FAILURES

FAILURES

Deborah Slaton, David S. Patterson, AIA, and Jeffrey N. Sutterlin, PE

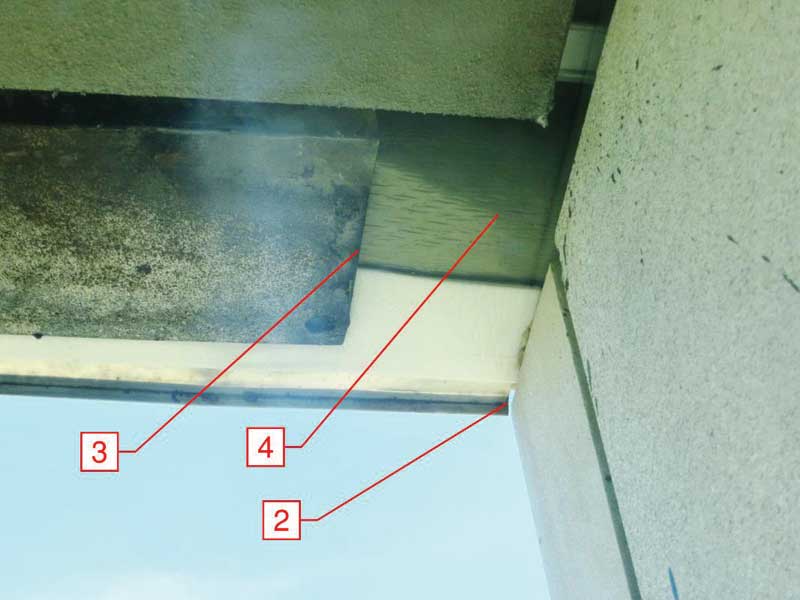

During a visit to review curtain wall assemblies on a project under construction, we noticed something unrelated—brick ties supporting a cantilevered through-wall flashing drip plate at a window opening in the exterior masonry. This unusual condition invited further examination of the cavity wall construction.

The inventive use of brick ties raised concerns about whether the drip plate can be self-supporting (without the ties) and, more importantly, whether the shelf angle below the drip plate was positioned to provide sufficient support for the brick above. (Both American Concrete Institute/American Society of Civil Engineers/The Masonry Society [ACI/ASCE/TMS] 530/530.1, Building Code Requirements and Specification for Masonry Structures and Companion Commentaries, and Brick Industry Association [BIA] Technical Note 21, Brick Masonry Cavity Walls, recommend a minimum of two-thirds bearing for brick veneers.) Extending the metal drip plate beyond the toe of the shelf angle also exposed the adhered foam pad at the underside of the horizontal leg of the metal drip edge to view.

While it was not clear if the membrane flashing continued above the stone piers at each jamb of the masonry opening, the metal drip plate stopped short of the stone piers, and end dams were not provided at terminations in the drip plate. BIA recommends use of a ultraviolet (UV)-stable flashing drip edge (pan or plate) that extends beyond the exterior face of the masonry veneer; there should also be vertical end dams at flashing terminations to prevent lateral water migration from bypassing the flashing plane.

While it was not clear if the membrane flashing continued above the stone piers at each jamb of the masonry opening, the metal drip plate stopped short of the stone piers, and end dams were not provided at terminations in the drip plate. BIA recommends use of a ultraviolet (UV)-stable flashing drip edge (pan or plate) that extends beyond the exterior face of the masonry veneer; there should also be vertical end dams at flashing terminations to prevent lateral water migration from bypassing the flashing plane.

The steel shelf angle (which was anchored to the building structure) also stopped short of the stone piers at the jambs of the opening, resulting in a section of unsupported brick masonry and membrane flashing.

Photos courtesy WJE

Further, a flexible flashing membrane was used to integrate the weather-resistive barrier on the backup wall with the metal drip plate. However, the aforementioned discontinuities in the shelf angle resulted in the unsupported portion of flexible membrane flashing being exposed to environmental conditions. Flexible flashings require continuous support and typically need to be fully concealed, due to their susceptibility to UV degradation.

For this project, investigation of an odd as-built condition led to discovery of a host of conditions bringing into question the long-term serviceability and stability of the exterior masonry above the window. Removal of the brick cladding above the opening will likely be required to properly address the support and flashing issues discovered. Proper development of details, coordination, and execution during exterior wall construction, and a diligent and effective quality assurance/control (QA/QC) program, could have avoided this creative, yet problematic, construction detail.

The opinions expressed in Failures are based on the authors’ experiences and do not necessarily reflect those of the CSI or The Construction Specifier.

Deborah Slaton is an architectural conservator and principal with Wiss, Janney, Elstner Associates (WJE) in Northbrook, Illinois, specializing in historic preservation and materials conservation. She can be reached at dslaton@wje.com.

David S. Patterson, AIA, is an architect and senior principal with the Princeton, New Jersey, office of WJE, specializing in investigation and repair of the building envelope. He can be contacted at dpatterson@wje.com.

Jeffrey N. Sutterlin, PE, is an architectural engineer and senior associate with WJE’s Princeton office, specializing in investigation and repair of the building envelope. He can be reached at jsutterlin@wje.com.

I very much enjoy your columns and have for a number of years. This is a fairly obvious Oops! Being that obvious to a keen observer was this an instance of poor or lacking detail, or did it occur in the execution? Was it repeated in other areas of the facade.

Wouldn’t the services of an Envelope Consultant during the document production and detailing of the building and inspection of installations likely have prevented this situation, and or was it an on the fly installation decision by the General Contractor and it’s Masonry Subcontractor?

Lastly, is this condition going to wait until something falls off, cracks or collapses or is it being proactively remediat ed?

Thanks