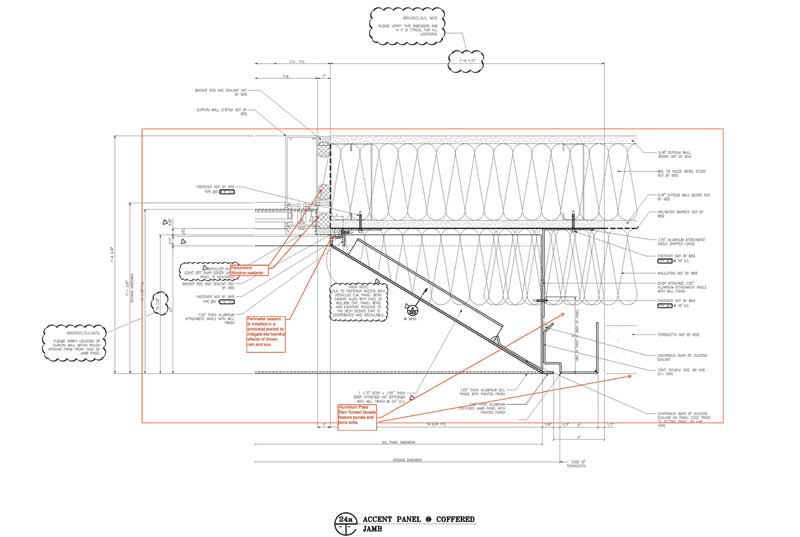

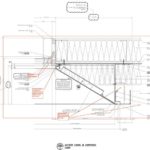

Penetrations in the air vapor barrier

Any rainscreen wall cladding design is only as good as the existing condition of the air vapor barrier system covering the drain plane. Best practice is to minimize and manage the number and type of air barrier penetrations to avoid leaks into the interior cavities of the wall system. The most successful outcomes can be achieved when the design professional identifies, details, and assigns those penetrations with the correct sealant and repair information. This should be done for each type of penetration, either through performance specifications and detailing or both. The rainscreen system should at least be specified so the exterior façade installer either controls the attachment for the secondary supports and thermal layer connections through the air barrier or the exterior façade contractor supplies/installs the project’s air barrier system in an integrated and coordinated approach with the exterior leaf rainscreen systems

(Figure 7).

