Protecting a structure against air intrusion

by arslan_ahmed | November 29, 2022 9:00 am

[1]

[1]By John Chamberlin

Air barriers create airtightness and help protect against energy loss, water infiltration, and other hazards impacting the durability and resiliency of a building and the comfort and health of its occupants. Climate conditions, temperature, location, and intended use of a building all are factors to consider for the specification and selection of air barriers.

As airtightness in buildings is better understood and more closely monitored, newer technologies simplifying installation and quality control (QC) of construction also improve the likelihood of protecting a structure against air intrusion. This article examines the importance of air barriers in modern construction, the evolution of such technologies, the types of technologies available, installation tips and challenges, as well as several case studies.

Building Science Digest summarizes the challenges of airflow this way: “Airflow carries moisture that impacts a material’s long-term performance (serviceability) and structural integrity (durability), behavior in fire (spread of smoke), indoor air quality (distribution of pollutants and location of microbial reservoirs), and thermal energy.”1

Unchecked air movement can impact energy loss and efficiency, translating to wasted money on climate control. Further, airtightness has been implicated as a rationale for reducing the size of controls. This concept has not gained as much momentum as air’s role as a vehicle of water. Initially, vapor or moisture control generates greater interest, but air intrusion is often the gateway to vapor and water.

Air leakage also carries moisture which can impact a structure’s durability and resiliency. Air conveys vapor—which condenses into humidity and water once inside a building envelope. Humidity and water cause corrosion, damage to building materials, and mold and mildew growth; all these factors influence occupant health, an issue which has become top of mind for building owners and occupants as the pandemic reinforced the importance of air barriers in infection control.

In April 2021, The American Society of Heating, Refrigerating and Air-conditioning Engineers (ASHRAE) released a position document to offer guidance on mitigating disease transmission and readying buildings for post-pandemic operations. In it, ASHRAE offers insights on changes to building operations, including mechanical systems and humidity levels which can reduce airborne exposures and microorganism levels.

A subsequent article in The Construction Specifier on “The role of air barriers in disease transmission” expanded on these issues: “Air movement is typically considered to move significantly larger volumes of water vapor through or within the enclosure than vapor diffusion and is a concern from an infection control perspective, enclosure performance parameter, and operating costs associated with maintaining the elevated humidity.”2

Such health considerations demonstrate why air barriers are important, not just at the onset of a building’s construction, but throughout its lifecycle.

[2]

[2]Evolution of air barrier technologies

Air barriers are a newer building component, emerging over the last 40 to 50 years—with the greatest results occurring in the last 20 years, as manufacturers, contractors, and others have become better and smarter.

Building wrap

Building wrap over sheathing has been used since the 1960s. When professionally installed, it is among the most economical air barriers. Installers must cut and fold the material properly around rough openings, and appropriately lap and tape everywhere to form a complete barrier.

Building wrap technology has advanced over the years, and specifiers now have several fabrics and accessories to match to their application. Among the considerations is the knowledge that wraps can rip or tear. Traditionally, wraps use fasteners to attach to buildings, creating opportunities for it to loosen against the building, especially in high-rises. Installers punch holes through the wrap which can provide air and water access to structural walls or allow weather elements to pull against the fasteners, permitting the wrap to tear away in strong storms and, at times, in mild breezes.

Role of an air barrier

Air barriers have a singular purpose: keep outdoor air out, and indoor air in. Simple to say, but not as simple to do. Air barrier systems should be:

- Impermeable to air flow.

- Continuous over the entire building enclosure or continuous over the enclosure of any given unit.

- Able to withstand the forces which may act on them during

or after construction. - Durable over the expected lifetime of the building.1

Note

1 Consult BSD 104: Understanding Air Barriers by Joseph Lstiburek, Building Science Corporation, Oct. 24, 2006. https://www.buildingscience.com/ documents/digests/bsd-104-understanding-air-barriers.

[3]

[3]Self-adhered membranes

Self-adhered (peel-and-stick) membranes emerged in the last 20 to 30 years and have impressive flexibility and strong adhesion, often making them excellent around rough openings and other wall penetrations. However, if seams are not fully adhered or properly lapped, low permeable membranes can trap and hold water if moisture penetrates to the sheathing through the seams, accelerating the very problems of moisture-related decay they were designed to prevent.

