Preserving architectural treasures in New York’s historic districts

by sadia_badhon | December 21, 2018 10:55 am

by Jennifer Gleisberg, CDT

[1]

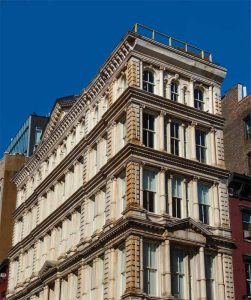

[1]With the world’s largest concentration of full and partial cast-iron buildings, New York City’s NoHo and SoHo neighborhoods are treasure troves of historically significant architecture[2] built during the second half of the 19th century.

The significance of cast-iron architecture has been recognized by the New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission (LPC), as the NoHo and SoHo neighborhoods have been certified local historic districts. The NoHo area received landmark designation in 1999 that was extended in 2008, while SoHo was designated a historic district in 1973 and extended in 2010.

Cast-iron façades consist of thousands of pieces prefabricated in foundries using molds and held together by clips, angles, and mechanical fasteners. According to LPC, cast-iron architecture from the mid- to late-1800s offered several attributes New York businesses found attractive.

“A cast-iron structure was easy and quick to erect in comparison with a masonry[3] building, and it was also cheaper,” the commission reported. “Essentially, the pieces were an early form of prefabrication; they were cast in multiple units that could be readily combined and assembled in numerous ways. Naturally, this was much cheaper than carving each piece individually in stone.”

Finished façades imitated classical French and Italian architectural designs and were often painted to resemble sandstone, limestone, or even marble.

“When faced with a limited budget, an owner far preferred an elaborate cast-iron façade[4] reflecting the grandeur of Paris or Venice than a simple masonry wall,” the commission said.

[5]

[5]Guidelines and standards governing New York’s historic districts protect cast-iron structures from demolition, structural alterations, or exterior changes, while also emphasizing the importance of preserving and maintaining landmark buildings from deterioration.

Maintenance and repair techniques for restoring severely rusted or damaged cast-iron[6] façades were presented in a National Park Service (NPS) preservation brief prepared in cooperation with the New York Landmarks Conservancy. The brief was prepared by John G. Waite, FAIA, a former senior historical architect for the New York State Office of Parks, Recreation and Historic Preservation and senior principal at John G. Waite Associates, Architects PLLC.

“The successful conservation of cast-iron[6] architectural elements and objects is dependent upon an accurate diagnosis of their condition and the problems affecting them, as well as the selection of appropriate repair, cleaning, and painting procedures,” Waite explained. “Frequently, it is necessary to undertake major repairs to individual elements and assemblies; in some cases, badly damaged or missing components must be replicated.”

[7]

[7]Waite offered the following suggestions when assessing the condition of cast-iron façades:

- erect scaffolding or use a mechanical lift to carefully inspect every section of iron construction, including bolts, fasteners, and brackets;

- remove paint to determine the condition of connections, metal fasteners, and intersections of crevices where moisture can collect; and

- establish whether loadbearing columns and beams are performing in accordance with their original design[8], or if stress patterns have changed.

If extensive damage to the cast iron is present, it is best to secure the services of an architect or conservator specializing in historic buildings, recommended Waite.

A critical part of the cast-iron restoration process involves the application of high-performance coatings like those specified for the award-winning 54 Bond Street building in New York’s NoHo Historic District and the 77 Mercer Street condominium in SoHo.

Bond Street building

Constructed in 1874, the 1394-m2 (15,000-sf) building on 54 Bond Street started as a bank and was later used for storage space and as a theater. In 2007, the six-story building was converted into a condominium property occupied by commercial spaces on its first two floors and high-end residential lofts on the upper levels. It is currently owned by the 54 Bond Street Condominium.

[9]Designed by Henry Engelbert in elegant French Second Empire style, the building was designated a New York City landmark in 1967 by LPC and was listed on the National Register of Historic Places[10] (NRHP) in 1980.

[9]Designed by Henry Engelbert in elegant French Second Empire style, the building was designated a New York City landmark in 1967 by LPC and was listed on the National Register of Historic Places[10] (NRHP) in 1980.

Despite its architectural pedigree, time took its toll on the structure’s cast-iron exterior, leaving it heavily rusted, leaking, and in need of a major restoration.

In 2011, New York-based CTA Architects P.C. was contracted by the building’s owner to restore the cast-iron façade to its original condition, address severe leakage issues, and perform construction project administration services.

Throughout the restoration of 54 Bond Street, CTA worked with LPC. The commission approved all processes, materials, and equipment, including the security cameras installed on the building. CTA specified cameras that were installed using a low profile to not detract from the building’s aesthetics.

After successful completion of the restoration in 2017, the cast-iron project received the New York Landmarks Conservancy’s highest honor for preservation, the Lucy G. Moses Preservation Award in 2018.

[11]Early work on the $4.5-million project involved detailed documentation of the façade’s condition by CTA project manager Matthew Jenkins, AIA, who is experienced in cast-iron restorations. Jenkins is a member of the Association for Preservation Technology International (APT) and the Society of Architectural Historians (SAH). He also serves as an advisor to the Historic District Council (HDC) in New York and is an adjunct lecturing professor at New York City College of Technology–City University of New York.

