Rethinking building envelopes for climate-ready buildings

by arslan_ahmed | January 18, 2024 10:00 am

By Paul Johannesson

By Paul Johannesson

As climate change is anticipated, bringing with it an uncertain future, the construction industry needs to seriously consider the preparedness and the proven performance levels of buildings. It also needs to ensure the “large membrane” that separates the exterior environment from the interior environment, also known as the building envelope, is up to the task.

The idea of building resilience has become more topical as everyone comes to terms with the fact that changing climate conditions seem inevitable. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) states, “Taken as a whole, the range of published evidence indicates that the net damage costs

of climate change are likely to be significant and to increase over time.”1

Will there be an increase in both the frequency and intensification of severe weather events? Will there be a need to resist increased water, wind, and temperature extremes in the exterior environment? Will shifting the focus from the approach prescribed within the current codes and standards to a higher performance-based design and commissioning approach be the answer?

The building envelope

The building envelope can be imagined as a “thick membrane” that separates the exterior environment from the interior environment on all sides of a building—similar to a balloon. It has been mistakenly conceived as one or two layers of perfectly sealed materials; and there exists a history of building failures to prove it. It is best described as “part of any building that physically separates

the exterior environment from the interior environment(s) is called the building enclosure or building envelope.”2

It is important to consider this envelope or enclosure is a very complex system of base materials, accessories, pre-manufactured components, riddled with seams and penetrations, and is highly reliant on a systems approach of connecting them to create a weather tight separator of dissimilar environments. These environments are often dissimilar in temperature, relative humidity (RH), wind pressure, and vapor pressure. Each building envelope deals with differences as unique as the climate region or zone it is constructed in. Thankfully, a commonly accepted approach to building envelope and enclosure design has emerged over the years.

[1]

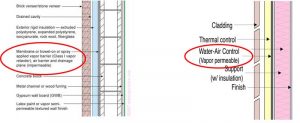

[1]Control layers

The control layer systems approach acknowledges there are four primary elements that need to be controlled: bulk water, heat, air, and water vapor; and two secondary elements: UV light and sound. Each element may be controlled by a separate layer within the building envelope. For example, an exterior water-resistive layer to resist bulk water, and an interior polyethylene sheet to resist water vapor, or a single layer may be capable of controlling more than one element at a time (Figure 1). Another example would be a metallic faced membrane serving as a barrier to bulk water, air, water vapor, and UV light (Figure 2).

Water-resistive air barriers (WRABs)

A critical and often misunderstood component of the building envelope is the WRAB. This component may be capable of performing multiple control functions required by the building envelope.

WRABs are often constructed using manufactured sheet goods or site-applied liquid membranes, installed to prescribed thicknesses. Each method has its own application advantages and disadvantages, and is often used in combination to leverage these advantages on a project. For instance, a wall assembly may use sheet goods to wrap long straight sections of a window surround, and then apply a liquid to connect more difficult-to-wrap corners or curved sections of the opening (Figure 3).

[2]

[2]The role of a WRAB, in order of importance, is as follows:

- Provide a secondary layer of rainwater protection for water that passes through the primary layer of rainwater protection, such as cladding or veneers. To provide this protection, it is important the material itself is not affected by water, is resistant to leaks—due to penetrations (self-sealing) at fasteners—and is able to be detailed with through-wall flashings so it may evacuate accumulated water from the interior of the assembly.

- Provide a barrier to air movement across the envelope, while providing resistance to the design prescribed difference in air pressure. Some air barriers such as glass, metal pan, and rigid boards possess adequate strength to resist such air pressures on their own, but where thin sheets or liquids are incorporated into the air barrier system, they may be incapable of resisting these forces on their own. These thin barriers bring other benefits, such as water resistance and various levels of vapor permeability, to the assembly and rely on their adhesive properties to attach themselves to other materials to gain the strength of the structure or material to which they are adhered.

-

[3]

[3]Figure 3 A wall assembly may use sheet goods to wrap long straight sections of a window surround, and then apply a liquid to connect more difficult-to-wrap corners or curved sections of the opening. Provide either resistance or permeability to the water vapor, depending on the design requirements of the barrier. In a cold climate, often WRABs that are protected behind the majority of the walls insulation are designed as Class 1 vapor barriers—those that allow less than 0.1 perm or

5.72 ng/sm2Pa of water to pass per ASTM E96—while those exposed to the colder side of the walls insulation are required to be vapor permeable—those that allow more than 10 perms or 5,721 ng/sm2Pa of water to pass as per ASTM E96—as to not risk condensation occurring within the building envelope.

Bulk water, followed by air leaks that carry large amounts of water vapor, and then water vapor transported through diffusion are the three main modes of water leaks that lead to deterioration within the wall assembly.

