People Who Work in Glass Houses: Sound masking for modern conference rooms

Diffuse

Diffuse

Diffusion is an acoustical treatment with very little impact on room-to-room sound transmission, but it is worth mentioning for the sake of architectural acoustics, especially in the modern glass conference room. Walls are being composed of glass, ceilings are changing from acoustical tile to gypsum board or just being left open to the hard deck, carpeting is giving way to cement or stone floors, and furnishings are moving toward sleek, hard, minimalism. These modern conference rooms are more reverberant—meaning they echo more. These echoes are especially pronounced when the room has parallel hard surfaces where the sound energy literally bounces back and forth multiple times in a ‘flutter echo.’

Diffusers often take the form of panels added to walls that break up the flat and parallel surfaces so sound energy reflects off in different directions instead of bouncing back and forth. Diffusion can also be designed into the architectural plans in the form of curved walls, uneven surface features such as stone or dimensional tile features, and similar design elements. Some purpose-built acoustical diffusers also offer a small amount of NRC value because they cause small portions of sound waves to cancel themselves. Like absorption, diffusion can help increase speech intelligibility within a room. This is great for presentation spaces or teleconferencing suites, but does not offer much help controlling sound escaping from a conference room into adjoining spaces.

What about speech privacy?

Knowing when and how to apply different treatments can help reduce distractions in open office areas and return some privacy to the modern conference room or ‘private’ office enclosed with demountable walls and glass doors.

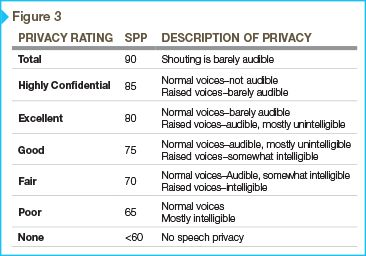

The General Services Administration (GSA) uses a simple measurement called the speech privacy potential (SPP) to compare the reasonable privacy expectations of different spaces (Figure 3). The sum of the noise isolation class of a space should be added to the background noise of the space, and then compared to the chart. A properly installed STC-35 demountable wall added to 30 dB of normal background noise would equal a speech privacy potential of 65, which ranks as ‘poor’—normal voices would be mostly intelligible.

To increase the performance, the STC-35 wall could be switched to a STC-45, or a sound masking system could be introduced to raise background noise to 40 dB. Either way, the result is a speech privacy potential score of 75 which ranks as ‘good’—as normal voices are mostly unintelligible. However, the cost differential will be substantial because sound masking systems tend to be more cost-effective than opting for heavier construction. Additionally, a sound masking system can be ‘turned up’ to bring the background noise level to 42, 45, or 48 dB (the typical industry target for open office areas), which would result in a speech privacy potential score of 83 with no additional cost. This would not be an option with heavier construction.

Sound masking is a contingency plan acknowledging some sound energy will escape the room. Sound energy will travel through the glass walls, find the gaps in the frameless glass doors, push through the absorptive tiles to reflect off the hard deck above, and find its way to the ears of those in the corridors, lobbies, open office areas, or private offices outside. However, if those voices, weakened by their travels, are quieter than the background noise of the space they reach, they will be indistinguishable from that background. In open office space, barriers and absorbers may not even exist anymore, so sound masking is the only way to cover the sounds of carrying voices and reduce the distractions they cause to others working in the space.

Consistency is key

The most important factor in creating an effective sound masking system is consistency. Sound masking does not stop sound from travelling. Instead, it works by playing audible noise into a space to make the background sound level slightly louder than the sounds of people talking from inside private spaces or at distances. If the sound masking in a space is uneven—leaving louder and softer spots within the space—a listener could move to a quieter spot and hear conversations that should otherwise have been covered. Loud spots in a masking system simply become uncomfortable and employees tend to avoid these spaces.

A variation of only 3 dB-SPL is a doubling (or halving) of acoustical energy; therefore, the best sound masking systems aim to deliver consistent sound levels within ± 1 dB throughout the space. Even spacing, consistent level, and zone control account for the differences in acoustical spaces around the office and will all play a part in maintaining an effective, yet comfortable, sound masking system.

Another critical component of a well-designed sound masking system is the spectrum of sound used to increase the background noise level of a space. Technically, the sound is described as a band-limited pink noise with some tonal balancing to focus energy differently around vowels and consonants. In colloquial terms, the random sound projected is called ‘white noise.’

Water features, sounds of rainfall or running streams, HVAC systems, or background music can all serve as a masking function to some degree, but they are not effective or reliable for conference room privacy. Sounds that draw attention to themselves like rainfall or background music might cover up a private conversation, but also increase potential distractions. Water features and HVAC might also cover some conversations when a listener is close enough to the offending noise source, but the inconsistency in level makes them unreliable. The frequency range they cover may also miss the mark on human speech and will likely contain some annoying low frequency content. It is better to stick to a well-engineered and purpose-built sound masking system.