[11]Early work on the $4.5-million project involved detailed documentation of the façade’s condition by CTA project manager Matthew Jenkins, AIA, who is experienced in cast-iron restorations. Jenkins is a member of the Association for Preservation Technology International (APT) and the Society of Architectural Historians (SAH). He also serves as an advisor to the Historic District Council (HDC) in New York and is an adjunct lecturing professor at New York City College of Technology–City University of New York.

The 54 Bond Street façade was unique in terms of its size, corner location, and the volume of ornamental cast-iron components. This resulted in a more extensive project. Jenkins estimated only a handful of cast-iron buildings in Manhattan have two façades.

[12]

[12]Jenkins spent long days working from a boom truck to assess the extent of damage to the façade’s ornamental cast-iron components, ranging in size from 102 x 102 mm (4 x 4 in.) to 2 m (6 ft) long x 508 mm (20 in.) wide.

“Seventy-five percent of the cast iron was removed from the building completely,” Jenkins recalled. “We examined both the inside and outside of each piece that came off the building for rust and deterioration to determine how many pieces needed to be replaced and which required casting new pieces. With cast iron, the foundry can make molds from original pieces. This ensures the replicated units are the exact same size as the originals.”

Cast-iron pieces to be replaced were numbered and shipped to a foundry in Ghent, Belgium. There, 164 molds were created and used to replicate 2890 cast-iron components. The components were then shipped to the jobsite in New York for assembly and installation. Special care was taken to avoid the use of alternate materials from those found on the original building façade.

[13]

[13]Given the building’s landmark status, CTA placed a high priority on preserving as much original material as possible, Jenkins noted. Stripper tape containing a solvent was used to remove old paint from original cast-iron pieces found to be in good condition, which would remain attached to the façade. This method prevented dust from drifting onto adjacent properties.

Jenkins’ inspection included the façade’s cast-iron water tables running the length of the building between each floor, a sheet metal cornice at the top of the structure, and three exterior stairways leading to residential and retail entrances.

Resembling decorative cornices, the water tables serve dual purposes as a design element and to prevent water from running down the face of the building. The tops of all the water tables, where rainwater pooled, were replaced with new cast iron, molded to fit perfectly.

The deteriorated sheet-metal cornice and structural supports located at the top of the building were replaced with an exact replica fabricated in Long Island City.

Jenkins discovered the original cast-iron stairways concealed underneath diamond plate sheet metal shells installed by a former owner. New stairs and balusters were constructed to match the originals found in old photographs and from remnants that survived more than a century of heavy use and weathering.

Collaboration between Jenkins and the project’s coatings consultant Phil Gonnella involved testing the adhesion and performance of a water-based, low-odor protective coating system with minimal levels of volatile organic compounds (VOCs). The odor control was an important element because the residences in the building were occupied.

| PAINT REMOVAL AND APPLICATION |

| In his National Park Service (NPS) preservation brief, “The Maintenance and Repair of Architectural Cast Iron,” author John G. Waite, AIA, discusses several techniques for removing old paint and corrosion from architectural cast iron, including wire brushing, sandblasting, flame cleaning, and the use of chemical methods such as acid pickling.*

According to Waite, selecting the appropriate technique depends on how much paint failure and corrosion has occurred as well as surface detailing, local environmental regulations governing the removal and disposal of materials, and the type of protective coating specified. “Thorough surface preparation is necessary for the adhesion of new protective coatings,” Waite said. “All loose, flaking, and deteriorated paint must be removed from the iron, as well as dirt and mud, water-soluble salts, oil, and grease. Old paint that is tightly adhered may be left on the surface of the iron if it is compatible with the proposed coatings.” When it comes to the selection and application of new coatings for cast-iron restoration projects, Waite recommended:

* For more information, read “The Maintenance and Repair of Architectural Cast Iron” by John G. Waite, AIA, technical preservation services, National Park Service (NPS), 1991. |

All cast-iron components replicated at the foundry in Belgium were galvanized in molten zinc prior to receiving a shop-applied coating of polyamide epoxy with fast-curing and rapid handling properties, well suited for steel fabrication.

[14]

[14]On arrival at the jobsite, each cast-iron component was fully coated inside, outside, and on its edges with two coats of a patented water-based epoxy to provide durability and corrosion resistance. A finish coat of aliphatic acrylic polyurethane provided resistance to abrasion and weathering.

Coating applicators from Traditional Waterproofing & Restoration worked from pipe scaffolding under a containment system to prevent debris from drifting onto adjacent properties and vehicles. Coatings were applied in accordance with the manufacturer’s specifications using brushes, rollers, and airless sprayers.

The façade’s sheet metal cornice was shop-primed with a water-based, rust-inhibitive acrylic coating, followed by a finish coat of a water-based, high-dispersion pure acrylic polymer. The polymer was also used on wood window frames to match the overall color of the façade.

Since new sheet metal tends to flex, it is inadvisable to apply thick, stress-inducing coatings due to the risk of delamination. Therefore, thin acrylic coatings were specified to provide tenacious adhesion, long-term protection, and color retention on sheet metal.

