Protecting our historic glazing

by Katie Daniel | May 30, 2016 2:10 pm

by Kurtis Suellentrop, EIT

According to the National Park Service (NPS), “when historic windows exist, they should be repaired when possible. When they are too deteriorated to repair, selection of the replacement windows must be guided by Standard 6 [of the Secretary of the Interior’s Standards for Rehabilitation].”

Repairing historic windows is an admirable goal, but the reality of today’s tough requirements for windows often makes their replacement a more logical and economic choice. Whether the project calls for repair or replacement, there are new technologies and products that can help designers replicate historically accurate sightlines and aesthetics. This can be particularly difficult to achieve on existing structures while maintaining historic accuracy, but several manufacturers now offer good historic replication solutions.

Today’s environmental and manufactured threats to buildings range from seismic forces, high winds, and temperature extremes to security breaches, air infiltration, and acoustic issues.

Originally, windows were designed for weather resistance, ventilation, and daylighting, but current building and construction environments require windows to do much more. Historic structures were not designed to meet current International Building Codes (IBC) and wind load requirements.

Therefore, it can be exceptionally difficult to integrate protection from these hazards in new construction, but can be even more difficult to achieve on existing structures while maintaining historically accurate sightlines and aesthetics. There are many factors contributing to a building’s significance and historical value, but according to NPS, they are generally at least a half-century old and contribute to:

…the historic significance of a district …by location, design, setting, materials, workmanship, feeling and association adds to the district’s sense of time and place and historical development.

This article suggests several aspects to consider when designing a historic window repair or replacement project. Many of these concepts can also be used in new construction when the building is designed to replicate the feel of a historic building.

Understanding the terms

Considering the costs and benefits of the repair/replace decision requires a firm understanding of terms and definitions. It is also beneficial to understand historic construction techniques and methodology.

Grids

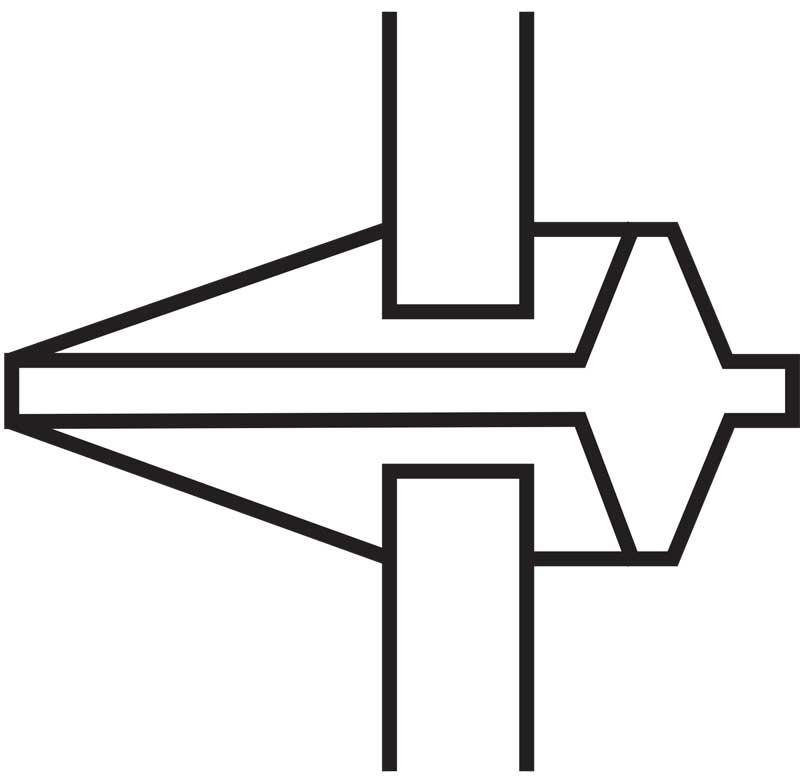

Depending on the region of the country, this component can also be called mutin, muntin, or bar. They were originally used to receive the monolithic glass in wood and steel windows (Figure 1). The styles are also replicated in more modern aluminum assemblies, with simulated divided lites (Figure 2).

Shadow line

The shadow line refers to the depth of the trim, window, or glass from the referenced vertical or horizontal surface. For example, in Figure 3, there is a shadow cast at the horizontal meeting rail and the head trim in this hung wood window from a 1950s Atlanta courthouse.

