People Who Work in Glass Houses: Sound masking for modern conference rooms

by Katie Daniel | January 6, 2016 12:14 pm

[1]

[1]by Jeremy Krug

Privacy has all but vanished from the modern glass conference room and from much of the open-plan commercial office space. While additional frosting, static films, or vertical blinds can return some small measure of visual privacy, restoring speech privacy through acoustic treatment takes more knowledge, finesse, and careful specification. Acoustic treatment, after all, is not really ‘sound-proofing’ or ‘noise-cancelling.’

Architectural acoustics is the science of controlling sound energy, but there are a few terms that inevitably jump into the discussion because they are common household phrases, although they are widely misunderstood. Without going into too much detail, one should accept ‘sound-proofing,’ in the traditional sense, is really hard to do. In scientific terms, it is close to impossible—acoustical energy is measured to detect earthquakes half a world away, and its energy travels with no regard for fiberglass panels on the walls of 10,000 office suites along the way.

Even controlling weak forces—such as human voices between rooms in purpose-built recording studios, sound stages, or broadcast facilities—is a painstaking process where it is difficult to keep sounds in or out of adjacent spaces. This level of construction is far more specialized and expensive than a typical office space would warrant. While sound-proofing for human voices is not impossible, it is an expensive proposition and the required construction practices frequently run counter to modern office design.

‘Noise-cancelling,’ on the other hand, is somewhat possible in a very small and controllable space—one only needs to know where all the sound is coming from, where it will be heard, and then get in between. For instance, in the small gap between an ear and a set of headphones it is possible to perform some noise cancellation of the world outside. Incoming sounds captured through a microphone must be inverted and processed, and then played back through loudspeakers quickly enough to cancel the original sounds. The mathematics involved in accomplishing this in even a small room is far too chaotic since the sounds can arrive from nearly any direction and the listener can be in almost any position. Therefore, short of requiring everyone in the office to wear isolating headphones (not a very practical solution) true sound cancellation is impossible in this setting.

To understand why these concepts are not quite as easily achieved as might be hoped, and to figure out what options still remain, it is helpful to become a little more familiar with what sound really is and how it interacts with the physical world.

What is sound anyway?

Sound is energy that moves in waves through the air, but not in the simple wavy lines displayed on computer screens. Instead, the movement is a compression wave—a very soft and flexible spring. Air molecules are pushed away from the source and collide with other air molecules (compression)—increasing air pressure at the front of the wave and decreasing pressure behind (rarefaction). For example, the cones of a loudspeaker move back and forth thousands of times a second to literally push and pull the air, creating waves of acoustical energy or sound. The momentum is transferred to the next air molecules in line, while the first group falls back, and so on. This continues back and forth, with the whole process moving away at the source at the speed of sound—about 340 m (1120 ft) per second.

[2]

[2]Sound energy travels out in all directions from the source three-dimensionally. Even when a door is closed and a barrier is created, the sound energy that passes through the gap between the door and floor will not travel out like a laser beam, rather it will spread out spherically again from the gap. Sound energy can transfer from the air through solid materials and back to air again. Its strength is weakened, but some energy still travels through.

Putting a number to it

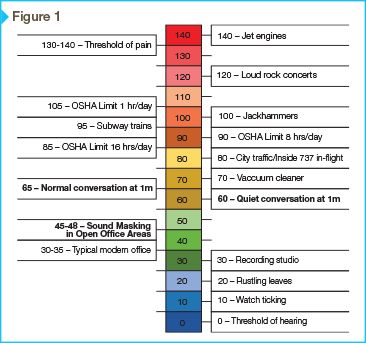

Sound energy is measured in strength or intensity using decibels (dB), and its frequencies are measured in hertz (Hz). The decibel scale can be complicated because it is a logarithmic scale rather than a linear scale—meaning a 10-dB increase in signal is 10 times more energy, not 10 more units of energy. (Further, 3 dB is roughly double the power, 20 dB is 100 times more energy, and so on.) There are also many different decibel scales such as dB-sound power level (SPL), which is used to describe real acoustic energy moving in air. This scale will measure 0 dB-SPL as absolute silence. Typically quiet office ambient noise is around 30 to 35 dB-SPL, conversational speech is around 60 to 65 dB-SPL, and prolonged exposure above 85 dB-SPL is where the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) steps in to regulate exposure and protection rules (Figure 1).