Water-based coatings are specified for use when low-odor and low-VOC performances are being considered, Gonnella noted. Of the 50 to 60 New York cast-iron restoration projects Gonnella has worked on, solvent-based coating systems were usually specified.

77 Mercer Street

[15]

[15]A three-coat system of solvent-based, zinc-rich primer, followed by an acrylic polyurethane intermediate coat and a fluoropolymer topcoat, was specified for 77 Mercer Street, a circa-1876 cast-iron building located in the SoHo Historic District. This New York City landmark functioned as a store and loft building before being converted into a condominium.

The scope of the 77 Mercer Street project involved rehabilitation of the cast-iron structure, design of a decorative metal cornice, sidewalk restoration, and waterproofing to correct moisture infiltration issues. Design and engineering services were provided by New York-based Form Space Image[16] (FSI) Architecture PC.

The project’s zinc-rich urethane primer and aliphatic acrylic polyurethane intermediate coat provided the building’s exterior cast iron with resistance to abrasion, corrosive fumes, and extreme weathering. The fluoropolymer finish coating in both solid and metallic colors was specified for its ultraviolet (UV) light stability, long-term durability, and aesthetics. In the author’s experience, the life expectancy of fluoropolymer coatings is two to three times greater than traditional polyurethane coatings.

Another solvent-based coating system favored by New York specifiers for cast-iron exteriors uses two coats of a modified polyamidoamine epoxy, a suitable foundation for an aliphatic acrylic polyurethane topcoat for resisting abrasion, wet conditions, corrosive fumes, and exterior weathering, Gonnella said.

[17]

[17]“A significant amount of time, effort, and hard work goes into restoring cast-iron architecture that is very old and often in a state of terrible disrepair,” he explained. “This is why landmark projects like those in New York’s cast-iron historic districts require long-lasting coating technology that provides protective and aesthetic performance.”

Both the 54 Bond Street and 77 Mercer Street restoration projects received warranties from the coating manufacturer based on variables such as surface preparation, method of application, and the performance characteristics of the coatings specified.

Conclusion

The 19th century left New York City with a remarkable legacy of cast-iron architecture. This style has experienced a renaissance in recent decades with the restoration of several landmark buildings in the city’s historic districts. Restoring these 150- to 160-year-old landmark buildings is a major endeavor. In addition to rusting and damage of the façade’s decorative metal, a close inspection often reveals hidden conditions such as broken connections anchoring cast-iron assemblies to the building and points of leakage. The scope of work often requires the removal, replication, and reattachment of thousands of cast-iron and sheet metal features treated with high-performance primers and coatings in order to maximize long-lasting protection and aesthetics.

Jennifer Gleisberg, CDT, LEED GA, is the inside sales manager, eastern region, for Tnemec Company, where she provides sales support to Tnemec’s independent sales representatives. She is a National Association of Corrosion Engineers (NACE) coatings inspector (Level I Certified) and a member of the Society of Protective Coatings (SSPC) and the U.S. Green Building Council (USGBC). With more than 10 years of experience in the coatings industry, Gleisberg brings a customer service perspective to architectural projects requiring coating solutions. She can be reached at gleisberg@tnemec.com.

- [Image]: https://www.constructionspecifier.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/12/5-54-Bond-Street-After.jpg

- architecture: https://architecturaltrust.org/easements/about-the-trust/trust-protected-communities/historic-districts-in-new-york/soho-cast-iron-historic-district/

- masonry: https://architecturaltrust.org/easements/about-the-trust/trust-protected-communities/historic-districts-in-new-york/soho-cast-iron-historic-district/

- façade: https://architecturaltrust.org/easements/about-the-trust/trust-protected-communities/historic-districts-in-new-york/soho-cast-iron-historic-district/

- [Image]: https://www.constructionspecifier.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/12/1-54-Bond-Street-Before.jpg

- cast-iron: https://www.nps.gov/tps/how-to-preserve/briefs/27-cast-iron.htm

- [Image]: https://www.constructionspecifier.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/12/4-54-Bond-Street-During.jpg

- original design: https://www.nps.gov/tps/how-to-preserve/briefs/27-cast-iron.htm

- [Image]: https://www.constructionspecifier.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/12/2-54-Bond-Street-Detail-During.jpg

- Historic Places: http://nyrej.com/54-bond-wins-preservation-award

- [Image]: https://www.constructionspecifier.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/12/3-54-Bond-Street-During.jpg

- [Image]: https://www.constructionspecifier.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/12/11-54-Bond-Street-After.jpg

- [Image]: https://www.constructionspecifier.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/12/10-54-Bond-Street-After.jpg

- [Image]: https://www.constructionspecifier.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/12/77-Mercer-St04.jpg

- [Image]: https://www.constructionspecifier.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/12/77-Mercer-St01.jpg

- Form Space Image: http://www.fsi-architecture.com/facaderestorations/

- [Image]: https://www.constructionspecifier.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/12/77-Mercer-St03.jpg

Source URL: https://www.constructionspecifier.com/preserving-architectural-treasures-in-new-yorks-historic-districts/