Liquid- or fluid-applied membranes

Liquid-applied or fluid-applied membranes were first introduced around 2000s and create a continuous coating, tightly sealing the building against water and air intrusion without additional fasteners. Though more expensive than building wrap, these membranes are considered competitively priced due to their ease of installation. Liquid-applied barriers go on easily, and almost anyone can apply this type of product with a roller or sprayer. However, this can be a disadvantage.

With liquid-applied air barriers, it is important to have the right thickness (mil) on all areas of the building. This can be hard for a novice installer to achieve since there are coating thickness variations. Whether spray- or roller-applied, the wet thickness of applied material should be routinely checked and verified by the applicator to confirm proper coverage.3 If the milage is too thin, the barrier will not perform in the way it is designed, and reapplying over the thin spots adds extra labor and product consumption to the project. Contrastingly, if the coating is applied too thick, it can hinder drying time, affect performance, and increase labor and product costs.

Water-resistive barrier-air barrier (WRB-AB)

Integrated sheathing reduces the potential for installer error associated with field-applied water-resistive barrier-air barrier (WRB-AB) systems and offers a faster, easier installation process, and provides the protection of a continuous WRB-AB.

Products that integrate an exterior sheathing and water-resistive technologies to form a hydrophobic, monolithic surface, block bulk water but allow vapor to pass through, eliminating the need for an additional external WRB-AB. With the WRB integrated with the sheathing, contractors do not need to walk the building again with a wrap, and owners can feel confident in the coating’s uniform thickness and cure.

By removing an entire installation step, integrated systems save on installation time compared to traditional fluid-applied or building wrap methods. Crews can move on to the next job faster, and safety risks are reduced with fewer trades and less time spent on the job.

Understanding the codes

As air barrier products and systems evolve, so do building codes and testing standards. Just as air barrier systems are relatively new, building codes and testing requirements are new as well.

The most updated and frequently referenced building code appears in section C402.5 of the International Energy Conservation Code (IECC). The 2021 version of the code contains details for air barrier materials, building envelope performance, and testing—all of which vary based on building components, location, and building type.4

This, and all building codes are model codes only, and it is up to state and local governments to adopt them fully or in part. For example, projects in Washington, the United States General Services Administration (GSA), and United States Army Corps of Engineers (USACE) all require whole building airtightness testing, and each has its own standard of airtightness. Some different standards of include:

- 2015 IECC; 0.2 L/s•m2 (0.42 cfm/sf) at 75 Pa (1.57 psf)

- USACE; 0.118 L/s•m2 (0.2500 cfm/sf) of flow at 75 Pa (1.57 psf)

- Passive House Institute (PHI); 0.00085 to 0.0043 m3/min (0.03 to 0.15 cfm)

- Seattle Energy Code; 1.5 L/s/m2 (3.17 cfm/sf) at 75 Pa (1.57 psf)

The Air Barrier Association of America (ABAA) explains: “Airtightness testing is a process in which the building envelope is tested to quantify airtightness. The test measures air leakage rates through a building envelop under controlled pressurization and depressurization.”5 ABAA also notes testing is not mandatory or prescribed in building codes, but a performance-based option designers may require.

ABAA provides standard testing methods for building enclosure airtightness compliance (ABAA T0001-2016), for pull-off strength of adhered WRB-AB using an adhesion tester (ABAA T0002-2019), and for determining gap bridging ability of WRB-AB barrier materials (ABAA T0004-2021).6

ASTM indicates how to test based on building location and climate zone, and it can be performed on the materials or individual components alone, the assembly, or the whole building. The first and most basic testing is the material alone as indicated in ASTM E2178, Standard Test Method for Air Permeance of Building Materials, which measures the air permeance of flexible sheet or rigid panel-type materials and determines their suitability as a component of an air retarder system. Assembly testing, described in ASTM E2357, Standard Test Method for Determining Air Leakage Rate of Air Barrier Assemblies, is for wind pressure loading.

Materials can behave differently when tested on their own compared to testing within an assembly. For instance, most air barrier materials test well independently; however, it is the testing of the assembly and/or the whole building where most issues often occur.

