Signal-to-noise ratio

Initially, acousticians were primarily interested in evaluating the conditions needed to clearly hear sounds. They determined the critical factor was the level of the desired sound—called the ‘signal’—relative to the background sound present in the listener’s location. In most cases, the background sound used during testing was broadband and did not contain information (i.e. noticeable patterns, such as running speech, nature sounds, traffic noise). However, it was termed ‘noise’ because it could potentially interfere with the intelligibility of the desired sound. The ratio of the desired sound to background sound was termed the signal-to-noise ratio.

In the above case, the ‘signal’ is the sound one wants to hear because it conveys useful information, while the ‘noise’ is an unwanted input challenging one’s ability to clearly hear the desired sound. As acousticians developed an understanding of background sound as a fundamental component of speech privacy, the methodology—and the terminology—remained the same. Hence, the word ‘noise’ continued to be used to describe the background—or, in this case, the masking—sound, despite the fact it was now being viewed in a positive light.

Understandably, the term ‘noise’ can cause confusion when the ‘signal’ is the unwanted sound and the ‘noise’ is actually the desired background sound. Meanwhile, the general public tends to use ‘noise’ as a non-technical descriptive word, typically when relating negative acoustical experiences—ones that are uncomfortable, annoying, disturbing, or even painful.

To highlight the difference in the way in which ‘noise’ is used, consider an individual working in an office, who complains about ‘noise’ to a colleague. There are several sources of sound within the space (exterior traffic, fan, and a radio playing music), but the source bothering the individual is a heated debate taking place in the meeting room adjacent to their workspace. In this scenario, the terms are defined in this way:

- sound – there are four sound sources identified in the workplace.

- signal – the noise capturing the individual’s attention

(i.e. the debate) and, hence, the cause of their complaint. - noise – the individual uses the word ‘noise’ to describe the debate. However, if the term is used in a technical assessment of this environment, the ‘noise’ is actually the combination of all other sound sources (i.e. the traffic, fan, and radio), excluding the signal (i.e. the debate).

Technical use of the word ‘noise’ requires a ‘signal.’ In this scenario, noise accounts for the combination of sounds (i.e. it considers everything that is not the signal), while the signal only considers the source of the sound that is of interest.

The human factor

What turns a ‘sound’ into a ‘noise’ in the common vernacular? Humans demonstrate remarkable tolerance to sound and are only susceptible to its disruptions when they become aware of it—typically when the level of sound is too high, its qualities are unbalanced (e.g. it is too ‘hissy’ or ‘rumbly’), or it presents with temporal instability of its dynamic range (i.e. the change and/or rate of change in sound level over time).

Context

A person’s assessment of sound generally depends on personal preferences and expectations for the occupied environment, as well as the activity in which they are engaged. For instance, consider a conversation at ‘normal level’ in two environments: a library and a busy restaurant. In the former, the nearby occupants engrossed in a task requiring concentration are likely to find the conversation too loud, annoying, and disruptive. In the latter, the level of conversation may not be sufficiently loud to allow for clear communication. Expectations are based on an understanding of the purpose of the space and the task at hand.

Content

One’s description of sound tends to focus on two main properties: level (often referred to as volume) and spectral distribution. A ‘hissy’ or ‘screechy’ sound is one that has a lot of high frequency information (e.g. a young child screaming). A ‘bassy’ or ‘rumbly’ sound is one with a lot of low frequency information (e.g. a lion roaring). A space without a balanced sound spectrum can sound worse than one with a higher sound level, but with a balanced spectrum.

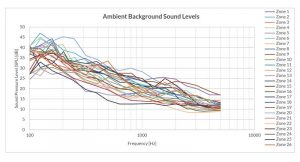

Cover

The human experience is also determined by the space’s background sound level, which is considered to be the collection of all (ambient) sounds within it. Often, a room is too ‘silent’ (i.e. its ambient level is too low) and a source of sound becomes uncomfortable (e.g. a clock ticking, cars driving by, people talking, lights humming). In these cases, the ‘signal’ is disturbing because its level is higher than the background sound. The disruptive impact of these annoying noises can be lessened by reducing the signal-to-noise ratio, which is achieved by raising the background sound level. In some cases, it is possible to raise the background sound level sufficiently to completely cover up these unwanted sounds.