Image courtesy Building Science Corporation

Crucial role of air barriers to prevent moisture intrusion

By far, air is the most significant mechanism of water vapor transport, and vapor goes where the air goes. All air, whether it is inside or outside of buildings, is constantly moving from high- to low-pressure areas. If dry air is pulled into the building from outdoors, it will dehumidify the indoor air. If humid air is pulled in, it will add to the humidity load, which must be removed by the mechanical ventilation system.

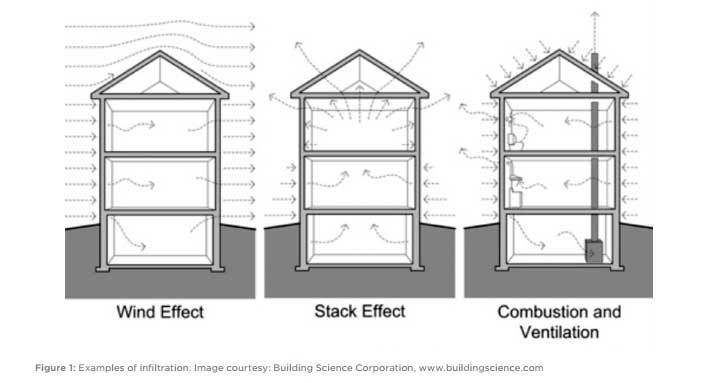

As Figure 1 demonstrates, airflow occurs in different ways. Understanding what creates the differences in pressure—whether it is wind, stack effect, or use of HVAC and other appliances—is the key to optimizing the air barrier system.

To achieve a sound structure and a healthy interior environment, building designers need to address heat and moisture flow as well as the effects of solar radiation. However, engineering experts now believe managing airflow is the most influential factor in controlling ambient heat and moisture.

According to the Building Science Corporation, airflow carries moisture that impacts the long-term performance of materials (‘serviceability’) and a building’s structural integrity (‘durability’). Airflow also affects indoor air quality (IAQ) and thermal energy consumption, as well as building performance in a fire, by regulating the generation of smoke and toxic gases and the supply of oxygen. The air barrier system can also act as the ‘gas barrier,’ providing a gas-tight separation between a residential garage and adjacent living spaces.

The best strategy for the control of airflow and related moisture intrusion in buildings is an effective air barrier system.

Types of air barriers

A proper air barrier system keeps ‘unconditioned’ outside air out of the building enclosure or inside ‘conditioned’ air from escaping from the building enclosure—depending on climate or configuration. Some air barriers do both.

Air barrier systems can be positioned anywhere in the building enclosure—at the wall’s exterior or interior surface, or anywhere in between. They vary according to climate conditions because air naturally gravitates from warm to cold. In cold climates, interior air barrier systems control the filtration of interior—often moisture-laden—air as it moves out of the enclosure. Exterior air barrier systems control the passage of outside air in, while containing the effects of wind as it passes through or behind the thermal insulation within enclosures, causing significant loss of heat flow control and potentially causing condensation.

Photos courtesy Sto Corp

Air barriers are intended to resist the pressure acting on them. To meet current energy code requirements, they must be properly installed to create a continuous building envelope—one restricting air and moisture migration. The most vulnerable spots are at any penetration points, including fasteners, detailing around windows, and material transitions (e.g. fiber sheathing and CMUs), which need to be covered or sealed. There must be a protective continuity in the barrier to offset these vulnerabilities and prevent unwanted air and moisture from entering.

Numerous approaches can be used to provide air barrier systems in buildings, and varying based on the adopted energy codes where the structure is located. They can range from concrete walls, wood, rigid foam, and gypsum sheathing to self-adhered sheet membranes, housewraps, and liquid-applied membranes—each material has its own benefits and considerations. For example, air barriers can be combined with WRBs, and they come in several forms: traditional housewraps, peel-and-stick membranes, and fluid-applied membranes—the latter being the most recently developed. Housewraps are more economical. Peel-and-stick membranes ensure a tight envelope using a factory controlled thickness, while fluid-applied come in both thin and thick applications, provide a tight envelope, and make detailing easy (roller or spray versus cutting and measuring wraps or peel-and-sticks).

According to this quotation from the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA):

Building enclosures should be designed to prevent condensation and achieve an airtight exterior enclosure using continuous air barrier systems around the entire enclosure. These systems greatly reduce the leakage of inside air into the exterior enclosure assemblies during cold weather and the leakage of outdoor air into the exterior enclosure or interior wall, ceiling, and floor cavities during warm weather. Air sealing an enclosure makes it easier to manage indoor-outdoor air pressure relationships with practical airflow rates, and allows the assembly to dry out if it gets wet.

(Visit www.epa.gov/sites/production/files/2014-08/documents/moisture-control.pdf to read Moisture Control Guidance for Building Design, Construction and Maintenance, published in December 2013 by EPA.)

To achieve the best airtight building enclosure to prevent condensation, an effective air barrier system must be air-impermeable, meaning it restricts airflow. It should be applied continuously throughout the entire building enclosure or throughout the enclosure of any given unit.

Code requirements for air barrier systems typically require a continuous plane of airtightness traced throughout the building, and walls should be sufficiently airtight to limit water vapor migration. Penetrations must be sealed, and an air barrier must be provided between spaces having significantly different temperature or humidity requirements.

In meeting these requirements, the idea is to select and target a component of the wall or roof that is impermeable to air, and to create an airtight ‘assembly’ by sealing the joints and penetrations. The air barrier must be continuous, from roof and floor line to basement, and account for the transitions for doors, windows, and other elements possibly compromising the airtight integrity. Each of these penetrations must be sealed off, and the air protection for each component must be tied in to related components to form an airtight system.

To complete the air barrier system of the building, the above-grade system needs to be connected to the foundation walls and basement slabs. Air sealing below-grade walls and slabs in a building will prevent entry of not only moisturized air, but also dangerous gases such as radon and other environmental pollutants.

According to Lsiturbek, the following are the important features of an air barrier system.