Perimeter Fire Barrier Systems: Taking a team approach to fire-safe construction

by Katie Daniel | September 8, 2017 2:35 pm

[1]

[1]by Tony Crimi, P.Eng., MASc.

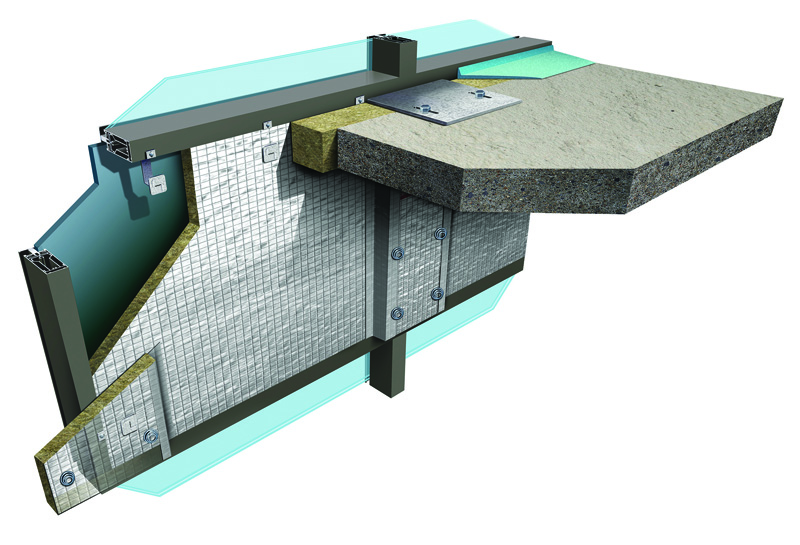

Building owners and occupants often take fire safety for granted. They assume that buildings are constructed with fire safety in mind and significant attention has been paid to building codes. Nevertheless, there exists one particularly critical juncture frequently overlooked in fire-safe design—the void space between an exterior curtain wall and the edge of the floor. This area can be addressed by perimeter fire barrier systems.

Unlike some fire safety elements addressed primarily through design and specification decisions, perimeter fire barrier systems require careful attention to design, specification, and installation to work properly. Consequently, they demand close collaboration by the architect, specifier, and general contractor to ensure each link in the chain is appropriately addressed.

This article provides a background on the importance of perimeter fire barrier systems, as well as actionable guidance for architects, specifiers, and general contractors to ensure they deliver the level of fire safety their customers have come to expect.

Overview of fire and life safety

According to National Fire Protection Association (NFPA) statistics, there is one structure fire in the United States every 63 seconds. From 2009 to 2013, U.S. fire departments responded to an estimated average of 14,500 reported structure fires in high-rise buildings annually. (This comes from the NFPA’s November 2016 publication, “High-rise Building Fires Report,” by M. Ahrens. Visit www.nfpa.org/news-and-research/fire-statistics-and-reports/fire-statistics/fires-by-property-type/high-rise-building-fires[2].)

During this same time period, high-rise building fires caused an annual average of 40 civilian deaths and 520 injuries, along with $154 million in direct property damage (i.e. not including reputation damage or litigation costs). Five property types account for three-quarters of high-rise fires:

- apartments or other multifamily housing;

- hotels;

- dormitories;

- facilities offering care for the sick; and

- office buildings.

In the early 1970s, the construction industry began to recognize fires in buildings with curtain wall construction were reaching through windows and traveling from floor to floor. Major fires in the United States and Mexico prompted suppliers, code officials, and model code groups to seek passive systems that could contain a fire at the building’s perimeter. Various insulating materials were developed in an attempt to solve this challenge.

The intersection of the exterior wall and the floor assembly provides a number of different paths that may allow a fire to spread. Each of these paths is addressed by different test standards. The International Building Code (IBC) and NFPA codes establish different requirements for each potential path and addresses the means to protect the paths or to prevent the spread of fire based on each separate one.

As with all joint firestops, the intent is to confine a fire to the room of origin and prevent propagation through the floor, ceiling, or walls. With ineffective curtain wall and perimeter void fire protection, fire can spread through the space between floors and walls, through the window head transom and the cavity of the curtain wall, or through broken glass or melted aluminum spandrel panels.