Frequencies in Hz or cycles-per-second are also measured on a logarithmic scale, although for most of architectural acoustics, the ranges are most important. Conveniently, there are just a few key numbers to know. The total range of human hearing runs from about 20 to 20,000 Hz. The equivalent of which would be the rumbling of earthquakes on the low end, up to dog whistles on the high end. The human vocal range runs from about 100 to 8000 Hz, while the critical range actually determines intelligibility or what we understand of human speech runs from about 200 to 5000 Hz. This number is important because covering sound in the critical 200 to 5000 Hz range is what speech privacy is all about.

[3]

[3]The ABCDs of architectural acoustics

There are four main things to consider when controlling sound moving between spaces.

Absorb

The first and perhaps most obvious method of controlling sound energy is through absorption. This controls how sound energy is reflected within an enclosed space. This is generally accomplished with soft materials in an office space. Examples include carpeting, acoustic ceiling tiles, furnishings, and wall-mounted fiberglass panels. The presence of people and even some plants can also contribute.

While these materials will absorb sound, they do not attract sound energy—making absorption difficult because energy travels in all directions. Absorption only works on the energy that reaches the material, and it may not absorb all the energy and thus, allowing some to pass through.

Ceiling tiles in particular have two functional roles for architectural acoustics.

- They help absorb energy bouncing back and forth between walls in an enclosed room, which makes the room echo less and increases vocal clarity within the space.

- They absorb some sound energy radiating upward that would otherwise reflect off the hard deck back down into the room. However, this is not the tile’s primary purpose, and is a measure of its ceiling attenuation (CAC), rather than its noise reduction coefficient (NRC).

Block

Another obvious way to stop sound from reaching unintended ears is to block it—or more accurately, bounce it back into the room from where it is trying to escape. Blocking materials include walls, doors, windows, cubicle dividers, furnishings, and glass panels.

If an object is not an absorber, it is likely reflecting sound energy back into a space. As sound energy travels in all directions and bounces across the room, it will find its way through every gap, crevice, and hole in the blocking material. Sound energy contained within the room is called reverberation, and will bounce around until it escapes, decays, or is absorbed. This reverberation can be especially troublesome for teleconferencing systems since it makes the voices sound more distant to those on the other end of the call. (The ‘Auto Echo Cancellation’ feature does not apply to this kind of echo.) No surface is a perfect reflector either, and some energy will travel through the solid blocking material.

In simplified terms, STC is a measure of how much sound energy is blocked versus how much is transmitted through the material when averaged across a frequency range of roughly 125 to 5000 Hz. The higher the STC number the more energy blocked by the assembly. However, when working from the numbers specified for particular construction products, the entire assembly must be taken into account. For example, a very expensive STC-50 door will not function to specification if it is installed into an STC-30 wall. When working with modern demountable walls, that a manufacturer may provide a laboratory-tested specification of STC-45, but the field-tested performance will depend on the quality of installation labor and the attention to detail of the complete wall assembly installation. If any of the fit or finish is off-kilter and does not sit quite right, air gaps and uneven seals will decrease the STC rating.

Cover

Covering sound energy with more sound to increase privacy and reduce distractions can seem counter-intuitive, but it is very effective and is already happening in many office spaces to some degree. ‘Sound masking’ is the process of adding low-level background sound to an environment to promote speech privacy and freedom from distractions.

When using the photocopier, one may be unable to overhear conversations, but again discern discussions when the machine stops. This same principle applies when speaking in a loud environment. When background noise is loud, people raise their voices above it to be heard. This difference in sound energy between speech and background noise is the signal-to-noise ratio.

Normal conversational speech measures between 60 to 65 dB, while typical background noise levels

of a modern office space are about 30 to 35 dB—a difference of 30 to 40 dB between the signal (speech) and the noise. Lower signal-to-noise ratios mean it is harder to distinguish the signal from the noise, and higher ratios mean it is easier. A signal-to-noise ratio of only 15 dB represents near-perfect speech intelligibility, and 30 to 40 dB is fantastically clear—better than an emergency notification system would be expected to achieve. It is important to remember a 10-dB change is 10 times the sound energy, so 30 dB is 1000 times more acoustical energy.