Finish

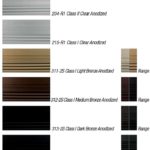

Originally, the limitations of few pigments, lead, and linseed oil paints were used for wood or metal windows. Various light stone colors and dark-purple, brown, chocolate, oak, drab, and green were common finishes used. Over the decades, improper maintenance through the layering of heavy paints can damage and alter the appearance, as well as hinder operation. However, it is possible to replicate these finishes using modern, more durable products. Current metal finishes include epoxy, liquid-applied polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) resin, polyester triglycidylisocyanurate (TGIC) resin powder coat, and anodized (Figure 4, page 26). Modern powder coat finishes are also able to achieve a wood grain pattern appearance on an aluminum substrate. Restored materials must typically be mechanically or chemically stripped to the raw surface, and then repaired, primed, and painted.

Mullions

The vertical separations between windows are typically referred to as mullions. On most original wood double-hung windows, they were very wide to accommodate multiple counter-balance weights in the window cavity. Many historic elements in traditional cast iron or wood mullions can be preserved and reused or replaced by more modern materials. They are critical to the overall aesthetic of the building envelope.

Operation

Typically, historic windows do not have to match the original ventilation operation, or even open at all based on the mechanical or HVAC requirements. However, the sash (i.e. operable portion of the frame) and perimeter sightline should replicate the existing system. Over the past few decades, fixed windows became more common, but recent feedback and design codes highlight the importance of natural ventilations for building performance and occupant comfort.

Glazing

To achieve current energy codes, the glazing system may require several layers of glass, spacers, low-emissivity (low-e) coatings, tints, or even dynamic lighting control systems. The protection requirements may require a film, laminate, or polycarbonate. All these materials may decrease the visibility and increase the color shift. This must be taken into consideration when evaluating the aesthetic impact and balancing it against the project budget. While it can be difficult to specify glass clarity without a sample, it can be defined using a few methods.

Visible light transmission

The percentage of visible light at normal incidence (90 degrees to surface) transmitted by the glass is known as visible light transmission (VLT). This is measured as a percentage, with the maximum being 100 percent. For example, most car windshields must be minimum 70 VLT.

Color rendering index

The change in color of an object as a result of the light being transmitted by the glass is known as the color rendering index (CRI). This is measured as a value from 0 (opaque) to 100 (daylight). For example, most museum quality glass must exceed 95.

Color comparison chart

This color comparison chart is a method of plotting the reflected or transmitted color from yellow, red, blue, and green with clear glass at the center. Three of the common glass make-ups are:

- clear monolithic;

- clear double silver low-e laminated; and

- ultra-clear triple silver non-laminated.

Installation device

One of the most difficult, but critical aspects of any retrofit installation, is the integration of the new windows into the existing substrate. A complete or partial demolition is necessary to determine the condition of the wall. Furthermore, testing should be done by a fastener testing company or lab to determine what loads can be accommodated for future engineering.

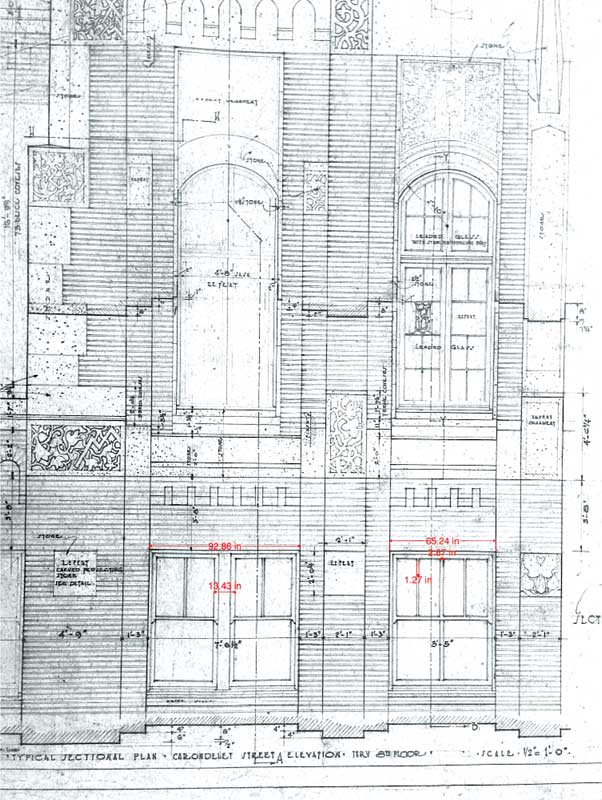

Typically, the original architectural drawings or blueprints are not sufficiently detailed to assist in the new system installation development. Historic buildings have also been renovated and revised and may no longer accurately reflect the original design intent. An example of this can be found in the 600 Carondelet Building in New Orleans, which was originally designed as the Maison Blanche Building by Weiss, Dreyfous, and Seiferth Architects in the mid-1920s (Figure 5). Unfortunately, the original wood vertically hung windows were replaced by fixed windows that did not reflect the original character of the building (Figure 6). However, the architectural firm, Eskew-Dumez & Ripple, was able to track down several photographs and drawings to help determine what the original windows looked like, helping the team design and create new windows replicating the originals.

