The Perils of Moisture: Using air barriers to manage water intrusion

by Katie Daniel | February 5, 2018 10:31 am

[1]

[1]by Karine Galla

Every professional builder knows about the damaging effects of unwanted moisture, as well as how challenging it is to control water intrusion in certain climates. However, What is not always understood is the role airflow plays in moisture control and how important air barriers are in managing it.

Water intrusion is bad for any structure, and air carries a lot of it. Keeping air from invading a building envelope is essential, and if there is leakage into the structure, one has to ensure this airflow does not get cold enough to condense and create moisture.

Managing the exterior flow of air is also important to dry out the wall system when moisture has found a way in. Additionally, restricting air from flowing unimpeded through a wall system can prevent the invasion of allergens, pollutants, and bacteria, which can compromise the health of building occupants.

This is why the air barrier should be vapor-permeable—the wall can ‘breathe’ and dry out, but the air cannot make its way past the sheathing and reach the inside wall cavity.

When insulation gets wet, it quickly loses its ability to resist thermal flow and has a negative effect on energy efficiency. Moisture-laden insulation reduces R-values, resulting in rising energy costs. There are also the damaging effects of capillarity (i.e. the tendency of water to flow through narrow spaces). However, by properly controlling air pressure inside the wall system, it is possible to reduce accumulation of moisture.

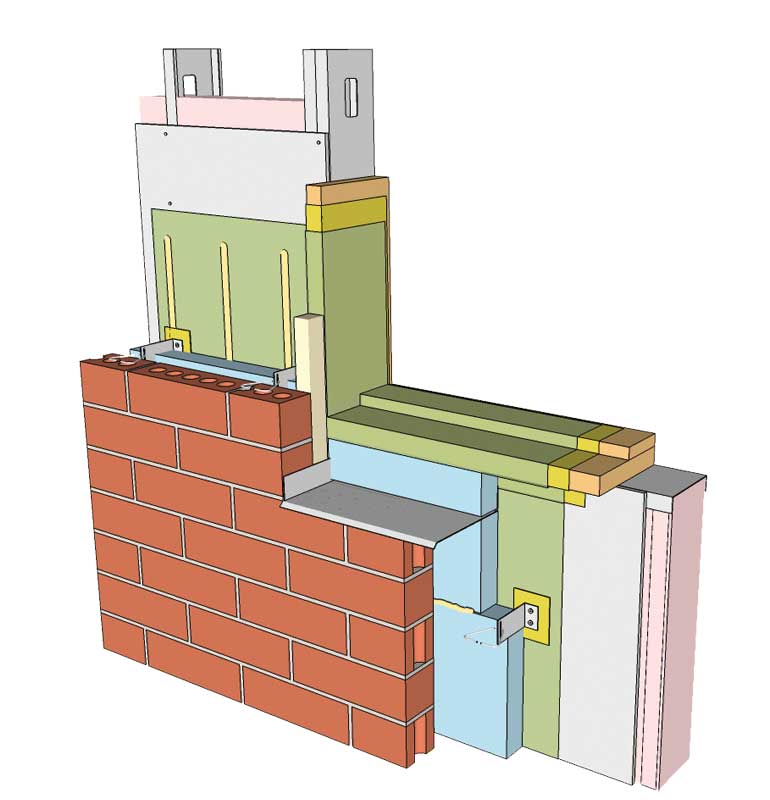

Air invariably moves. Moisture cannot be effectively controlled unless the air is first managed. Therefore, a highly airtight enclosure is necessary to provide conditioning, as well as temperature and humidity control. The best place to control this atmospheric element is on the outside of the sheathing, but under the insulation layer so the air temperature remains more or less static.

[2]

[2]Air barriers vs. moisture barriers

At this point, it may be helpful to differentiate between a water-resistive barrier (WRB) and an air barrier. The function of a moisture barrier is to keep liquid H2O from entering the building enclosure. Combined with flashing, drain plane, sheathing, and other wall components, the moisture barrier provides a protective layer keeping water away from the stud cavity.

The role of an air barrier is to resist leakage. As explained by American Society of Heating, Refrigerating, and Air-conditioning Engineers (ASHRAE) Fellow Joseph Lstiburek, PhD, P.Eng. (founding principal of Building Science Corporation, a consulting and architectural firm), “Air barriers are systems of materials designed and constructed to control airflow between a conditioned space and an unconditioned one. The system is the primary air enclosure boundary separating indoor (conditioned) and outdoor (unconditioned) air.”