“Combining the testing of the individual materials and accessories, as well as testing for the wall assembly is most effective. Testing on the material alone can provide misleading results,” writes Vanessa Salvia, a freelance writer who specializes in the construction industry. 7

Whole building tests, outlined in ASTM E779, Standard Test Method for Determining Air Leakage Rate by Fan Pressurization, evaluate the assembly, its installation, and measure the building’s airtightness. The most common is the whole building blower door test, which is used to verify compliance with the airtightness goal. Additional details on orifice blower door testing are found in ASTM E1827, Standard Test Methods for Determining Airtightness of Buildings Using an Orifice Blower Door.8

How the whole-building blower test works

First, every opening in the building is sealed off. A membrane is placed at the blower door with a big fan at the bottom. The fan is turned on and air is sucked out of the house, creating a vacuum, during which gauges inside and outside the building measure air pressure. Changes in air pressure, air changes per hour (ACH), indicate the tightness of the building. The lower the number of ACH, the tighter the structure.

Quality control (QC)

The difficulty with air barriers is combining different building products to create a continuous air barrier around a building, making continuity the biggest challenge.

With building wrap, every different course of the wrap must be taped against the previous course in an airtight way. Additional steps and time invested in finding issues can increase costs. Using building wrap as an air barrier is increasingly becoming uneconomical due to the shortcomings associated with mechanical fastening and penetration; some now view building wrap as more of a WRB rather than an air barrier.

Self-adhered membranes take away the risks of penetrations because installers seal each additional course to itself. With self-adhered products, installation steps are priming, laying the material accurately, coming back with a hard roller to adhere membranes, and sealing it with termination mastic to maintain air continuity. However, each of these steps requires near perfect jobsite conditions since weather elements such as wind, dust, water, or frost can impede installation and quality.

When a self-adhered air barrier is not fully airtight, workers must go back and locate potential air leakage by peeling back layers or going inside and patching leaks. Self-adhered products, if not installed perfectly, can be more difficult to problem solve and more costly due to increased labor usage.

Fluid-applied membranes are simple to install but difficult to manage, in terms of finding a straight line, maintaining appropriate mil thickness, and allowing for differing curing environments. For example, wall application can be challenging, especially where requirements call for as much as 40 mils and as little as 15 to 20 mils. If sheathing is out of plane, or concrete blocks or poured concrete have pits and high spots, a leak is bound to occur. Application needs to be consistent at thick enough milage for airtightness and water resistance, but not thick enough to break budget with excessive material and labor costs.

Overapplying fluid-applied membranes can cause the product to run or droop. Installers must understand how products go on the wall, curing time, and proper sequencing. Quality control can involve looking for pits and voids, including pinholes and areas without continuity, since fluid-applied membranes shrink, move, and change form with building once cured.

Dry time and weather conditions are also key factors as both membrane barriers often need extended, dry, temperate conditions to ensure proper application and performance. As a result, newer liquid barriers have leveraged special chemistry, allowing consistent mils, quicker cure times, and the ability to be back rolled or not, depending on substrates. Their use in a school retrofit project illustrates some of the advantages.

Integrated WRB-AB sheathings innately contains most of the two barriers at the onset since they are adhered together. When installing the sheathing, most of the barriers are also installed. The only additional step is sealing penetrations, joints, seams, gaps, and rough openings to structural members by going over fastener heads with liquid flashing or tape. As a result, the only opportunity for an air leak is if there is a hole.

The integrated product itself has uniform thickness and can be visually inspected with relative ease, simplifying the guesswork related to many issues experienced with other technologies. Other benefits of an integrated WRB-AB system include not being weather dependent, requiring little to no cure time, and coming from a single source, which leads to increased support and supplier accountability. Integrated WRB-AB sheathing systems are easier to install and manage quality control, increasing the likelihood of successful airtightness and reducing rework and callbacks.

Brentwood Elementary School in Austin, Texas

Originally constructed in the 1950s, Brentwood Elementary School in Austin, Texas, has undergone multiple renovations over the years. Recently, school officials decided to undertake a full-scale modern renovation of the school’s enclosed 8362 m2 (90,000 sf) area to bring

its buildings up to where they wanted it to be.

In the initial mockup of materials, challenges arose with the chosen liquid barrier because it would not adhere properly to the already installed water-resistive barrier-air barrier (WRB-AB) sheathing system. This is an example of how various products and systems can create compatibility and adhesion challenges. Fortunately, an alternate single-component, monolithic, elastomeric, silane-terminated polymers (STP)-based fluid-applied WRB-AB was found. The only concern? It was new to the team working on the project.

