Parking garages: Enhancing durability with migrating corrosion inhibitors

by Samantha Ashenhurst | July 17, 2018 9:53 am

[1]

[1]by Julie Holmquist, Casey Heurung, and Jessi Meyer

Parking garages are utilitarian structures designed to hold a large number of vehicles at one time on a comparatively small footprint of land. They must be built to withstand large amounts of weight and vehicle traffic. Durability is key as parking garages are often located in busy metro areas where closure, repair, or reconstruction can be disruptive. Time, labor, and material costs for renovation are also prohibitive. These structures are generally made from reinforced cast-in-place or precast concrete, making corrosion one of the most common challenges to durability.

Corrosion of embedded steel reinforcement in parking garages is brought on by a variety of causes. When new structures are built, the high pH of concrete causes the formation of a natural protective layer on the surface of embedded rebar. As time passes, carbonation eventually sets in and lowers the pH of the concrete, removing the natural protection. The rebar is then vulnerable to the ingress of water, chlorides, or various pollutants. After corrosion initiates, the following vicious cycle begins:

- Corrosion products cause the rebar to expand, putting pressure on the concrete and causing cracks.

- Cracks allow additional water, chlorides, or other contaminants to ingress and attack the embedded rebar, resulting in more corrosion.

- Corrosion on the rebar creates more cracks and eventual spalling, causing the concrete to fall off the surface of the structure, and eventually leave the reinforcing metal exposed.

- If not interrupted, the cycle eventually leads to structural deterioration and deficiency.

Corrosive attack is more severe in certain regions. In northern climates subject to harsh winters with snow and ice, municipalities combat slippery roads and surfaces by using deicing salts. This harsh application of chloride to the concrete surface accelerates the corrosion process and instigates early repairs.

[2]

[2]Photos courtesy Cortec Corp

In coastal environments, concrete structures are attacked by salt spray and high temperatures, intensifying corrosion problems. In coastal areas in the Middle East, the corrosion threat is heightened by high groundwater tables and chloride-rich soils, endangering concrete foundations and requiring special design considerations to provide a long service life.

Countering corrosion

A variety of options exist for countering corrosion on both new and existing structures. Their cost and benefits should be weighed when selecting the right corrosion protection for the job.

Epoxy-coated rebar

Rebar coated with epoxy can be placed in new structures. While this can be very effective as long as the coating lasts, it can also add significant costs to the structure. It is mainly beneficial for new structures, since the idea of replacing the entire network of rebar in existing buildings is impractical, if not impossible. Further, improper application or damage to the epoxy coating can result in accelerated corrosion at localized points, leading to earlier-than-expected failure. (For more information, read the report, “Corrosion of Epoxy Coated Rebar in Florida Bridges,” by Alberto A. Sagüés, et al. here[3].)

Calcium nitrite admixtures

Another strategy employed in new structures is the use of calcium nitrite (CNI) admixtures. These raise the chloride threshold by competing with chlorides for a place on the surface of the rebar. Practically speaking, this means the structure must reach a higher chloride content before a corrosion site can be initiated. However, larger doses (up to 30 L/m3 [6 gal/cy]) of the admixture must be applied to counter the expected rates of chloride exposure. If the threshold is surpassed, corrosion can take place at the same or accelerated rates compared to untreated reinforced concrete. While this treatment can be effective at sufficient doses, it also causes some undesirable side effects. For instance, CNI admixtures accelerate set time and increase shrinkage cracking, making it more difficult to lay and properly finish fresh concrete. As dosage rates increase to compensate for higher chloride exposure, the shrinkage and set time problems are exacerbated, creating more hassle for both the ready mix company and contractors placing the material. CNI also raises health concerns because of its nitrite-based makeup. It is not considered acceptable for use in potable water structures.

[4]

[4]Cathodic protection

Cathodic protection (CP) is another strategy for protection against corrosion. It can be accomplished by redirecting corrosion to a sacrificial anode, or by sending an electric current (impressed current cathodic protection [ICCP]) though the rebar to reroute the normal electrochemical corrosion processes. However, for full effectiveness of CP, all rebar must be continuously connected. In the case of ICCP, the extra cost and maintenance of a constant electrical current has to be taken into consideration.