Air leakage loads are significantly greater than most designers and architects commonly realize. Many materials have been considered suitable air barriers, including gypsum wallboard, building felt, and concrete masonry units (CMUs). However, as building codes change and airtightness requirements increase, some of these materials may no longer be considered code-approved.

Vapor barriers should not be confused with air barriers. The former is designed to inhibit the flow of water vapor through a given material, and is intended to control the rate of diffusion into a building assembly.

Vapor dissemination has been traditionally considered a key component of moisture control. However, modern building science suggests air leakage—and not vapor diffusion—is the more serious problem. In fact, for a given wall, moisture transmitted via air leakage is 200 times higher than through vapor diffusion. (Read R. Quirouette’s The Difference Between a Vapor Barrier and an Air Barrier[3], published by National Research Council Canada in 1985.)

[4]

[4]Image courtesy Building Science Corporation

Crucial role of air barriers to prevent moisture intrusion

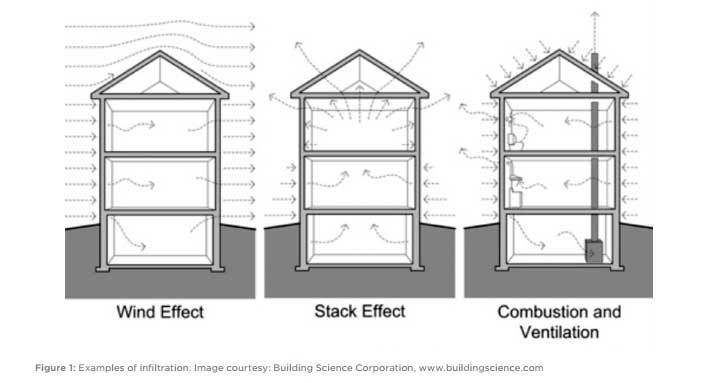

By far, air is the most significant mechanism of water vapor transport, and vapor goes where the air goes. All air, whether it is inside or outside of buildings, is constantly moving from high- to low-pressure areas. If dry air is pulled into the building from outdoors, it will dehumidify the indoor air. If humid air is pulled in, it will add to the humidity load, which must be removed by the mechanical ventilation system.

As Figure 1 demonstrates, airflow occurs in different ways. Understanding what creates the differences in pressure—whether it is wind, stack effect, or use of HVAC and other appliances—is the key to optimizing the air barrier system.

To achieve a sound structure and a healthy interior environment, building designers need to address heat and moisture flow as well as the effects of solar radiation. However, engineering experts now believe managing airflow is the most influential factor in controlling ambient heat and moisture.

According to the Building Science Corporation, airflow carries moisture that impacts the long-term performance of materials (‘serviceability’) and a building’s structural integrity (‘durability’). Airflow also affects indoor air quality (IAQ) and thermal energy consumption, as well as building performance in a fire, by regulating the generation of smoke and toxic gases and the supply of oxygen. The air barrier system can also act as the ‘gas barrier,’ providing a gas-tight separation between a residential garage and adjacent living spaces.

The best strategy for the control of airflow and related moisture intrusion in buildings is an effective air barrier system.

Types of air barriers

A proper air barrier system keeps ‘unconditioned’ outside air out of the building enclosure or inside ‘conditioned’ air from escaping from the building enclosure—depending on climate or configuration. Some air barriers do both.

Air barrier systems can be positioned anywhere in the building enclosure—at the wall’s exterior or interior surface, or anywhere in between. They vary according to climate conditions because air naturally gravitates from warm to cold. In cold climates, interior air barrier systems control the filtration of interior—often moisture-laden—air as it moves out of the enclosure. Exterior air barrier systems control the passage of outside air in, while containing the effects of wind as it passes through or behind the thermal insulation within enclosures, causing significant loss of heat flow control and potentially causing condensation.

[5]

[5]Photos courtesy Sto Corp

Air barriers are intended to resist the pressure acting on them. To meet current energy code requirements, they must be properly installed to create a continuous building envelope—one restricting air and moisture migration. The most vulnerable spots are at any penetration points, including fasteners, detailing around windows, and material transitions (e.g. fiber sheathing and CMUs), which need to be covered or sealed. There must be a protective continuity in the barrier to offset these vulnerabilities and prevent unwanted air and moisture from entering.

