Control layers

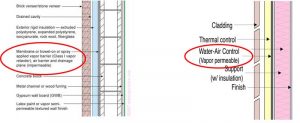

The control layer systems approach acknowledges there are four primary elements that need to be controlled: bulk water, heat, air, and water vapor; and two secondary elements: UV light and sound. Each element may be controlled by a separate layer within the building envelope. For example, an exterior water-resistive layer to resist bulk water, and an interior polyethylene sheet to resist water vapor, or a single layer may be capable of controlling more than one element at a time (Figure 1). Another example would be a metallic faced membrane serving as a barrier to bulk water, air, water vapor, and UV light (Figure 2).

Water-resistive air barriers (WRABs)

A critical and often misunderstood component of the building envelope is the WRAB. This component may be capable of performing multiple control functions required by the building envelope.

WRABs are often constructed using manufactured sheet goods or site-applied liquid membranes, installed to prescribed thicknesses. Each method has its own application advantages and disadvantages, and is often used in combination to leverage these advantages on a project. For instance, a wall assembly may use sheet goods to wrap long straight sections of a window surround, and then apply a liquid to connect more difficult-to-wrap corners or curved sections of the opening (Figure 3).

The role of a WRAB, in order of importance, is as follows:

- Provide a secondary layer of rainwater protection for water that passes through the primary layer of rainwater protection, such as cladding or veneers. To provide this protection, it is important the material itself is not affected by water, is resistant to leaks—due to penetrations (self-sealing) at fasteners—and is able to be detailed with through-wall flashings so it may evacuate accumulated water from the interior of the assembly.

- Provide a barrier to air movement across the envelope, while providing resistance to the design prescribed difference in air pressure. Some air barriers such as glass, metal pan, and rigid boards possess adequate strength to resist such air pressures on their own, but where thin sheets or liquids are incorporated into the air barrier system, they may be incapable of resisting these forces on their own. These thin barriers bring other benefits, such as water resistance and various levels of vapor permeability, to the assembly and rely on their adhesive properties to attach themselves to other materials to gain the strength of the structure or material to which they are adhered.

-

Figure 3 A wall assembly may use sheet goods to wrap long straight sections of a window surround, and then apply a liquid to connect more difficult-to-wrap corners or curved sections of the opening. Provide either resistance or permeability to the water vapor, depending on the design requirements of the barrier. In a cold climate, often WRABs that are protected behind the majority of the walls insulation are designed as Class 1 vapor barriers—those that allow less than 0.1 perm or

5.72 ng/sm2Pa of water to pass per ASTM E96—while those exposed to the colder side of the walls insulation are required to be vapor permeable—those that allow more than 10 perms or 5,721 ng/sm2Pa of water to pass as per ASTM E96—as to not risk condensation occurring within the building envelope.