Concrete water repellents

Applying water repellents to both new and existing structures is a good maintenance practice. These materials discourage corrosion by significantly reducing moisture and chloride ingress into the structure. However, once the repellent layer is compromised, through age or cracking, corrosive elements can work their way to the rebar surface and initiate the corrosion reaction.

Migrating corrosion inhibitor technology

An advantageous strategy for protecting against corrosion on both new and existing structures is the use of migrating corrosion inhibitor technology, introduced into commercial use in the 1980s. This technology is generally safer than calcium nitrite admixtures, and its ability to migrate through the concrete pore structure increases its versatility and effectiveness. It offers standalone protection, but has shown compatibility with other forms of protection, such as CP and water repellents, thereby allowing a multilayered approach to corrosion mitigation in especially rigorous situations. (Consult the presentation, “Evaluation of Interactions between Cathodic Protection and Corrosion,” by Khalil Abed, et al. at the National Association of Corrosion Engineers (NACE) Concrete Service Life Extension Conference in New York City, New York, in June 2017.)

Migrating corrosion inhibitors are based on a blend of salts of amine alcohols (first generation) or amine carboxylates (second generation) with the ability to migrate through concrete and form a protective film on metal surfaces. They can be admixed into new concrete or applied as a liquid surface treatment for penetrating existing concrete. The resulting molecular layer can act as a “mixed” inhibitor to protect against both anodic and cathodic reactions of a corrosion cell.

Migrating corrosion inhibitors can delay the onset of corrosion and also reduce corrosion rates that have already started. For example, one six-and-a-half year independent test of amine carboxylate corrosion inhibiting admixtures concluded time to corrosion was generally two times longer for one migrating corrosion inhibitor (Inhibitor A) and three times longer for another migrating corrosion inhibitor (Inhibitor B). Inhibitor A reduced the total corrosion fourfold, and Inhibitor B reduced the total corrosion as much as 16-fold during the test. The “Report of Concrete Corrosion Inhibitor Testing, Comparative Study” was prepared by American Engineering Testing (AET) in Saint Paul, Minnesota, in August 2002.)

[5]

[5]Photo © BigStockPhoto.com

A first-generation migrating corrosion inhibitor was used on the Randolph Avenue Bridge in Minnesota. The admixture was employed in a 1986 repair on one side of the bridge, while the other side was left untreated. Periodic testing was completed, and by 2011, the untreated side had entered a state of active corrosion, while the treated side was still considered passive with average corrosion rates more than 60 percent lower than the control. (See, “Organic Corrosion Inhibitors – New Build and Existing Structures Performance,” by J. Meyer for the Brian Cherry International Concrete Symposium held in July 2017.)

The difficulty of gathering data on new structures and comparing it to typically non-existent control (untreated) structures of the same type and environment leaves users mainly dependent on standardized test data to estimate the benefit a migrating corrosion inhibitor admixture has on a new structure’s service life. The process is simplified by using service life prediction modeling software. An accessible prediction software available as a free download has been developed by a consortium headed by the American Concrete Institute’s (ACI’s) strategic development council (SDC). The research-based model provides estimates of how design, temperature, chloride exposure, and other factors impact concrete’s service life. (See, “Organic Corrosion Inhibitors – New Build and Existing Structures Performance,” by J. Meyer for the Brian Cherry International Concrete Symposium held in July 2017.) Using inputs based on standardized testing of migrating corrosion inhibitors, engineers can predict an estimated design life for different concrete mix types and climates.

The Princess Tower (the tallest residential-only building when completed in 2012) in the United Arab Emirates was able to upgrade from an estimated 48-year service life for a foundation that did not use inhibitors to a 103-year estimated service life with the use of Inhibitor A. This was at an additional cost of 0.07 percent compared to the rest of the tower’s construction expense. In this case, the modeling software predicted a doubled service life.