Numerous approaches can be used to provide air barrier systems in buildings, and varying based on the adopted energy codes where the structure is located. They can range from concrete walls, wood, rigid foam, and gypsum sheathing to self-adhered sheet membranes, housewraps, and liquid-applied membranes—each material has its own benefits and considerations. For example, air barriers can be combined with WRBs, and they come in several forms: traditional housewraps, peel-and-stick membranes, and fluid-applied membranes—the latter being the most recently developed. Housewraps are more economical. Peel-and-stick membranes ensure a tight envelope using a factory controlled thickness, while fluid-applied come in both thin and thick applications, provide a tight envelope, and make detailing easy (roller or spray versus cutting and measuring wraps or peel-and-sticks).

According to this quotation from the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA):

Building enclosures should be designed to prevent condensation and achieve an airtight exterior enclosure using continuous air barrier systems around the entire enclosure. These systems greatly reduce the leakage of inside air into the exterior enclosure assemblies during cold weather and the leakage of outdoor air into the exterior enclosure or interior wall, ceiling, and floor cavities during warm weather. Air sealing an enclosure makes it easier to manage indoor-outdoor air pressure relationships with practical airflow rates, and allows the assembly to dry out if it gets wet.

(Visit www.epa.gov/sites/production/files/2014-08/documents/moisture-control.pdf[6] to read Moisture Control Guidance for Building Design, Construction and Maintenance, published in December 2013 by EPA.)

[7]

[7]To achieve the best airtight building enclosure to prevent condensation, an effective air barrier system must be air-impermeable, meaning it restricts airflow. It should be applied continuously throughout the entire building enclosure or throughout the enclosure of any given unit.

Code requirements for air barrier systems typically require a continuous plane of airtightness traced throughout the building, and walls should be sufficiently airtight to limit water vapor migration. Penetrations must be sealed, and an air barrier must be provided between spaces having significantly different temperature or humidity requirements.

In meeting these requirements, the idea is to select and target a component of the wall or roof that is impermeable to air, and to create an airtight ‘assembly’ by sealing the joints and penetrations. The air barrier must be continuous, from roof and floor line to basement, and account for the transitions for doors, windows, and other elements possibly compromising the airtight integrity. Each of these penetrations must be sealed off, and the air protection for each component must be tied in to related components to form an airtight system.

To complete the air barrier system of the building, the above-grade system needs to be connected to the foundation walls and basement slabs. Air sealing below-grade walls and slabs in a building will prevent entry of not only moisturized air, but also dangerous gases such as radon and other environmental pollutants.

According to Lsiturbek, the following are the important features of an air barrier system.

[8]

[8]Continuity

To ensure continuity, each component (a wall, window assembly, foundation, or roof) must be interconnected to prevent air leakage at the joints between materials, components, assemblies, systems, and penetrations through them, such as conduits and pipes.

Structural support

Every component of a building’s air barrier system must withstand the stresses and loads placed on it by the forces of wind, the building’s size and shape, or operating systems, and designed to transfer these loads to the structure itself. The design of the system must also account for the fact the balance of air moving in and out of the structure will not compromise structural integrity.

Air impermeability

Materials that are too air-permeable (i.e. they allow an excess of air molecules to pass through a membrane under pressure) must be avoided. The air permeance is measured using ASTM E2178, Standard Test Method for Air Permeance of Building Materials, which requires air leakage be less than 0.02 L/s∙m² @ 75 Pa (0.004 cfm/sf @ 1.57 lb/sf). (More information on the permeance of building materials can be found in “Air Permeance of Building Materials[9].”) Other industry groups may require tighter standards, such as the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (USACE), the Naval Facilities Command (NAVFAC), or the Air Barrier Association of America (ABAA). Section 5.4.3.1.3, Acceptable Materials and Assemblies of ASHRAE 90.1, Energy Standard for Buildings Except Low-rise Residential Buildings, has the same requirement as ASTM E2178.

Durability

Materials chosen for the air barrier system must be long-lasting and fulfill their purpose for the expected life of the structure. Alternatively, the product must be accessible for periodic maintenance.

Material selection and specifications

The correct layer of material for the wall assembly must be chosen to form the basis of the air barrier system. Popular choices include interior gypsum or foam, sprayed polyurethane foam (SPF) insulation, concrete, oriented strand board (OSB), or plywood deck. The accessory materials must ensure the durable continuity of the air barrier.