[4]

[4]For offices, the goal is to have very low signal-to-noise ratio across the critical range of human hearing. Introducing sound masking to increase the normal background office noise from 30 to 35 dB up to between 42 to 48 dB, and specifically tuning the masking noise to the human range of speech, can have a huge impact on increasing privacy. The key difference between covering speech versus absorbing or blocking it is masking covers the sound energy that has already escaped other attempts at containment. Essentially, sound masking anticipates the shortcomings of attempts to absorb or block sound.

A common misunderstanding when considering sound masking is its placement. For instance, placing the speakers inside the room to be masked is incorrect. Masking relies on the voices to be weakened by distance and other obstructions. Therefore, the sound masking speakers should go where the overhearing ears are (Figure 2). The sound is already weaker at this location so a little increase in background noise makes it unintelligible. To mask the sound from the source the location of the person speaking would have to be masked. The background noise would have to be louder than the person speaking, and then nobody would be able to hear him or her—even inside the conference room. Instead, the sound masking is positioned to prevent the unintended listeners from hearing something they do not want, or should not, hear.

[5]Diffuse

[5]Diffuse

Diffusion is an acoustical treatment with very little impact on room-to-room sound transmission, but it is worth mentioning for the sake of architectural acoustics, especially in the modern glass conference room. Walls are being composed of glass, ceilings are changing from acoustical tile to gypsum board or just being left open to the hard deck, carpeting is giving way to cement or stone floors, and furnishings are moving toward sleek, hard, minimalism. These modern conference rooms are more reverberant—meaning they echo more. These echoes are especially pronounced when the room has parallel hard surfaces where the sound energy literally bounces back and forth multiple times in a ‘flutter echo.’

Diffusers often take the form of panels added to walls that break up the flat and parallel surfaces so sound energy reflects off in different directions instead of bouncing back and forth. Diffusion can also be designed into the architectural plans in the form of curved walls, uneven surface features such as stone or dimensional tile features, and similar design elements. Some purpose-built acoustical diffusers also offer a small amount of NRC value because they cause small portions of sound waves to cancel themselves. Like absorption, diffusion can help increase speech intelligibility within a room. This is great for presentation spaces or teleconferencing suites, but does not offer much help controlling sound escaping from a conference room into adjoining spaces.

What about speech privacy?

Knowing when and how to apply different treatments can help reduce distractions in open office areas and return some privacy to the modern conference room or ‘private’ office enclosed with demountable walls and glass doors.

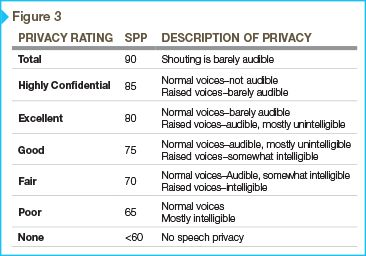

The General Services Administration (GSA) uses a simple measurement called the speech privacy potential (SPP) to compare the reasonable privacy expectations of different spaces (Figure 3). The sum of the noise isolation class of a space should be added to the background noise of the space, and then compared to the chart. A properly installed STC-35 demountable wall added to 30 dB of normal background noise would equal a speech privacy potential of 65, which ranks as ‘poor’—normal voices would be mostly intelligible.

To increase the performance, the STC-35 wall could be switched to a STC-45, or a sound masking system could be introduced to raise background noise to 40 dB. Either way, the result is a speech privacy potential score of 75 which ranks as ‘good’—as normal voices are mostly unintelligible. However, the cost differential will be substantial because sound masking systems tend to be more cost-effective than opting for heavier construction. Additionally, a sound masking system can be ‘turned up’ to bring the background noise level to 42, 45, or 48 dB (the typical industry target for open office areas), which would result in a speech privacy potential score of 83 with no additional cost. This would not be an option with heavier construction.

Sound masking is a contingency plan acknowledging some sound energy will escape the room. Sound energy will travel through the glass walls, find the gaps in the frameless glass doors, push through the absorptive tiles to reflect off the hard deck above, and find its way to the ears of those in the corridors, lobbies, open office areas, or private offices outside. However, if those voices, weakened by their travels, are quieter than the background noise of the space they reach, they will be indistinguishable from that background. In open office space, barriers and absorbers may not even exist anymore, so sound masking is the only way to cover the sounds of carrying voices and reduce the distractions they cause to others working in the space.