Another software model involved a seawall constructed in 2017 on Longboat Key in the Gulf of Mexico. The software was used to help find a mix design with the ability to provide an estimated service life of at least 100 years. The first standard seawall mix input showed an estimated service life of 15.2 years before the first repair would be needed. The addition of Inhibitor A admixture tripled the prediction to 46.9 years of estimated service life before the first repair would be needed. Other mix designs were subsequently tried to find a combination that would meet or exceed the ambitious requirements of the project owner. Eventually, the team settled on a mix design that brought the estimated service life up to more than 100 years on its own. With the addition of Inhibitor A, this estimation increased to more than 150 years.

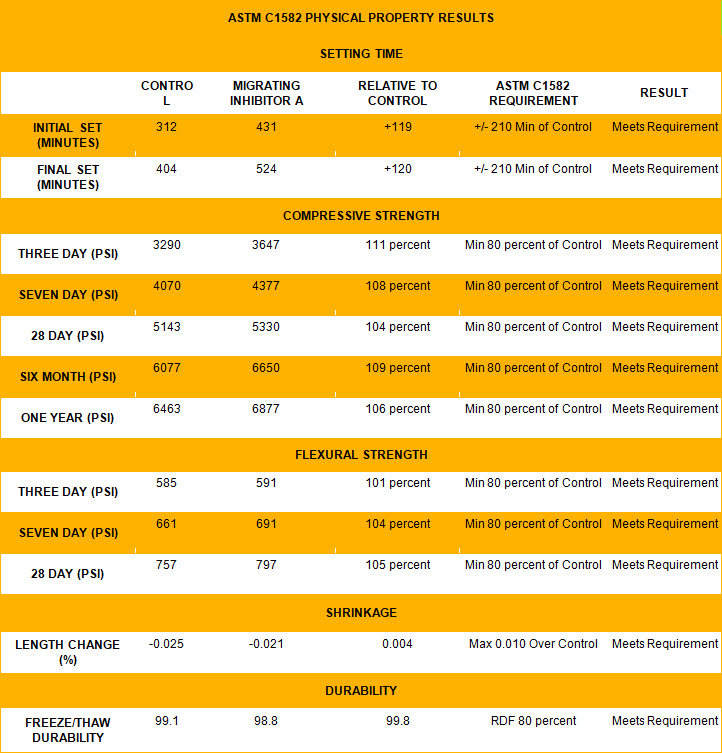

Using inhibitors in new structures

Migrating corrosion inhibiting admixtures have a lot to offer when constructing new parking structures. They tend to have minimal effect on concrete setting properties and allow good workability. Whereas the ASTM C1582, Standard Specification for Admixtures to Inhibit Chloride-Induced Corrosion of Reinforcing Steel in Concrete, requires admixtures meet at least 80 percent of the compressive strength of a control sample not containing corrosion inhibitors, testing showed that Inhibitor A was able to achieve more than 100 percent of the compressive strength of the control at three and 28 days, six months, and one year (Figure 1). Some versions delay concrete mix set time, allowing more time for finishing. However, they can also be prepared as normal set admixtures that neither accelerate set time (a problem with CNI admixtures) nor extend it. Both normal- and extended-set migrating corrosion inhibitor admixtures meet the physical property results regarding set time, compressive and flexural strength, shrinkage, and freeze/thaw durability of ASTM C1582. Also unlike CNI, migrating corrosion inhibitor admixtures of the amine carboxylate blend have been certified by Underwriters Laboratories (UL) to meet NSF International/American National Standards Institute (ANSI) 61, Drinking Water System Components for Use in Potable Water Structures. (For a listing, visit the Underwriters Laboratories (UL) Online Certifications Directory.) Many contain bio-based material (derived from corn), and one has officially been designated as a U.S. Department of Agriculture- (USDA) certified bio-based product under the USDA BioPreferred Program. (For more, click here[6].) Typical dosage is 0.6 to 1 L/m3 (1 to 1.5 pints/yd3), much lower than CNI dosage, which varies dramatically based on expected chloride loading.

[7]

[7]Image courtesy Cortec Corp

[8]

[8]Photos courtesy Smart building

Preparing for harsh winters

Minnesota copes with its harsh winters and slippery roads by using large volumes of deicing salts. These improve driving conditions but contribute heavily to the deterioration of infrastructure. Concrete structures are also subject to multiple freeze-thaw cycles as the weather fluctuates throughout the year. Reinforced concrete bridges and parking structures are prime candidates for the use of migrating corrosion inhibitors to help extend service life in these harsh conditions.

