Photo courtesy Cooper Robertson

Color temperature

Color temperature is a description of the warmth or coolness of a light source. LED sources now allow for a fuller color spectrum, which renders museum objects accurately by the standards of many major institutions. LEDs are also available with a warm color spectrum particularly similar to that of halogen lamps. It is crucial to obtain LEDs from manufacturers with very tight control over consistency, since even LEDs with the same color temperature from the same manufacturer can look different. This is particularly the case with white sources. (For more, read Brian Stacy, Matt Franks, and Andrew Sedgwick’s “Gallery Electric Lighting Report” from Ove Arup & Partners, New York, published in November 2010.)

Color rendering

The color rendering index (CRI) of a light source is a quantitative measure of its ability to reproduce the colors of objects faithfully compared to illumination by natural light. This may be the most significant factor to consider for gallery use, but maintaining a consistent color rendering has been a major challenge for lighting manufacturers. (Read “LED Lighting Overview and Opportunities” from Ove Arup & Partners, New York, published in November 2010.)

Cost and energy savings

Energy savings from LED lamps can be significant compared to those halogen offers. Maintenance costs may also be reduced, since the long lamp life of LEDs significantly reduces the replacement cycle duration of traditional lamps. This means maintenance needs may also be reduced in conditions where access

to lighting systems is difficult, such as in remote or very high locations. Limiting the hours required for skilled labor in hard-to-reach locations is a significant benefit.

On new projects, the higher initial cost of LED lighting systems may be offset by reducing overall lighting loads and thus the size of new building mechanical systems. Many major existing institutions, including the Smithsonian, Getty, and Metropolitan museums, have studied and begun to implement LED lighting in at least a portion of their galleries, while other new institutions (including the Whitney) have installed full LED systems in all galleries.

Conclusion

The Whitney’s design demonstrates how a contemporary museum can accommodate daylight and views with flexibility and without compromising the conservation requirements of the art. The benefits of this approach are clear—a distinct and varied visitor experience using increased exterior transparency as inspiration for visitors and living artists, engaging the city beyond as an added layer in the curatorial narrative. Through the use of shading technology, LEDs, and innovative daylighting, the Whitney is a museum fully connected to its urban backdrop.

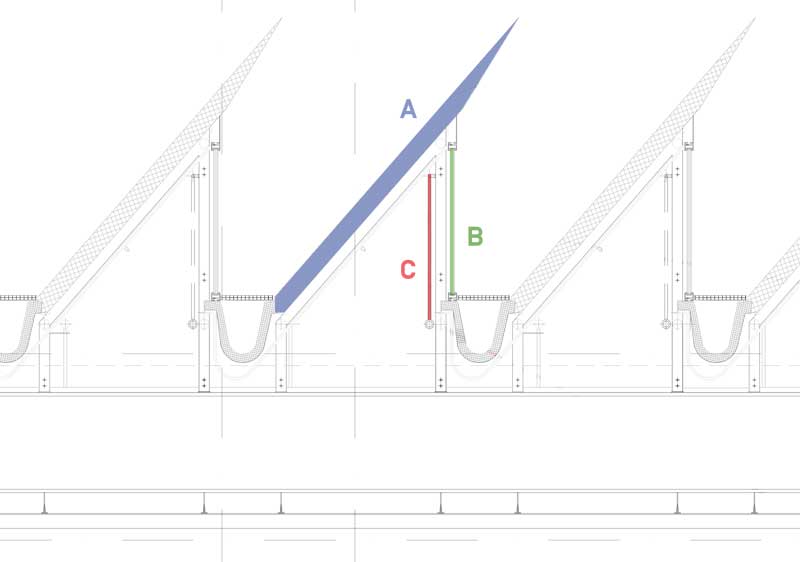

| COMPOSITION OF A SKYLIGHT ROOF |

The Whitney’s clerestory roof has the following components: 1. Inclined roof panels forming a sawtooth light system. These clerestories are opened to the north, and they prevent direct sunlight from passing into the gallery space for most of the year, while also allowing reflected and diffused sunlight to enter. The exterior surface of the inclined roof panels has a neutral matte finish to prevent specular reflections from sunlight. 2. Low-iron insulated glazing units (IGU) with laminated inner lites, providing ultraviolet (UV) filtration. Low-iron glass is used to maximize color rendering, along with low-emissivity (low-e) coatings, which have low heat-transfer properties and offer high light transmission. 3. Motorized roller shades in a bottom-up configuration. These are used to reduce daylight exposure outside the museum’s open hours, block direct early morning and late afternoon sun, and regulate daylight transmission during open hours by variable deployment of the roller shades. |

Scott Newman, FAIA, leads the cultural practice at Cooper Robertson. He has nearly 40 years of experience in the planning and design of complex museums, and was partner-in-charge of the new Whitney Museum of American Art. Newman can be reached via e-mail at snewman@cooperrobertson.com.