Conceptually, the easiest way to look at the three paths for the fire to spread to adjacent floor levels at the exterior wall is:

- through the void spaces created between the edge of the floor and an exterior curtain wall—these are protected by perimeter fire barrier systems per ASTM E2307, Standard Test Method for Determining Fire Resistance of Perimeter Fire Barriers Using Intermediate-scale, Multi-story Test Apparatus, and ASTM E2393, Standard Practice for Onsite Inspection of Installed Fire-resistive Joint Systems and Perimeter Fire Barriers;

- via the voids or cavities within the exterior curtain wall, with fire spreading by a path within the concealed space of the exterior wall, or along the outer surface of the exterior wall—these are protected by assemblies compliant with NFPA 285, Standard Fire Test Method for Evaluation of Fire Propagation Characteristics of Exterior Non-loadbearing Wall Assemblies Containing Combustible Components; and

- by leapfrogging (i.e. spreading to the exterior and then impinging on an opening in an upper level)—this mechanism is currently addressed prescriptively, using spandrel panels or sprinkler protection, with a new ASTM test method still under development.

The perimeter fire barrier system is a unique building construction detail installed to protect against the passage of fire, hot gases, and toxic smoke through the voids between the floor slab edge and a nonrated exterior wall (usually a curtain wall). Perimeter fire barrier systems are used to resist interior propagation of fire through the gap between floor and exterior wall for a period equal to the floor’s fire-resistance rating. Additionally, a building’s perimeter fire barrier system should accommodate various movements, such as those induced by thermal differentials, seismicity, and wind loads.

[3]

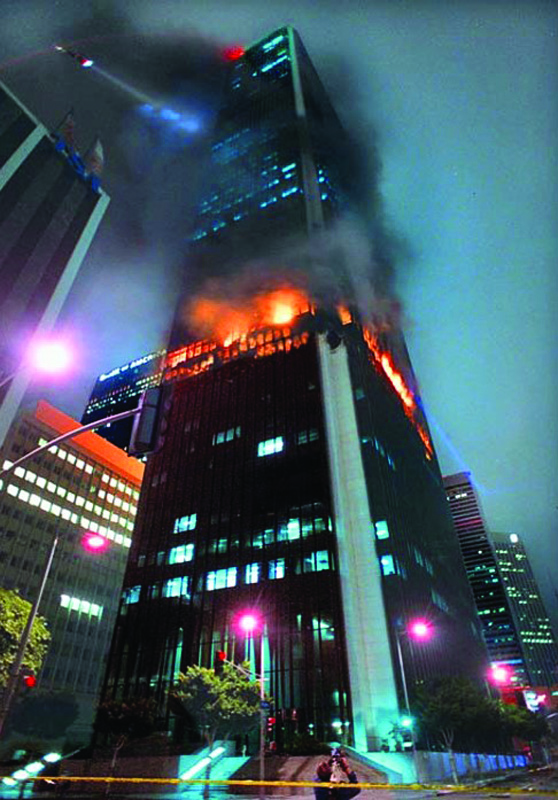

[3]History of perimeter containment failures

There have been multiple cases showing what kind of damage can be done when fires move through improperly protected concealed spaces. In 1988, the 62-story Los Angeles tower, First Interstate Bank building, caught fire on its 12th floor. The fire spread to the 16th floor on the building after the combustibles in work stations ignited and rapidly grew. The exterior glass panels began to break, providing both additional oxygen and an alternate path for the fire to travel.

Flames spread through the gap in the joint between the floor/ceiling slab and the curtain wall. The fire vented through broken windows, first preheating combustibles on floors above before eventually igniting their contents. The building was being retrofitted with sprinklers at the time, but the system was not operational, so the fire was free to spread and grow. The fire was finally contained by firefighters after 3.5 hours.

On February 12, 2005, a fire started on the 21st floor of the Windsor Tower or Torre Windsor (officially known as Edificio Windsor) in Madrid, Spain. The building was a 32-story concrete building with a reinforced concrete central core. It was not sprinklered, and had been undergoing progressive refurbishment over a three-year period. The fire burned for 20 hours, spreading to all levels above the second floor.