One example of migrating corrosion inhibitor use and its effects on new structures was the design and construction of a parking ramp for Wells Fargo Home Mortgage in Minneapolis. The ramp had to be built within a year, from 2001 to 2002. The design called for six levels with a capacity for 1800 vehicles. Due to time constraints, each deck had to reach 20,684 kPa (3000 psi) strength within 18 to 24 hours of pouring, rather than the standard three days. A superplasticizer was employed to increase the strength and workability of the concrete despite the mix’s low water content.

Though a migrating corrosion inhibiting admixture had been specified, a CNI admixture was employed in the first two floors of the structure due to the expectation of freezing temperatures during construction. The CNI-treated concrete experienced shrinkage cracking and had problems with honeycombing as well as with meeting the required 24-hour strengths. The project reverted to the originally-specified liquid migrating corrosion inhibitor. Shrinkage cracking decreased significantly, and minimum required strength was achieved within the required time. The combination of a migrating corrosion inhibitor admixture and superplasticizer enabled the concrete to exhibit excellent finishing properties. The need for overtime was reduced, and the project was completed four weeks ahead of schedule.

Countering corrosive conditions in the Middle East

Conditions in the United Arab Emirates are corrosive in a very different way. Deicing salts are unnecessary, but high water tables and soils with high chloride content increase the risk of corrosion on reinforcing steel employed in below-ground structural components like foundations. Migrating corrosion inhibitors have been employed in many of structures there (e.g. the foundation of the Burj Khalifa in Dubai, the world’s tallest building) as part of the strategy for achieving sustainability and longer service life.

In contrast to the Minnesota parking garage that needed protection from harsh winter conditions above ground, a three-story, space-saving underground parking garage project in Abu Dhabi, UAE, needed extra protection from the heavy chloride content in the soil. A migrating corrosion inhibitor was specified for admixing into more than 12,000 m3 (15,695 cy) of concrete laid below ground to provide an extra layer of defense against constant exposure to extremely corrosive soil conditions.

Inhibitors for existing parking garages

Migrating corrosion inhibitors can also be used on aging parking garages to reduce existing corrosion rates.

Migrating corrosion inhibitors applied as liquid surface treatments are said to penetrate through concrete pores by the mechanism of capillary action and vapor diffusion. Combined with a silane sealer, they provide two-in-one water-repellent and corrosion inhibiting activity, thereby simplifying the application process. Another advantage of this dual technology is it initially protects against water and chloride ingress, while also providing corrosion-inhibiting action at the level of the rebar in case cracking allows water and salt ingress. For optimal results, application of a migrating corrosion inhibitor surface treatment is recommended once every decade.

Testing according to the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation (USBR) M-82, “Standard Protocol to Evaluate the Performance of Corrosion Mitigation Technologies in Concrete Repairs” showed how three migrating corrosion inhibitor/sealer combinations were able to mitigate corrosion that had already started. The results indicated these inhibitor/sealer combinations were able to do so from a starting point of high chloride content, demonstrating a good potential for the use of migrating corrosion inhibitor/sealer combinations to mitigate corrosion in concrete repairs. (Get more details from the 2015 paper, “Re: USBR M-82 Evaluation of Surface Treatments, TCG Project # 14104” by Tourney Consulting Group.)

[9]

[9]Protecting against ring anode problems

For deeper repairs where concrete spalling is extensive, migrating corrosion inhibitors can be added to the repair mortar for extra protection. This not only enhances the durability of the repair, but also protects against the ring anode effect. A patch of newly laid concrete can cause an electrochemical reaction, spreading corrosion to adjacent concrete because of the difference in corrosion potential on the same piece of rebar. (For more, click here[10].) Using a migrating corrosion inhibitor in the repair mortar or applying a migrating corrosion inhibitor surface treatment around the repair is expected to discourage this because of the inhibitor’s ability to migrate and penetrate into those neighboring areas to form a protective layer on the rebar.