The product manufacturer sent a representative to the jobsite to share the product, collaborate with the team, review discrete information, educate the crew on installation techniques, and raise the comfort level. The product was then assessed and added to the mockup ahead of the full review by the project’s drywall consultant. It was chosen for the project to mitigate the risk of unwanted air movement, protect against water intrusion, and help modernize the 70-year-old structure.1

Several key elements led to the chosen WRB-AB being selected as the product of choice for this renovation. Choosing a WRB means only one trip around the building for installation (opposed to multiple trips for other products) which translates directly to time and labor saved. Given the tight building schedule, all renovation needed to happen while the school was closed, the product manufacturer was able to meet the product delivery deadline, even allowing for a buffer zone to compensate for potential weather delays. Lastly, the non-combustible nature of the product meant once it was installed and covered with brick cladding, the entire wall was non-combustible.

Note

1 Read this case study on Brentwood Elementary School, “Acing a School Renovation: Finding Compatible Materials Against Water Intrusion.” Visit https://buildgp.com/denselement/case-study/acing-a-school-renovation-finding-compatible-materials-against-water-intrusion.

[4]

[4]Scheduling and financial implications

Beyond QC measures, air barriers can either increase or decrease construction schedules and project costs, depending on the selected technology. Costs are driven by the price of product and the price of installation.

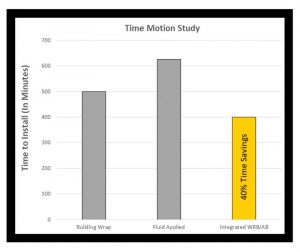

Labor costs are the primary differentiator since trips around the building require time and costs. Eliminating a trip around the building with an integrated system can provide a higher level of efficiency over products which must be applied on top of a sheathing. Reduced trips around the building translate to fewer components, less time for QC, and fewer areas to check and correct (Figure 1, page 47).10

Cure times and weather also factor heavily into schedules and costs. Cure times do not correlate to labor costs directly; however, it does impact costs and schedules if workers are on the clock but not engaging physically. Similarly, weather can impact installation times since peel-and-stick and other acrylic products cannot adhere to wet surfaces.

Passing the test

Once selected and installed, it is time to assess for air leaks. Identifying and testing for leaks can be a huge challenge. The most common sources of air leaks are areas where one section joins another section, such as fenestration systems, floor lines, parapets, and differing substrates (e.g. framed construction hitting block construction). When leaks occur, tests are used to find the source.

Testing options range from thermographic imaging, to finding cool spots where air might be moving, to smoke tests where smoke is released and creates a path to follow. Infrared tests provide a baseline awareness for areas of concern but can be limited since outside ambience can impact results. Smoke tests can be helpful but expensive for more finite testing, such as smaller air leaks where a fastener was not treated or a window seal with air permeance.

Blower door tests are often performed right after fenestration installation to check for an airtight seal between windows and the rest of building prior to painting and other aesthetic finishes. Blower door tests are also used as a primary mechanism for testing whole building airtightness.

If a project fails a whole building airtightness test, determining why it failed and how to pass becomes a top priority. Solutions vary based on the stage of construction at testing and where the leak occurs. With some such as, self-adhered membranes, the answer can be as simple as applying sprayfoam on the interior or from another part of the building.

Just as solutions to a failed whole building airtightness test vary, so do the consequences. Based on the project’s locale, consequences change since states are adopting different codes. If the project is in Washington, the certificate of occupancy will be delayed or denied. In other areas, building performance may be downgraded, such as a lower Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design (LEED) standard.

Eagles Landing Apartments, Burlington, Vermont

It is no secret a building is more likely to have an air or water leak where a hole is cut through, and the more windows or rough openings, the more chances of a leak happening, which leads to lack of airtightness. Every seam or penetration creates potential for moisture or air intrusion.

The Eagles Landing apartments in Burlington, Vermont, was a 5575 m2 (60,000 sf) student housing project, designed with 105 apartments; each with an average of five windows, spread across five floors, and 484 m2 (5200 sf) of ground-floor commercial space. Adding to the challenge was the continuous insulation (ci) energy requirement, which required 63.5 mm (2.5 in.) of exterior insulation applied over the water-resistive barrier-air barrier (WRB-AB) system.

To meet this requirement, the project’s architects had to frame out the rough opening with wood. Traditionally, self-adhered membranes are used to wrap the extended opening. However, doing this across 600 windows could increase the length of the project and open the door

to many frustrations.

For this project, an innovative, integrated WRB-AB sheathing solution with liquid-applied flashing presented a better solution to a traditional self-adhered membrane because it bonded and conformed to window openings and was easier to visually inspect.