At the time of construction, the Spanish building code did not require perimeter firestopping or perimeter columns and internal steel beams to be fire-protected. As a result, the original existing steelwork was left unprotected and the gap between the original cladding and floor slabs was not firestopped. In fact, these weak links in the fire protection of the building were being rectified in the refurbishment project at the time of the fire. Since the building adopted the ‘open-plan’ floor concept, effectively, the fire compartmentation could only be floor-by-floor (about 40 x 25 m [131 x 82 ft]). However, the lack of perimeter fire barriers in floor openings and between the original cladding and the floor slabs led to a failure of the vertical compartmentation, and the complete collapse of the building.

[4]

[4]The challenges

A curtain-wall-clad building is a multistory structure having exterior walls not part of the loadbearing structure. As floor slabs are supported by interior beams and columns, there is a perimeter void or gap, typically ranging from 25 to 200 mm (1 to 8 in.), between each floor slab and the exterior curtain wall. Outside walls may be constructed using one of several materials, including glazing, light-gage metals, and gypsum wallboard.

The performance of a curtain wall during a building fire, or fire test, depends on the assembly being installed, but nonrated wall system performance significantly varies. Perimeter voids are generally hidden from view after construction. Once installed, these construction gaps are rarely inspected or re-evaluated unless renovations are made. They must be sealed to prevent spread of flames, smoke, and toxic gases in the event of a fire.

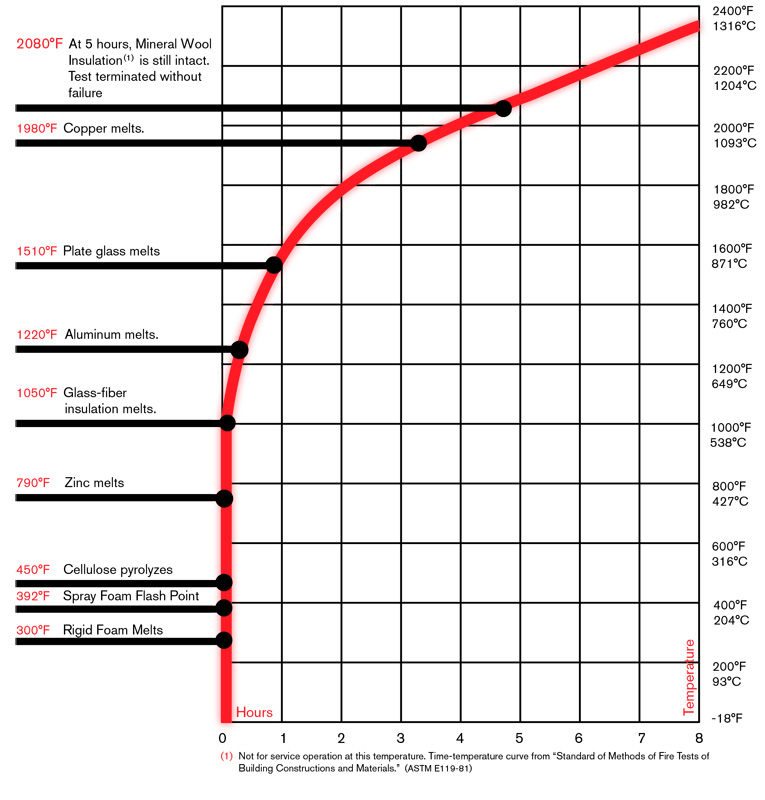

As mentioned, the intent with joint and perimeter firestopping is to confine a fire in the room of origin, preventing its propagation through the floor, ceiling, or walls. Mineral wool, with its high melting temperature, noncombustibility, and ability to retain its strength and integrity under fire conditions, is suited to protecting openings between fire-rated floors and rated or nonrated exterior wall assemblies. (For more, see “Why Mineral Wool?,” below.)

Some insulation materials, such as foamed plastics, melt or burn at levels far below the potential temperature of a structure fire. Flames inside a building can melt aluminum and copper, and cause steel studs and panels to buckle. The loss of these structural elements allows fire to escape quickly up the outside walls. Properly installed perimeter fire barrier systems, using mineral wool insulation, have demonstrated their ability to remain in place longer, and can prevent the passage of flame and hot gases between adjacent stories of a building.