At a parking garage in Cincinnati, Ohio, corrosion problems prompted repairs on a precast slab. Sections of problematic concrete were removed and filled back in with new concrete containing migrating corrosion inhibitors. The inhibitors were intended to mitigate corrosion in the repair areas while also treating against potential ring anode problems from the patch work. A surface treatment of “pure” migrating corrosion inhibitors (no water repellent) was applied for extra protection to areas with heavy reinforcing mats.

Minimizing interruptions

A parking garage in Indianapolis, Indiana, underwent a two-phase maintenance and repair project. The structure was showing wear and needed basic maintenance such as crack injection, expansion joint and paver repair or replacement, and deck sealing. A migrating corrosion inhibitor/water repellant had been used in the first repair phase in 2007 over an area of more than 46,465 m2 (500,000 sf). Since the project provided good results, the owner decided to use a migrating corrosion inhibitor/water repellent in the second phase during 2012, as well. This inhibitor solution was applied with a low-pressure garden sprayer on weekends at a dose of 3.68 m2/L (150 sf/gal). The technology provided minimal interruption, allowing the parking garage to open to traffic during the weekdays.

Conclusion

Migrating corrosion inhibitors are a highly versatile and practical technology for mitigating corrosion on concrete parking garages. Some of their advantages are: they do not negatively affect concrete’s physical properties (as admixtures), they are safer than CNI, and they can be easily used on both new and existing structures. Their many benefits make them an excellent strategy for enhancing the service life of parking garages and countless other valuable structures.

Julie Holmquist is content writer at Cortec Corporation where she researches and writes about corrosion-inhibiting technology for concrete, electronics, metalworking, oil and gas, and other industries. She can be reached at jholmquist@cortecvci.com[11].

Casey Heurung has been a technical service engineer at Cortec Corporation since 2014. His area of concentration is testing and support on the use of migrating corrosion inhibitors for the preservation of reinforced concrete. Heurung holds a bachelor degree in chemistry. He can be reached at cheurung@cortecvci.com[12].

Jessi Meyer is vice-president of sales at Cortec Corporation. She has more than 18 years of experience in the construction and corrosion industries. Meyer holds six patents in the field of corrosion inhibitors used in the concrete/construction market. She has authored several technical papers through National Association of Corrosion Engineers (NACE) and other technical forums. Additionally, Meyer is an active member of the American Concrete Institute (ACI) and the International Concrete Repair Institute (ICRI). She holds bachelor degrees in chemistry and business from the University of Wisconsin. Meyer can be reached at jmeyer@cortecvci.com[13].

- [Image]: https://www.constructionspecifier.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/Image-3.-Cincinnati-garage.Courtesy-SMART.jpg

- [Image]: https://www.constructionspecifier.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/Image-1.-MN-Parking-Garage.-Courtesy-Cortec.jpg

- here: http://sagues.myweb.usf.edu/Documents/FDOT%20Arch/ECR1994AllEle030102.PDF

- [Image]: https://www.constructionspecifier.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/Image-2.-Superplasticizer-migrating-corrosion-inhibitor.-Courtesy-Cortec.jpg

- [Image]: https://www.constructionspecifier.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/bigstock-Snow-Pile-In-Blizzard-Block-Th-240207235.jpg

- here: https://www.biopreferred.gov/BioPreferred/faces/catalog/Catalog.xhtml

- [Image]: https://www.constructionspecifier.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/fig1.jpg

- [Image]: https://www.constructionspecifier.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/Image-4.-Cincinnati-repair-prep.Courtesy-SMART-building.jpg

- [Image]: https://www.constructionspecifier.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/Image-5.-Cincinnati-patchwork.Courtesy-SMART.jpg

- here: https://www.structuraltechnologies.com/solutionbuilder/how-does-the-ringhalo-effect-accelerates-corrosion-outside-of-localized-repairs/

- jholmquist@cortecvci.com: mailto:jholmquist@cortecvci.com

- cheurung@cortecvci.com: mailto:cheurung@cortecvci.com

- jmeyer@cortecvci.com: mailto:jmeyer@cortecvci.com

Source URL: https://www.constructionspecifier.com/parking-garages-enhancing-durability-with-migrating-corrosion-inhibitors/