In addition, the vapor-permeable liquid flashing allowed the windows wood frames to dry, and this helped prevent rotting and contributed to the project saving at least two months. After installation, the selected system was tested with a blower door test to verify the building’s airtightness performance. The result was 0.001 m3/min (0.035 cfm/50 sf), which exceeds the average standard airtightness compliance testing and is incredibly airtight.

Conclusion

Choosing an air barrier is a balancing act between building performance, material cost, and installation expertise. One of the best ways to balance the various considerations is to install an air barrier system which achieves airtightness standards for the project and meets local requirement of different states, and has simpler QC methods.

Most air barriers work well when installed correctly, but specifiers, contractors, and owners need to weigh a variety of factors such as budget, climate, and how long the building is expected to last to choose the right one for a project. Among the other factors to consider are the project’s location, governing building codes, and testing requirements.

Evaluating a building’s airtightness is important for many reasons: to increase indoor occupancy comfort, to reduce outdoor pollutants, and to prevent moisture entering a building which can lead to mold and mildew. Airtightness also helps with noise transmission, has a big energy efficiency component, and contributes to QC.

Quality assurance (QA) programs from a variety of agencies and associations such as ABAA can help determine the best air barrier technologies, testing practices, and problem-solving methods. Each has different opinions about testing frequency and at what points those checks should occur but can be

a valuable resource to optimize the airtightness

of projects.

Notes

1 Read Joseph Lstiburek, “BSD-104: Understanding Air Barriers,” Building Science, October 24, 2006. Visit https://www.buildingscience.com/documents/digests/bsd-104-understanding-air-barriers.

2 Refer to Flock, Sarah K., CDT, AIA, and Dunlap, Andrew, AIA, CDT, LEED AP, NCARB. “Role of Air barriers in mitigating disease transition.” The Construction Specifier, January 18, 2021. Visit https://www.constructionspecifier.com/role-of-air-barriers-in-mitigating-disease-transmission.

3 Visit Schaack, Karl, RRC, PE. “Potential Issues Encountered During Installation of Air and Weather-Resistive Barriers,” International Institute of Building Enclosure Consultants, May 1, 2020. Visit https://iibec.org/issues-encountered-

with-barriers.

4 Read International Energy Conservation Code (IECC), Chapter 4, C402.5 https://codes.iccsafe.org/content/IECC2021P1/chapter-4-ce-commercial-energy-efficiency#IECC2021P1_CE_Ch04_SecC402.5.

5 See The Air Barrier Association of America (ABAA) codes, https://www.airbarrier.org/technical-information/whole-building-air-tightness-testing-2.

6 See The Air Barrier Association of America (ABAA) standards on testing, https://www.airbarrier.org/technical-information/abaa-standards/

#1645814857358-636b8c58-a424.

7 Read the article by Salvia, Vanessa. “Air Barriers,” Waterproof Magazine, Summer 2018. Visit https://www.airbarrier.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/WP_2018-06_Air-Barriers.pdf.

8 Refer to the American Society for Testing and Materials (ASTM) codes on Air Barriers. https://www.astm.org/e1827-11r17.html.

10 See data on air barrier installation. “Time-Motion Study of the DensElementTM Barrier System,” Home Innovation Research Labs, August 17 – 20, 2015. Visit https://studylib.net/doc/18794183/denselement%E2%84%A2-barrier-system—summary-of-time-motion-study.

Author

Author

John Chamberlin is the senior product manager at Georgia-Pacific and is responsible for the DensElement® Barrier System and the DensDefy line of products. He has worked in the building products industry his entire career, with most of his work focusing on new product development for disruptive technologies in the building envelope space. Chamberlin is actively involved in the building industry, serving as a member of multiple committees and director for the board of the Air Barrier Association of America (ABAA) and is a frequent attendee of his local Building Enclosure Council (BEC). Chamberlin graduated from the University of Tennessee with a bachelor of science degree in marketing. He later received his MBA from Emory University.

- [Image]: https://www.constructionspecifier.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/3-56am-Production-78-of-90.jpg

- [Image]: https://www.constructionspecifier.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/3-56am-Production-66-of-90.jpg

- [Image]: https://www.constructionspecifier.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/3-56am-Production-53-of-90.jpg

- [Image]: https://www.constructionspecifier.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/Time-Motion-Study.jpg

Source URL: https://www.constructionspecifier.com/protecting-a-structure-against-air-intrusion/