Initial investigations discovered the original wood frames were still intact, and even the counter-balance weights were still in the pockets (Figure 7). Unfortunately, this demolition also revealed the existing structure was not enough to handle the fastener loads required for the new hurricane-resistant windows (Figure 8). Additional metal framing was required in order to reinforce the jambs without affecting the overall window sightline.

This advanced research, partnership, design, and testing allowed for a final installation that was able to restore the building to its original glory and design while meeting the current stringent, high-performance window and hurricane codes.

Materials used in historic installation can be hazardous when disturbed, therefore, testing should also be done on the paint, insulation, glazing putty, and frame caulking. This can be critical on larger projects as it may be more beneficial to create custom trim shapes to encapsulate the ‘hot’ materials.

801 S. Skinker is a multi-family condominium project overlooking Forest Park in St. Louis. When the ownership group started looking at window replacement of the original 1950’s single pane, non-thermal windows, the anticipated cost of asbestos abatement was prohibitively high. The installation team looked at several options alongside the manufacturer and decided to develop a custom perimeter trim. This trim had an extended leg that allowed the original glass to be removed and the frame to remain in place, encapsulating it and leaving the perimeter caulking undisturbed. This resulted in a sleek, quick, and less-intrusive installation for the residence, along with a savings of $250,000 (Figure 9).

Scheduling and sequencing

This environmental testing and design must be done sufficiently in advance of the project schedule to allow for sufficient time for development.

Some of these processes can happen concurrently so they are not cumulative, but it does highlight the importance of the early planning stages to meet the project timeline.

The glass and mutin are obviously the most visible portion of the windows, especially from an occupant’s perspective. Due to manufacturing limitations, historic glass originally was much smaller and thinner, with inherent lines, waviness, and even bubbles. This can still be reproduced using modern technology from specialty companies on a limited basis.

For most projects, standard monolithic or insulated glass is sufficient and more cost-effective. The thicker glass required can cause a visible color shift, especially compared to the original single strength glass. Most glass manufacturers offer a clearer, low-iron glass that reduces the amount of tint, which is especially useful on heavier, thicker glass.

The glass can be designed and submitted based on VLT. However, samples should always be submitted, and even full size mockups provided, before production if possible.

Similarly, the mutin can play a critical role in the aesthetic of the windows system. Replicating the original true divided lite (TDL) glazing with modern systems can provide the truest reproduction of the original windows. Historic windows would typically have only 6 to 9.5 mm (1⁄4 to 3⁄8 in.) of glass bite—the overlap of the glass into the frame. As shown back in Figure 1, the resulting sightline would be less than 25 mm (1 in). However, modern Glass Association of North America (GANA) glass bite requirements of 12.5 to 25 mm (1⁄2 to 1 in.) make this narrow dimension nearly impossible in a true divided lite system.

To minimize sightline and maximize performance, many manufactures also offer a simulated divided lite (SDL) system. This consists of an exterior profile attached using mechanical or adhesive on the exterior of the glass. The interior of the glass also has a flat or contoured profile for added depth and visual weight. Finally, on insulated glass units (IGUs), an internal spacer bar is added to reduce the vision between the exterior and interior profiles.

The SDL method also has the added benefit of reduced labor and improved thermal, wind resistance, acoustic, and water infiltration performance. Glass manufacturers have a minimum square footage for each lite of glass—meaning there can be a significant cost savings from the reduced net effective glass area.

Conclusion

There are several interconnected aspects and concerns to address in a historic renovation or replication project. However, when an early partnership is formed between the specifier, architect, installer, and experienced window manufacturer, the combined effort and knowledge can provide a successful installation that adds to the building’s historic character at a competitive cost.

Kurtis J. Suellentrop, EIT, is a technical sales and business development manager with Winco Window Company, which is headquartered in St. Louis. He is a graduate from the University of Missouri-Rolla with a degree in mechanical engineering and an emphasis in design and thermodynamics. Suellentrop oversees Winco’s R&D program, including multi-threat systems encompassing psychiatric, dynamic, acoustic, thermal, tornado, and hurricane windows. He can be reached via e-mail at kurtissuellentrop@wincowindow.com[1].

- kurtissuellentrop@wincowindow.com: mailto:kurtissuellentrop@wincowindow.com

Source URL: https://www.constructionspecifier.com/protecting-our-historic-glazing/