the integrity of the product or cause it to crack.

Vapor permeability

For a product to be considered a building wrap and not a vapor retarder, ICC-ES mandates the permeance rating must be higher than 5 perms. However, permeability is achieved in a variety of ways, and as noted by Lstiburek, a higher perm rating does not always equal a better building wrap.

When selecting a building wrap, look for one that hits the “sweet spot” of 10 to 20 perms to achieve the desired balance of moisture protection and drying capacity. For example, some wraps have mechanical micro-perforations, which may allow the passage of more water vapor, but could also be more vulnerable to bulk water leakage. Generally, it is better to go with a higher quality, non-perforated or micro-porous product allowing for sufficient vapor mitigation while providing excellent resistance to bulk water.

Drainage

Drainage is widely accepted as one of the most effective measures for reducing moisture damage due to rain penetration. Drainage is a critical component in allowing a building wrap to do its job, particularly in keeping walls dry. Usually, this involves the use of furring strips separating the wrap from the structural sheathing and framing, but emerging technologies are helping to simplify this process.

Building wrap manufacturers have developed new products integrating drainage gaps into the material itself through creping, embossing, weaving, or filament spacers. These new technologies eliminate the need for furring strips as a capillary break, helping to reduce material costs and streamline installation.

These drainable building wraps meet all current standards for drainage efficiency (ASTM E2273) and are also vapor permeable, helping to address many of the moisture management issues described earlier.

Flammability

When designing wall assemblies, considerations should also be taken to ensure the wall system meets all applicable fire codes. The National Fire Protection (NFPA) 285, Standard Fire Test Method for Evaluation of Fire Propagation Characteristics of Exterior Non-Load-Bearing Wall Assemblies Containing Combustible Components, is the standardized procedure for fire testing of overall exterior wall assemblies when combustible materials, such as foam plastic continuous insulation (ci), panels, and water-resistive barriers, are components within the wall assembly. NFPA 285 is an assembly test, meaning all components of the wall system must be tested together. IBC, generally, requires NFPA 285 testing for exterior wall assemblies with combustible materials on buildings more than 12 m (40 ft) tall.

In addition to the NFPA 285 wall assembly test, relevant combustible components must also pass a series of material tests, per IBC. ASTM E84, Surface Burning Characteristics, comparatively measures product surface flame spread and smoke density. Products are then classified as A, B, or C based on their flame spread index, with Class A offering the lowest flame spread levels. It is important to note this test does not measure heat transmission, determine an assembly’s flame spread behavior, or classify a material as noncombustible. Specifiers should also request ICC-ES reporting data as part of their evaluation to ensure products meet the necessary standards.

[5]

[5]Other variables

Outside of the aforementioned evaluation criteria, specifiers must consider a number of other variables when selecting a WRB.

Cladding

In addition to the challenges associated with reservoir claddings, other types of cladding require careful consideration when it comes to managing moisture. For example, tightly fastened cladding such as cedar siding or fiber cement board might allow water trapped between the siding and a smooth building wrap to pool and could make its way through the wrap and into the framing. These are cases where a drainable building wrap would provide the needed capillary break to allow water to drain out of the assembly.

Surfactant resistance

The water resistance of a building wrap can be degraded by chemicals known as surfactants (or surface active agents), often found in cladding materials such as cedar and stucco and also in solutions used to power wash siding. These chemicals reduce the surface tension of water, easing its ability to pass through microscopic openings in the membrane. Some building wraps offer added protection against the harmful effects of these chemicals, which might be an important consideration for assemblies constructed using these materials.

Geography and climate

As stated, IBC now mandates an exterior wall assembly incorporate “a means for draining water that enters the assembly to the exterior.” However, a growing number of states have added even more prescriptive measures to their codes. Oregon, for example, now requires “…the [building] envelope shall consist of an exterior veneer, a water-resistive barrier (housewrap, building paper, etc.) and a minimum 1⁄8-in. [3-mm] space between the WRB and the exterior veneer.”

As a rule of thumb, the Building Enclosure Moisture Management Institute (BEMMI) recommends any area receiving more than 508 mm (20 in.) of annual rainfall should incorporate enhanced drainage techniques in the wall system, especially if using an absorptive cladding material. Areas receiving 1016 mm (40 in.) or more should utilize rainscreen design regardless of cladding material. The orientation of the wall, amount of overhang, altitude, and even nearby trees can have an impact on how much water intrusion can be expected and how likely it is to dry.

Taking a system approach

A WRB material alone—no matter how advanced it is—cannot be counted on to protect a structure from unwanted air and moisture movement without taking the whole assembly into consideration. It is important to specify compatible materials to ensure all components work together.

For example, sealants with high solvent or plasticizer content can damage bitumen flashing products causing functional and aesthetic issues. When seams and tears are not properly taped, they allow windblown rain to infiltrate the assembly. Failure to use galvanized roofing nails or plastic cap nails to attach the WRB to the sheathing and framing can also compromise performance.

To counter this problem, some manufacturers have developed a system approach including compatible tapes for seaming and adhesive flashings for openings. When installed together, these systems are often assured through extended warranties from the manufacturer. When in doubt, always check the manufacturer’s website for additional guidance.

Changing building codes and greater adoption of certain cladding materials have caused specifiers to take a closer look at how moisture is managed in the wall assembly. Advances in building wrap products have added a powerful tool to help achieve these goals. The smart way forward is to avoid waterproofing the wall to the detriment of breathability, but to rather take a holistic approach to designing a wall system providing adequate protection against water but also able to dry out when it inevitably gets wet.

Bijan Mansouri is the technical manager at Typar Construction Products. He has been with Berry Plastics for 25 years, working in different technical capacities. Mansouri is responsible for building code requirements, design and development of new construction products, and education on proper practice and installation of building envelope. He received his bachelor’s and master’s degrees in mechanical/aerospace engineering, and is a member of the Air Barrier Association of America (ABAA) and ASTM. He can be reached at bijanmansouri@berryglobal.com[6].

- [Image]: https://www.constructionspecifier.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/08/DSC_2179_retouched_5x7.jpg

- here: https://buildingscience.com/documents/building-science-insights/bsi-061-inward-drive-outward-drying

- [Image]: https://www.constructionspecifier.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/08/january-april-2017-us-total-precipitation-percentiles-map.jpg

- [Image]: https://www.constructionspecifier.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/08/FlashingAroundAWindow.jpg

- [Image]: https://www.constructionspecifier.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/08/TYPAR_DRAINABLEWRAP_4X4.jpg

- bijanmansouri@berryglobal.com: mailto:bijanmansouri@berryglobal.com

Source URL: https://www.constructionspecifier.com/managing-moisture-without-sacrificing-breathability/