Real fire experience has shown when there is ineffective curtain wall and perimeter void protection, a fire can spread through the space between floors and walls, and the window head transom and the cavity of the curtain wall, as well as through broken glass or around melted aluminum spandrel panels.

As a result, work began on the development of materials and systems to prevent fires from spreading through unprotected joints around the perimeter of floors. Part of the subsequent success of high-rise buildings is due to their perimeter fire containment systems. At every location where two components (e.g. steel beams or floor slabs) are located, mineral wool installed as a part of perimeter fire barrier systems is the key contributor that provides the critical fire containment.

| WHY MINERAL WOOL? |

| Due to the challenging nature of perimeter fire containment, mineral wool is suited to provide the necessary fire safety performance in fires. This form of manufactured vitreous fiber was initially developed in the mid-1800s by melting slag and spinning it into insulation for use in homes and industry. The term ‘mineral wool’ actually encompasses two products—rock wool and slag wool—that employ different raw materials in their manufacture. Rock wool is made from natural rocks like basalt or diabase, while slag wool is made primarily from iron ore blast furnace slag.

Production begins when natural rock or iron ore blast furnace slag is melted in a cupola furnace or pot. Once melted, this hot, viscous material is poured in a narrow stream onto one or more rapidly spinning wheels, which cast off droplets of molten material and creates fibers. As the material fiberizes, its surface may be coated with a binder material and/or de-dusting agent (e.g. mineral oil). The fiber then is collected and formed into batts or blankets for use as insulation, or baled for use in other products, such as acoustical ceiling tile, spray-applied fireproofing, and acoustical materials. Key points in the manufacturing process include:

Products made from rock and slag wool are extremely useful. They are noncombustible and do not support the growth of mildew and mold when tested in accordance with ASTM C665, Standard Specification for Mineral-fiber Blanket Thermal Insulation for Light-frame Construction and Manufactured Housing. Rock and slag wool fibers also are dimensionally stable and have high tensile strength. In addition to providing insulation, they absorb sound and, with a vapor retarder, help control condensation. The physical and chemical properties of rock and slag wool are major factors in their utility. As the fibers are noncombustible and have melting temperatures in excess of 1090 C (2000 F), they are used to prevent the spread of fire. As a primary constituent of ceiling tiles and sprayed fireproofing, rock and slag wool provide fire protection as well as sound control and attenuation. The excellent thermal resistance of these wools is also a major factor in their use as commercial insulation, pipe and process insulation, insulation for ships, domestic cooking appliances, and a wide variety of other applications. |

[5]

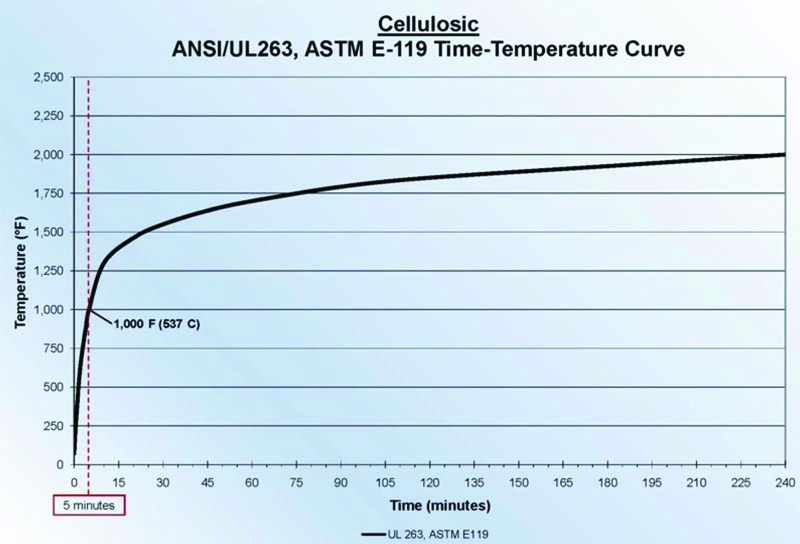

[5]Evolution of ASTM E2307

Curtain wall design became common in commercial construction over the past 40 years, but there were no consensus fire test standards or testing procedures for fire protection of exterior curtain walls and floor-to-wall perimeter voids until 2004. The legacy model codes included only cursory mention of this building issue, so architects, designers, contractors, and code officials often adopted untested and uncertain solutions. Later, more effective products were developed and tested for curtain wall fire protection in accordance with ASTM E119, Standard Test Methods for Fire Tests of Building Construction and Materials. However, because that standard does not specifically address these unique construction joints, codes only partially addressed the fire risk.

