Role of air barriers in mitigating disease transmission

Roofs

Two basic types of roofs are used in existing buildings—steep slope and low slope. Both have challenges specific to their type, but there are also common items that could lead to issues with adding elevated interior RH. Many materials that have been used in roofs can limit air and vapor permeance, such as craft paper, some sheet goods, or even metal roof decking. However, some of these same materials have limitations regarding effectiveness to be installed in an airtight manner. If they are not airtight, they can allow humidified air to intrude into the roofing system and reach surfaces below the dewpoint. It is also important to determine whether a vapor retarder was intended to function as a part of an air barrier system, thereby precluding air movement through control layers.

Penetrations, such as pipes, drains, mechanical equipment curbs, screen wall posts, and access hatches are common locations for breeches at control layers. While these penetrations may prevent exterior rainwater penetration, they also need to be verified for limiting air, thermal, and vapor transfer before considering increasing interior RH. Figures 1 and 2 illustrate potential air paths through a low-slope roof system and the potential condensation that could result under specific operating condition.

Another consideration when evaluating the roofing assembly is whether the system was mechanically attached or adhered. Mechanically attached roofs include fasteners extending from the exterior down through the roofing assembly into the interior (Figure 3). While this type of system may perform in a low RH building, the fasteners can potentially add more paths for air migration by penetrating the air/vapor barrier membrane above the roof deck.

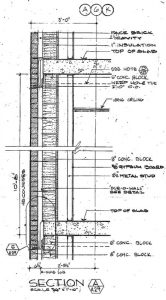

The roof-to-wall interface can also be an area for concern, and extra care should be considered should the RH be increased. For example, the material properties of the roofing membrane and the water-resistive barrier at the wall may be able to function as a part of an air barrier system, but if they are not connected in an airtight manner, moisture-laden air can exfiltrate, leading to potential condensation within the parapet.

At another common roof-to-wall condition, an interior vapor retarder was included but was not designed or installed as a part of the air barrier system. It is also not uncommon to have the perimeter structural beams very close to the exterior wall, limiting the ability to access the underside of the roof deck for termination of the vapor retarder or transition to the roof deck. The roof slab can also act as a thermal bridge, as demonstrated in Figure 4, representing a potential area for condensation under elevated RH.

Similarly, some roof parapets include curtain wall systems as part of the assembly. Vertical mullions within this assembly extend into the cold parapet area and can act as vertical thermal bridges. These thermal bridges may contribute to the surfaces of the curtain exposed to the interior to drop below the dewpoint temperature (Figure 5).

Fenestration

Like roofs and walls, numerous types of fenestration systems currently in service on existing buildings vary widely in their ability to resist condensation. These systems can range from historic, single-pane glass in non-thermally broken frames to contemporary systems. Contemporary glazing may be coated or non-coated glass, in a double- or triple-pane configurations, and they can utilize more efficient airspace gases such as argon. Modern systems may include thermally improved aluminum frames or may be more highly efficient with robust thermal breaks. Figure 6 illustrates the thermal behavior of three slightly different curtain wall systems. All three utilize the same double-pane insulated glass unit (IGU), but are modeled in three different framing systems—a non-thermal frame, a thermally improved frame, and a thermally broken frame. A high-performance curtain wall system with enhanced thermal breaks and triple-pane IGU was also modeled for comparison. Based on the estimated surface temperatures, these systems can accommodate RH levels of approximately 24, 28, 31, and 40 percent respectively, and with the exception of the high-performance option, all are below the recent guidelines outlined in the ASHRAE PD. Further, in the authors’ experiences, single-pane glass can accommodate an interior RH of 15 percent or less.