Consistency is key

The most important factor in creating an effective sound masking system is consistency. Sound masking does not stop sound from travelling. Instead, it works by playing audible noise into a space to make the background sound level slightly louder than the sounds of people talking from inside private spaces or at distances. If the sound masking in a space is uneven—leaving louder and softer spots within the space—a listener could move to a quieter spot and hear conversations that should otherwise have been covered. Loud spots in a masking system simply become uncomfortable and employees tend to avoid these spaces.

A variation of only 3 dB-SPL is a doubling (or halving) of acoustical energy; therefore, the best sound masking systems aim to deliver consistent sound levels within ± 1 dB throughout the space. Even spacing, consistent level, and zone control account for the differences in acoustical spaces around the office and will all play a part in maintaining an effective, yet comfortable, sound masking system.

Another critical component of a well-designed sound masking system is the spectrum of sound used to increase the background noise level of a space. Technically, the sound is described as a band-limited pink noise with some tonal balancing to focus energy differently around vowels and consonants. In colloquial terms, the random sound projected is called ‘white noise.’

Water features, sounds of rainfall or running streams, HVAC systems, or background music can all serve as a masking function to some degree, but they are not effective or reliable for conference room privacy. Sounds that draw attention to themselves like rainfall or background music might cover up a private conversation, but also increase potential distractions. Water features and HVAC might also cover some conversations when a listener is close enough to the offending noise source, but the inconsistency in level makes them unreliable. The frequency range they cover may also miss the mark on human speech and will likely contain some annoying low frequency content. It is better to stick to a well-engineered and purpose-built sound masking system.

R-value ≠ STC

There is a common misconception that increasing thermal insulation is a way of returning privacy to the conference room and open office environment. If the sound escaping is leaving through the ceiling, and if the insulation is installed consistently, it might provide some benefit to reducing some of the sound travel. However, simply doubling the R-value of a wall or ceiling system will not double the STC because the sound transmission class is a measure of the entire system’s performance, of which the insulation is only a small component.

It is also important to remember sound levels measured in decibels are a logarithmic scale. Increasing the performance of a 35 STC wall system to hold back double the sound energy is only an increase to 38 STC, not to 70 STC. This is why a 55 STC door is so much more expensive than a 35 STC. The 55 STC holds back 100 times more sound energy than its lower-cost counterpart.

As an absorber, insulation will only have an effect on sound energy that actually reaches the material. Here again, ceiling insulation has no attractive power to draw in sound energy headed for the gap between the frameless glass doors of the boardroom. It is often better to investigate adding an entirely different class of acoustic treatment before trying to double down on the performance of a treatment already in place, or to try using thermal insulation as a barrier to contain sound.

Conclusion

It is safe to say the glass houses of modern conference rooms are with us for the foreseeable future. With office space at a premium in many markets, open-plan offices, tighter employee seating, and limited acoustical treatments are all design features that will be around for a while. Conversations in open spaces will continue to distract employees trying to focus on their work, while private conversations that should not be overheard will be an increasing concern of employers, employees, and legal organizations. Sound management, and especially sound masking, is an important part in the mitigation of sound for these new open and glass-enclosed office spaces.

Jeremy Krug has more than 15 years of experience as a professional audio engineer. He studied music performance at The Harid Conservatory and Colorado University (CU)-Boulder, and audio engineering at the CU-Denver. Krug served for almost a decade as the recording studio engineer for the School of Music at Washington State University, and has worked in both residential and commercial audio visual (A/V) integration. Krug joined the team at Cambridge Sound Management in 2014. He can be reached via e-mail as jkrug@cambridgesound.com[6].

- [Image]: http://www.constructionspecifier.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/01/Cover-Glass-Room-Option-02.jpg

- [Image]: http://www.constructionspecifier.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/01/sound_figure1.jpg

- [Image]: http://www.constructionspecifier.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/01/bigstock-Photo-Of-Skyline-Music-Diffuso-74649199.jpg

- [Image]: http://www.constructionspecifier.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/01/Figure-02-Masking-Outside-Room.jpg

- [Image]: http://www.constructionspecifier.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/01/sound_figure3.jpg

- jkrug@cambridgesound.com: mailto:jkrug@cambridgesound.com

Source URL: https://www.constructionspecifier.com/people-who-work-in-glass-houses-sound-masking-for-modern-conference-rooms/