In 2004, ASTM E2307 was developed. Evaluating the interface between a fire-resistance-rated horizontal assembly and an exterior curtain wall, this test method is used to measure and describe the response of materials, products,

or assemblies to heat and flame under controlled conditions. However, it does not by itself incorporate all factors required for the fire-hazard or fire-risk assessment of the materials, products, or assemblies under actual fire conditions, using a test structure called the Intermediate-scale, Multi-story Test Apparatus (ISMA).

The ISMA test simulates fire exposure in a high-rise structure where, as the fire intensifies and positive pressure builds, a fire-induced window break occurs, allowing oxygen to feed the flames. The method is meant to simulate a fire in a post-flashover condition in a compartment venting to the exterior.

The provisions of ASTM E2307 are intended to restrict the interior vertical passage of flame and hot gases from one floor to another at the location where the floor intersects the exterior wall assembly. Its use is mandated by U.S. building codes, thereby requiring the protection of openings between a floor and an exterior wall assembly to provide the same fire performance as that required for the floor.

U.S. building codes

Since their 2006 editions, both IBC and NFPA 5000, Building Construction and Safety Code, have referenced ASTM E2307 as a means of providing perimeter fire barrier joint protection installed in the space between an exterior wall assembly and a floor assembly. The 2015 IBC Section 715.4 requires where fire-resistance-rated floor or floor/ceiling assemblies are installed, voids that are created at the intersection of the exterior curtain wall assemblies and the floor assemblies be sealed with an approved system to prevent the interior spread of fire. It further requires those systems be tested in accordance with ASTM E2307 to provide an F rating for a period not less than the fire-resistance rating of the floor assembly.

[6]

[6]A notable exception to the IBC requirement for ASTM E2307 is for glass curtain wall assemblies, when the vision glass extends to the finished floor level (i.e. full-height glass). In those cases, IBC alternatively permits the perimeter void to be protected with an approved material capable of preventing the passage of flame and hot gases sufficient to ignite cotton waste where subjected to ASTM E119 time-temperature fire conditions for the same duration as the fire-resistance rating of the floor assembly.

Where the joint between walls involves a non-fire-resistance-rated floor and an exterior curtain wall, there is no reason to try to maintain a fire-resistance rating with a rated joint system. However, spread of smoke is a concern, and, therefore, the code calls for a tight joint to protect the rapid spread of smoke from a floor of fire origin to other floors of the building. Consequently, IBC and NFPA 5000 still require where a fire-resistance-rated floor intersects with a nonrated spandrel wall, the void space must be protected by an approved joint system.

[7]

[7]Five keys to effective perimeter fire barriers

Joint systems and perimeter fire barrier systems are important elements for designers, specifiers, installers, and inspectors. These five key elements provide

a simple process for a team to follow to ensure a perimeter fire barrier system is properly designed and installed.

1. Know what your local code requires.

Perhaps obvious, but this is a critical first step occasionally overlooked.

2. Specify to meet code requirements.

Once you understand the code, you can select the right products and systems. This begins by understanding the nuances of the ratings reported on labels and the manufacturer’s literature.

3. Avoid improper substitutions.

This starts with the specification, but often comes down to the general contractor ensuring there are no inappropriate substitutions on the jobsite that run contrary to the spec and, ultimately, code. For example, spray or board foam cannot be used in place of mineral wool in a perimeter fire barrier system.

4. Install it right.

It is important to understand a building’s perimeter containment system is not a single material, but rather, comprises the exterior curtain wall and the glazing, which is designed to impede the vertical spread of fire to higher floors from the room of origin in high-rise buildings. The void created between a floor and a curtain wall can range anywhere between 25 and 305 mm (1 and 12 in.) or more, which clearly requires sealing to prevent the spread of flames and products of combustion between adjacent stories.