Installing and specifying WRABs

Properly specified and installed WRABs can help protect a building envelope from premature decay, save energy, improve comfort, contribute to better air quality, and allow mechanical systems to perform optimally. Building designers should consider obtaining advice from building envelope experts, such as building science specialists or manufacturers’ technical representatives, when selecting materials for the building envelope.

Recent feedback from designers and installers of WRABs indicate the following list of the most requested performance features:

- Maximum compatibility with other products.

- High temperature stability of the installed material.

- Low temperature application of the material.

- Solutions for various UV exposures.

- Clear installation details and designer support.

- Material options to suit the project’s climate region and zone:

○ Permeable or non-permeable.

○ Self-adhered sheets or fluid-applied.

Building codes and standards

What part do building codes and standards play in ensuring the design and installation of the WRABs are considered resilient? Simply put, they do not play a role. Many may argue it is not their responsibility to ensure resiliency—after all, codes and standards have always set reasonable minimum standards. They have done this by systematically evaluating the risks and these risks have always been based on historic experience and data when it comes to weather related events. Benchmarks, such as 50- or 100-year storms, have been considered reasonable and for the most part, accurate in determining guide minimums. However, there are many that believe the trajectory of climate events is on a very steep climb to examples not seen before, so how could codes and standards keep up with such change?

However, all is not lost. There is a growing consensus that the industry needs to do better and there is a larger understanding that although no one has a crystal ball, there is some valuable input being made into predicting the events to come. Based on those models, at least there is understanding as to where things are heading, and this allows for reasonable engineering judgements to be made in preparing for resiliency.3

Currently, there are default codes and standards in place. The following list of documents provides what is currently available as reference and guidance for the design, specification, installation, and testing of air barriers:

In the U.S.:

- International Building Code (IBC)

○ Exterior Walls Chapter 14 IBC

○ Weather Protection IBC 1402.2

○ Vapor Retarders IBC 1404.3

○ Flashing IBC 1404.4

- ASTM E2178-21a, Standard Test Method for Determining Air Leakage Rate and Calculation

of Air Permeance of Building Materials - ASTM E2357-18, Standard Test Method for Determining Air Leakage Rate of Air Barrier Assemblies

In Canada:

- National Building Code of Canada (NBC)

○ Provincial building codes

○ Part 9—Small buildings

○ Part 5—Environmental separation

- CAN/ULC-S741-08(R2020)—STANDARD FOR AIR BARRIER MATERIALS—SPECIFICATION

- CAN/ULC-S742:2020—STANDARD FOR AIR BARRIER ASSEMBLIES—SPECIFICATION

Demand for resilient WRABs

The CAN/ULC-S741 and CAN/ULC-S742 standards are interesting as they are much better at evaluating both a material and an assembly’s ability to perform to ultimate limits under more realistic environmental conditions than the ASTM test methods alone. CAN/ULC-S741 and CAN/ULC-S742 rely highly upon the ASTM methodology, but have improved upon the context in which it is performed. This can assist designers and specifiers in comparing systems to better understand and select the appropriate WRAB for their project. These improvements in standards are most welcomed, but if to be fully prepared to meet the challenges of a changing climate, it is important to ensure what is specified in design is achievable and verifiable where it matters most, which is, in the built environment.

To meet the challenges of tomorrow, there is a need to bring together quality specifications and standards with clearer building code requirements that insist upon verification of both the assembly and full building performance through a well-defined commissioning process based upon the ASTM E2947-21a, Standard Guide for Building Enclosure Commissioning. It would include rigorous field testing based upon the following:

- The field adoption of ASTM D3330, Peel Adhesion Testing of Pressure Sensitive Tape

- ASTM D4541-22, Standard Test Method for Pull-Off Strength of Coatings Using Portable Adhesion Testers

- ASTM E1186, Standard Practices for Air Leakage Site Detection in Building Envelopes and Air Barrier Systems

- ASTM E3158-18, Standard Test Method for Measuring the Air Leakage Rate of a Large or Multi-zone Building

This may take great effort from all industries and influencers who are concerned with protecting the owner’s investment, but it is the appropriate choice to make. No one can assure what tomorrow will bring to the climate front, and the industry may be powerless to influence it; however, with a growing demand for resilient WRABs and structures, environments can be better prepared to face any environment.

Notes

1Read more about the effects of climate change, www.climate.nasa.gov/effects.

2Read “BSD-018: The Building Enclosure,” John Straube, August 01, 2006.

3Learn about the United Nation’s sustainable development goals, www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment.

Author

Author

- [Image]: https://www.constructionspecifier.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/01/Figure-1-Building-Science.com-Corporation.jpg

- [Image]: https://www.constructionspecifier.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/01/Figure-2-Siplast-Inc.jpg

- [Image]: https://www.constructionspecifier.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/01/Figure-3-Siplast-Inc.jpg

Source URL: https://www.constructionspecifier.com/rethinking-building-envelopes-for-climate-ready-buildings/