[10]

[10]One must also know all the specifications detailing methods for ensuring the air barrier continuity, especially at:

- penetrations, corners, and edges (e.g. rough openings for windows, doors, pipes, shafts, and conduits);

- at transitions between one material and another (e.g. wall-ceiling intersections and wall-floor intersections); and

- where the air barrier must pass around structural elements (e.g. heavy vertical steel posts or horizontal beams).

The ‘Pen Test’ is an easy way to gauge the effectiveness of the planned moisture-control elements. This is a proven way to verify the continuity of the insulation, air barrier, and WRB. It consists of color-coding the ‘barrier’ on a detail from the roof to the basement around the entire structure. When following the line, the pen must not come off the paper; the line (and therefore the air barrier) must be continuous. This visual measure makes it easy for all the trades involved in the construction and maintenance of the building to see where the barrier is and how to handle the detailing. It is the fastest and easiest way for designers and applicators to make sure they’re going to achieve a tight envelope on a given project. (Related drawings are online at b[11]uildingscienceeducation.net/wp-content/uploads/2014/09/Pen-Test-Moisture-Control-Guidance-for-Building-Design-Construction-and-Maintenance.pdf[12].)

For additional guidance, ABAA offers excellent support for the design of durable walls by providing open access to a library of master specifications for the various types of air barriers. ABAA defines a successful air barrier as one that:

- reduces required HVAC system size while improving efficiency;

- manages air pressure differentials properly;

- enables water vapor to escape from wall cavities;

- enhances IAQ; and

- improves occupant comfort through reduced drafts.

Conclusion

Air barriers are increasingly being combined by manufacturers into integrated air and moisture barrier systems, which address the demands of today’s more stringent, energy-efficient building codes.

In addition to enhancing IAQ, the comfort of building occupants, and energy savings, there are real economic benefits to controlling air leakage throughout the building envelope. In fact, research has shown air barriers can play a larger role in enhancing energy efficiency than increasing the thickness of standard insulation. High-performance air barriers can not only save on operational energy costs and often offset some construction or retrofit costs, but also open the door to reductions in the size of heating and cooling units.

It is important to remember controlling moisture means controlling airflow—one should never underestimate the value of an effective air barrier system.

Karine Galla is product manager for Sto Corp. She has more than 16 years of experience in product marketing regarding EIFS, stucco, air and moisture barriers, and other materials. Galla has a master’s degree from the University of Lyon, France. She holds the Association of the Wall and Ceiling Industry’s (AWCI’s) EIFS Doing it Right and Building Envelope Doing it Right certifications, as well as the ISO Internal Lead Auditor certification from Georgia Tech. She can be reached at KGalla@StoCorp.com[13].

- [Image]: https://www.constructionspecifier.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/GablesMidtown.jpg

- [Image]: https://www.constructionspecifier.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/61s.jpg

- The Difference Between a Vapor Barrier and an Air Barrier: http://www.healthyheating.com/HH_Integrated_Design/Week%204/The%20Difference%20Between%20a%20Vapor%20Barrier%20and%20an%20Air%20Barrier.pdf

- [Image]: https://www.constructionspecifier.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/Building-Science.jpg

- [Image]: https://www.constructionspecifier.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/Boone-Hospital.jpg

- www.epa.gov/sites/production/files/2014-08/documents/moisture-control.pdf: http://www.epa.gov/sites/production/files/2014-08/documents/moisture-control.pdf

- [Image]: https://www.constructionspecifier.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/Chapala-One.jpg

- [Image]: https://www.constructionspecifier.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/Gables-Property.jpg

- Air Permeance of Building Materials: http://www.cmhc-schl.gc.ca/publications/en/rh-pr/tech/98109.htm

- [Image]: https://www.constructionspecifier.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/Okon.jpg

- b: http://uildingscienceeducation.net/wp-content/uploads/2014/09/Pen-Test-Moisture-Control-Guidance-for-Building-Design-Construction-and-Maintenance.pdf

- uildingscienceeducation.net/wp-content/uploads/2014/09/Pen-Test-Moisture-Control-Guidance-for-Building-Design-Construction-and-Maintenance.pdf: http://uildingscienceeducation.net/wp-content/uploads/2014/09/Pen-Test-Moisture-Control-Guidance-for-Building-Design-Construction-and-Maintenance.pdf

- KGalla@StoCorp.com: mailto:KGalla@StoCorp.com

Source URL: https://www.constructionspecifier.com/perils-moisture-using-air-barriers-manage-water-intrusion/