The width of the joint, which has maximum allowable dimensions specified in the perimeter fire barrier system listings, is the distance between the edge of the framing nearest the floor and the adjacent floor edge. The void space or cavity between framing members is not considered joint space.

5. Verify the installation was done right.

Quality assurance is critical—so much so, recent editions of codes make special inspection a requirement, as discussed later in this article.

The term ‘perimeter fire barrier system’ refers to the assembly of materials preventing the passage of flame and hot gases at the void space between the interior surface of the wall assembly and the adjacent edge of the floor. For the purposes of ASTM E2307, the interior face is at the interior surface of the wall’s framework. Tested and listed perimeter fire barrier systems do not include the interior finished wall (e.g. knee wall) details. This makes the systems applicable to any and all finished wall configurations. The existence of the interior wall, even if made of fire-resistant materials (e.g. fire-resistance-rated gypsum board), does not eliminate the need to have an appropriately tested material or system to protect the curtain wall from interior fire spread at the perimeter gap—unless that interior wall detail has been specifically tested and shown to meet the requirements of this code section.

[8]

[8]Five rules of perimeter fire barriers

There are five basic design principles for installation of successful perimeter fire containment.

1. Install a reinforcement member or a stiffener at the safe-off area behind the spandrel insulation.

This practice prevents bowing otherwise caused by the compression-fit of the insulation.

2. Use mechanical attachments for the mineral wool spandrel insulation—adhesives and friction-fit applications do not work.

The adhesive service temperature ranges from −34 to 120 C (−30 to 250 F). Fire exposure temperatures based on ASTM E119 very quickly exceed the adhesive service temperatures, resulting in failure of the adhesive-applied attachment to hold the spandrel insulation in place.

3. Protect the mullions by using mineral wool mullion covers.

Aluminum begins to melt at 660 C (1220 F). Without the mullion protection on the fire exposure side, the aluminum mullions and transoms soften and melt. The mechanical attachments holding the mineral wool spandrel insulation will no longer be in place, allowing the spandrel and insulation to fall out. This can result in a breach of flame and hot gases to the floor above.

4. Ensure the insulation is compression-fit (typically 25 percent, but varies by system) between the slab edge and the inside face of the spandrel insulation.

This compression-fitting of the insulation creates a seal that maintains its integrity preventing flame and hot gases from breaching through to the floor above.

5. Apply an approved smoke sealant material to the top of the insulation to provide a smoke barrier to the system.

The smoke seal is commonly spray-applied to the top of the insulation (non-fire-exposure side) forming a smoke barrier with a typical leakage rating (i.e. L rating) of 0. In addition, a 25-mm (1-in.) over-spray—as specified—onto the floor slab and spandrel insulation creates a continuous bond that adds to holding the perimeter insulation material in place during the fire and building movement.

[9]

[9]Field inspection and enforcement

While proper design and testing of perimeter fire barrier joints is critical, poor installation and maintenance can lead to unacceptable real-world performance in fires. To help alleviate this, ASTM E2393 was first published in 2004. This practice covers the procedures to inspect fire-resistive joint and perimeter fire barrier systems, including methods for field verification and inspection. This standard practice provides methods by which qualified inspectors verify required fire-resistive joint systems on a project have been installed in accordance with the inspection documents.

Adoption and use of ASTM E2393 has been growing across the United States in recent years. In fact, since the publication of the 2012 IBC, “special inspection” is required for perimeter fire barrier systems installed in high-rise buildings, or in buildings assigned to Risk Category III or IV. Special inspection includes monitoring of materials, installation, fabrication, erection, and placement of components and connections that both require special expertise and are critical to the integrity of the building structure. Special inspections are supplemental to the typical municipal inspections required by the building department specified in IBC. Special inspectors monitor the materials as well as the workmanship critical to the structural and fire-resistive integrity of a given building, and bring technical expertise to the job that is not typically available in local government.

IBC clearly identifies situations in which the employment of special inspectors or special inspection agencies is mandatory. In those cases, the use of special inspectors and special inspection agencies is not discretionary.

