Polished concrete: Not just shiny

by nithya_caleb | February 5, 2020 12:00 am

[1]

[1] [2]SPECIFICATIONS

[2]SPECIFICATIONS

by Chris Bennett, CSI, and Keith Robinson, RSW, FCSC, FCSI

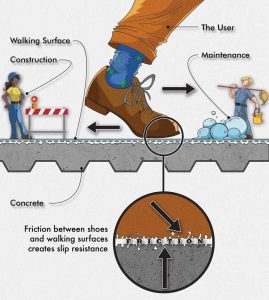

Designers specify polished concrete floors because they are durable and easy to maintain. They also reduce material use because existing slabs, or purpose-made slabs, can be employed to create a final floor finish. Additionally, polished concrete has a broad aesthetic range. Color can be selected through the use of pigments, dyes, acid stains, or even sand and aggregate choice. Aggregates can be exposed to different levels. Special aggregates such as marble chips and colored glass could also be added. The reflective characteristics of a polished concrete floor can be expressed from low-sheen matte to high-gloss, mirror-like reflective finishes. It is also straightforward to specify slip resistance using quantifiable coefficient of friction (COF) values and testing procedures. Unfortunately, many of the benchmarks used to specify and build polished concrete floors focus on aesthetics alone, leaving durability, sustainability, and COF unanswered.

Polished concrete’s popularity has increased in the last 15 years. Despite this growing demand, the industry has not been able to standardize the language to describe durable, safe, and attractive concrete floors. During polished concrete’s infancy, specifiers, designers, and owners turned to contractor terms like grit to help them establish a baseline without fully appreciating the variety of solutions this word represents, and opened themselves up to undefinable benchmarks.

[3]

[3]Use of contractor terms

Grit describes the abrasive size of industrial diamonds in the matrix of grinding and polishing pads used to polish concrete. It helps craftspersons select tooling choice for the refinement steps they are working on, and navigate the execution of a polished concrete floor. However, it does not communicate the design outcome by using a qualitative approach. Though grit sizes are fairly universal, abrasive grains can vary from metal chaff to industrial diamond and other materials. There can be pure mixtures of abrasive grains of only one size or the matrix of the polishing puck (often called a diamond tool) can contain variable dimensions to create an average size. The size and shape of the polishing puck also affects outcomes on

[4]

[4]Image © A New Concrete Glossary, created by Mike Smith and Kathryn Marek

the floor, delivering different scratch patterns and refinement levels. As concrete varies in hardness, so do the diamond polishing pucks. An individual manufacturer can produce a variety of abrasive tools within a specific grit category. In other words, a company could offer multiple types of abrasive tools varying in size, shape, and matrix material (all with different scratch patterns), and yet designate them with an identical grit number. Unless one is truly skilled in the trade and understands the thousands of differences that the word grit could represent, the specifier is in unfamiliar territory that will quickly land him/her in a means and methods quagmire.

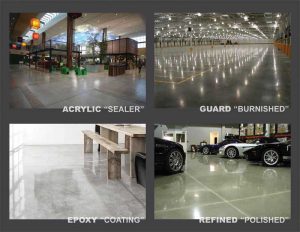

There are other problems with using the word grit that may not be readily considered. Grit also describes the size of abrasive grains on janitorial buffing and burnishing pads, opening up even more variables to this word. These types of pads can be used with topical solutions that can become shiny through burnishing. Instead of a polished concrete floor, a client can unknowingly be handed a coated shiny doppelgänger lacking durability and quantifiable COF. Further, some styles of epoxy resin coatings are sold in solid form as diamond tools containing abrasive grains. These, therefore, carry a grit designation (i.e. 400, 800, etc.) However, what actually happens with these types of products is that they are super-heated under the weight of commercial grinders. The high-speed revolutions of the grinding cause the epoxy to melt and become smeared across the concrete and leave the floors with a shiny coat through resin transfer.

Defining polished concrete

[5]

[5]Image © Concrete Intelligence Agency

Specifiers are not the only ones affected in this seemingly confusing world of attempting to quantify polished concrete. In attempts to gain flooring market share, many coating companies joined trade organizations and relevant committees to lobby for the expansion of the definition of polished concrete to include all materials that could make a floor shiny. As an example, the current definition of polished concrete, according to the Concrete Polishing Council (CPC) and the American Society of Concrete Contractors (ASCC) is, “Polished concrete is the act of changing a concrete floor surface, with or without aggregate exposure, to achieve a specified level of gloss using one of the listed classifications—bonded abrasive polished concrete, burnished polished concrete, or hybrid polished concrete.”

It is not that they have ruled out polished concrete created through refinement of the material itself, but they have also included liquid-applied coatings and classified it all as “polished concrete.” As the character Inigo Montoya famously said in William Goldman’s the Princess Bride, “You keep using that word. I do not think it means what you think it means.”

The preferred method to quantify polished concrete from CPC and other groups is again limited to gloss and reflectivity—this misses the qualitative attributes necessary to provide full performance criteria relating to the floor’s use. As an example, groups will use reflectivity as a benchmark via distinctness of image (DOI) gloss. DOI is an aspect of gloss characterized by the sharpness of images of objects produced by reflection at a surface, per ASTM E284, Standard Terminology of Appearance. This is helpful to describe the aesthetic appearance, and has been used in the automobile coating industry to define reflective car coat quality for some time—hence, the attempts to use similar benchmarks for polished concrete.

The devices used to carry out these tasks are called gloss meters, with the degrees of radiant light measured in lumens (lm). These tools are useful for various applications and are accurate for reporting the amount of gloss reflected (or light quality) off the floor, but they do not remotely begin to tell how the light is reflected. Was the concrete properly refined, meaning is the finished surface durable, sustainable, and enjoying some measure of COF? Or did a resinous coating product from Division 09 get installed, and will not be discovered as an apparent substitution until the floor fails?