Conclusion

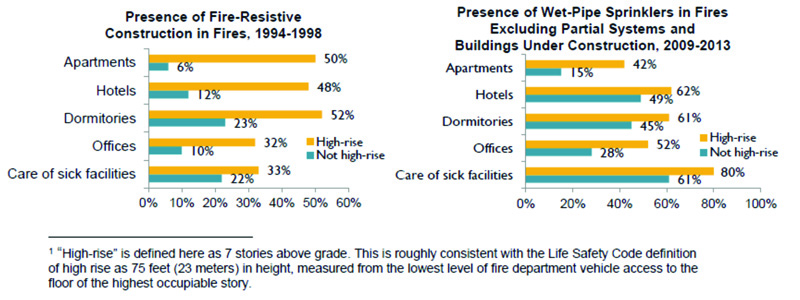

The importance of balanced fire protection cannot be sufficiently stressed. The fire death rate per 1000 fires and average loss per fire are generally lower in high-rise buildings than in other buildings of the same property use. This is because high-rises are more likely to have fire-resistive construction and wet pipe sprinklers.

Perimeter fire barrier systems are an important part of effective fire-resistance-rated and smoke-resistant compartmentation systems. They have been developed for fire and life safety protection at the important curtain wall gap.

Neglecting the curtain wall/floor void means compromising the safety of people in the building. When floors are required by codes to have a fire-resistance rating, this comes with a financial cost. Improper installation or design of perimeter joint protection not only compromises fire safety, but also negates some of the building fire protection performance for which owners are paying.

Mineral wool is suited to provide the necessary fire safety performance. Its high melting temperature, coupled with dimensional stability and high tensile strength, provides the resistance needed for these critical applications. Perimeter fire barrier systems provide designs capable of maintaining continuity of the fire-resistance-rated floor to the exterior edge of the building for both rated and nonrated exterior walls. This provides vertical compartmentation for the potentially large gap areas at the edge of floor slabs, to prevent fire from spreading vertically.

Ultimately, proper execution of perimeter fire barrier systems requires collaboration between architects, specifiers, general contractors, installers, and inspectors. They need to design it according to code, specify it correctly, critically evaluate substitutions, and then install it properly.

Tony Crimi, P.Eng., MASc., is a registered professional engineer and founder of A.C. Consulting Solutions Inc., specializing in building- and fire-related codes, standards, and product development activities in the United States, Canada, and Europe. Working with manufacturers and industry associations, he advocates for approval and safe use of materials and products, and for their code recognition. Crimi has more than three decades of experience in the area of codes, standards, testing, and conformity assessment. He is an active participant in International Code Council (ICC), National Fire Protection Association (NFPA), ASTM, UL, and ISO, and is the immediate past-chair of the National Building Code of Canada (NBC) Standing Committee on Fire Protection. Crimi can be reached at tcrimi@sympatico.ca[10].

- [Image]: https://www.constructionspecifier.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/09/Curtain-Wall-Test.jpg

- www.nfpa.org/news-and-research/fire-statistics-and-reports/fire-statistics/fires-by-property-type/high-rise-building-fires: http://www.nfpa.org/news-and-research/fire-statistics-and-reports/fire-statistics/fires-by-property-type/high-rise-building-fires

- [Image]: https://www.constructionspecifier.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/09/3D-Curtain-Wall-Illustration.jpg

- [Image]: https://www.constructionspecifier.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/09/First-Interstate-Bank-Fire-1988.jpg

- [Image]: https://www.constructionspecifier.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/09/ASTM-E-119-Time-Temp-Curve.jpg

- [Image]: https://www.constructionspecifier.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/09/Cellulosic-TimeTempCurve_Graph.jpg

- [Image]: https://www.constructionspecifier.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/09/Madrid-Fire-2005_2.jpg

- [Image]: https://www.constructionspecifier.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/09/Fire_ComparisonBarCart.jpg

- [Image]: https://www.constructionspecifier.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/09/Fire-Barrier-Paths-of-Fire-Spread.jpg

- tcrimi@sympatico.ca: mailto:tcrimi@sympatico.ca

Source URL: https://www.constructionspecifier.com/perimeter-fire-barrier-systems-taking-a-team-approach-to-fire-safe-construction/