[6]

[6]Image © Chris Bennett, Bill DuBois, John Guill, and Keith Robinson

Over the past decade, building professionals have been working hard to create testing methodologies that are easy, repeatable, and speak to physically making concrete slabs tough as well as shiny and beautiful. Bruce Nicholson, one of the earliest polishing contractors in North America, along with the late Harry Gressette, were some of the first, skilled tradespersons to begin measuring the floor itself and not just reflected light. Along with craft persons like Chris Swanson and pioneering architectural firms like DIALOG, Laith Sayigh’s DFA, Johnson McAdams Group, Gensler, SRG Partnership, and Thrailkill Associates, empirical research at the University of Alberta, Alberta, Canada, and the University of Akron, Ohio, and training events around North America began to prove through millions of square feet benchmarks for polished concrete can be quantified by readings taken from the concrete micro-surface texture with simple stylus devices (e.g. profilometers), while mechanically processing a floor to achieve a surface with high physical durability and chemical and stain resistance within an aesthetic framework. However, despite the evidence supporting using quantifiable and qualitative methods like measuring micro-surface texture there is yet to be an accepted standard for project team members to clearly communicate definitions and check polished concrete benchmarks.

The Concrete Sawing and Drilling Association (CSDA) published the first standard known as ST 115, Measuring Concrete Micro Surface Texture, to measure concrete surfaces and their surface texture value to evaluate how the concrete itself (versus mere reflected light) influenced the finishing process with regards to gloss, friction, and sustainability. It was an amazing success when compared to previous standards from the Concrete Polishing Association (CPAA) and similar groups where gloss considerations were used for benchmarks. However, due to ST 115’s attempt to create a micro-surface texture grade scale that equaled an approximate ‘grit scale,’ this well-intentioned standard was unable to achieve a clear path on a methodology to achieve consistent roughness average (Ra) readings and measure accordingly.

The National Center for Education and Research on Corrosion and Materials Performance (NCERCAMP) at the University of Akron continues the study of polished concrete, abrasion resistance, COF, and even the installation and maintenance of carbon footprint for this floor finish. In April 2020, it will host the third annual National Concrete and Corrosion Symposium in partnership with Kent State University, Ohio, as well as other schools and organizations to further research. Additionally, the National Concrete and Corrosion Symposium Research Fund has been created to allow owners, architects, academia, constructors, and manufacturer team members to participate and help develop a standard and installation curriculum that can be utilized to define quantifiably, not only what is to be achieved as a condition of the construction documents, but also how to do so with the goal of aiding design professionals reach net-zero emissions in their projects.

Conclusion

[7]

[7]Photos courtesy XRQ Corp

Liquid-applied ‘doping-agents’ and ‘finishing enhancers’ that are used to manage the grinding and polishing process suffer from the same contractor-derived meanings as grits. They are helpful for describing the process, but not for illustrating the qualitative slab properties, such as stain resistance, water repellency, or COF, a design professional wants to achieve. Each of these properties could require different liquid-applied products or grit profiles. Specifications describing ‘sealers’ or ‘densifiers,’ in general terms, cannot fully provide the required performance values to explain the required degree of stain resistance. A performance requirement must describe what stains the finish is required to resist, be that orange juice, ketchup, and mustard, wine and beer, or animal byproducts, as all of these may require a different doping-agent or combination of sealers and densifiers to achieve the expected performance.

Simply stating constructor terms has done a disservice to the industry as a whole by trying to market various doping-agents into niche categories. Very few people are able to determine the difference between the sealers and physically refined polished floors. Stating the use of the different doping-agents without mentioning the performance expectations can lead the contractor to propose substitutions. Only few specifiers can determine potential differences, and only after floor performance is affected.

The lack of standardized terminology results in bids, including fully refined, ground, and polished concrete floors as well as surface-applied sealers or coatings. Using contractor terminology to build a means and methods specification always backfires, and the nature of the language leaves the design firm and owner at risk for poor outcomes.

Specifications with micro-surface benchmarks measured in microinches (μin) or micrometers (μm) as a means to describe surface profile and COF combined with distinctiveness of image to confirm the aesthetic appearance can successfully describe performance criteria without relying on application of resinous coatings or topical sealers.

Chris Bennett, CSI, is the owner of Bennett Build, a network of construction professionals and researchers dedicated to helping organizations understand and solve concrete and flooring problems. He can be reached via e-mail at chris@bennettbuild.us[8].

Keith Robinson, RSW, FCSC, FCSI, is an associate at Dialog in Edmonton, Alberta. Robinson also instructs courses for the University of Alberta, acts as an advisor to several construction groups, and sits on many standards review committees for ASTM and the National Fire Protection Association (NFPA). He can be reached at krobinson@dialogdesign.ca[9].

- [Image]: https://www.constructionspecifier.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/Instagram-2.jpg

- [Image]: https://www.constructionspecifier.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/Keith-Robinson-2.jpg

- [Image]: https://www.constructionspecifier.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/Photo-Aug-15-10-10-05-AM.jpg

- [Image]: https://www.constructionspecifier.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/00-Friction-Illustration-F-R-1.jpg

- [Image]: https://www.constructionspecifier.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/image0.jpg

- [Image]: https://www.constructionspecifier.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/meter.jpg

- [Image]: https://www.constructionspecifier.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/CONCRETE-SURFACE-TREATMENT-TYPE-CB-2.jpg

- chris@bennettbuild.us: mailto:chris@bennettbuild.us

- krobinson@dialogdesign.ca: mailto:krobinson@dialogdesign.ca

Source URL: https://www.constructionspecifier.com/polished-concrete-not-just-shiny/