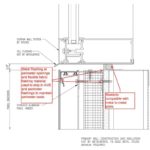

Perimeters

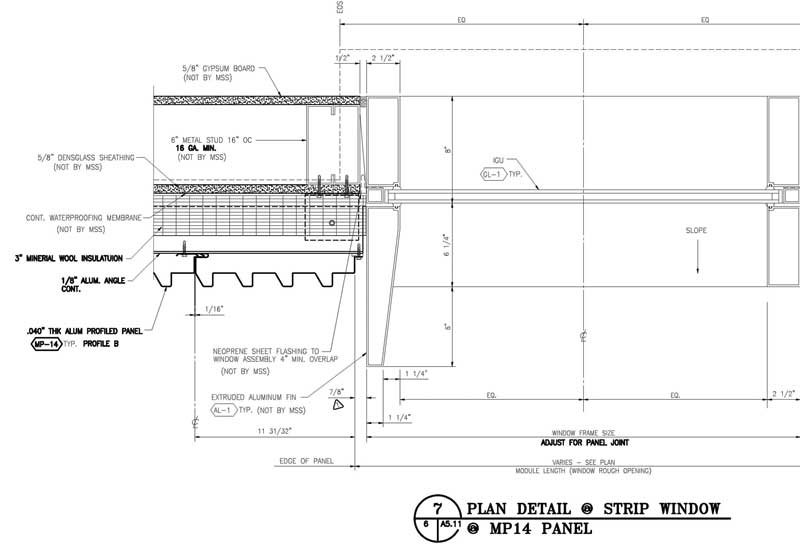

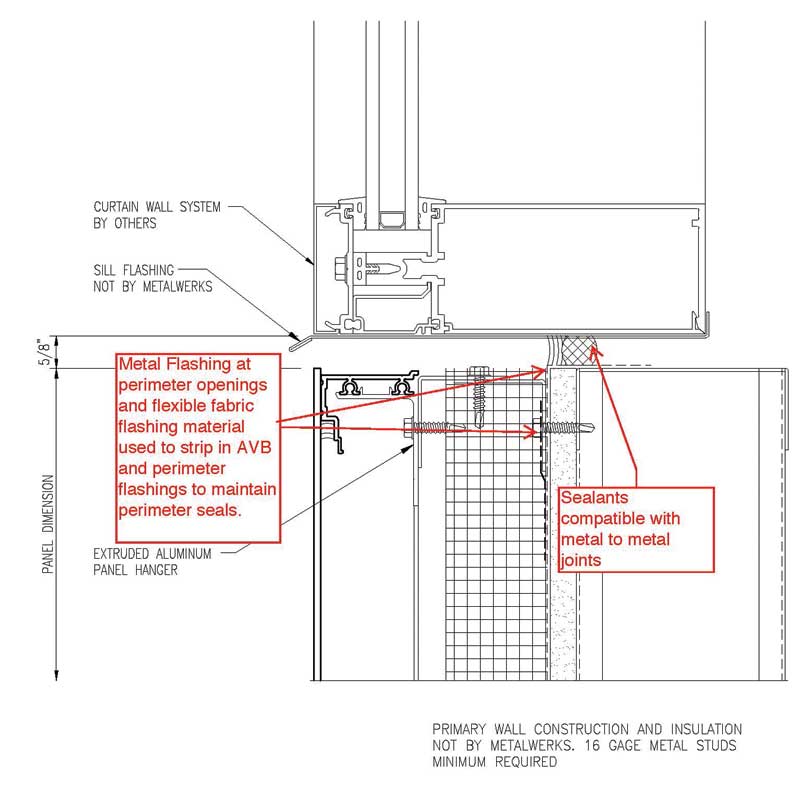

Flashing and sealants at the perimeter conditions of the metal rainscreen assemblies, which are interrupted with the fenestration (i.e. windows, louvers, doors, and curtain walls) or termination of other adjacent wall systems, is a critical weak point. The edges of the assembly are most exposed to the elements, particularly wind-driven rain. Perimeter details must be designed to:

- protect from the battering effects of wind-driven rain and UV exposure to maintain longevity (Figure 8);

- divert drain plane surface drainage from the areas above the opening or penetration, around the penetration, or toward the outer surface of the system (flash openings from the bottom up—sills and jambs should be shingled under the head conditions [Figure 9]);

- place sealants and flashing interface properly with the air barrier and

the seals for the fenestration that are independent of the rainscreen leaf elements (formed metal flashing should be ‘tied into’ or ‘stripped into’ the air barrier system with the appropriate flexible flashing or applied sealant material to maintain continuity of the air barrier and seal any fastener penetrations from the flashings [Figure 10]); - avoid sealant details applied to dissimilar materials to ensure the sealant joints are not stressed by differing adhesion properties or thermal expansion and contraction coefficients; and

- allow access to exterior sealants for future inspection and replacement (blind seals are difficult to locate, diagnose, and test in the event of a wall failure).

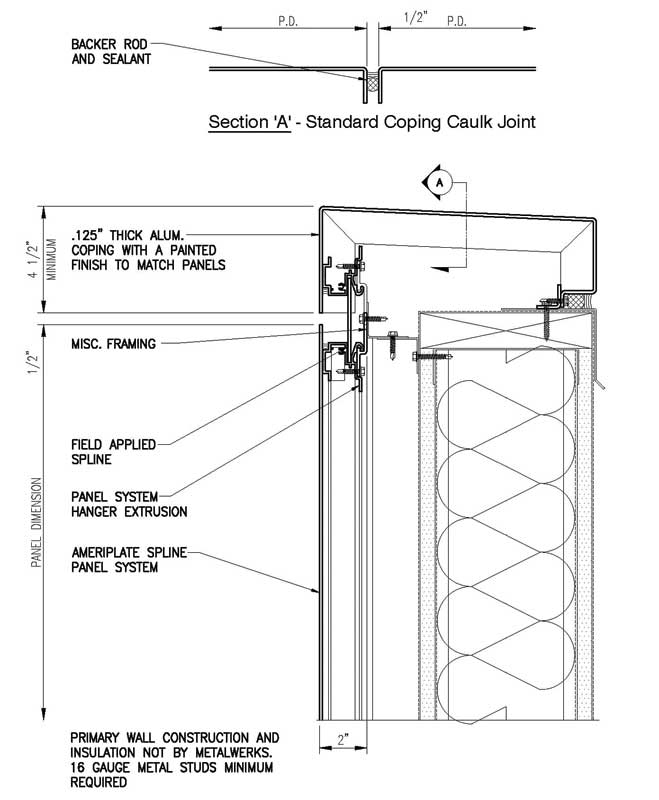

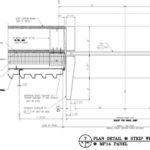

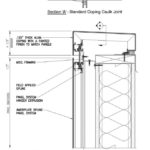

Parapets

The proper treatment of skyward-facing parapet copings or projections is a common oversight. When a designer selects a rainscreen façade system, there seems to be a temptation to design a ‘dry-joint’ parapet or brow for appearance’s sake. This practice should be avoided due to the amount of water that can enter the wall system, which must then be drained. The best technique is to continuously seal the top of the wall—preventing a buildup of water into open spaces of the system. Exposed skyward-facing joints must be sealed with an exposed sealant joint. For extra longevity and protection, a continuous substrate and flexible roof membrane can be installed under all horizontal surfaces large enough to collect rain or snow. Eventually, all sealant joints fail and render any horizontal surface vulnerable to moisture intrusion (Figure 11).

Pre-installation preparation and testing

In addition to attentive detailing and notations, performance-quality procedures must be ensured by designating a mockup area on the building, or offsite for third-party lab testing. Every project is different. Testing actual job-specific conditions is the best way to catch interferences, sequencing problems, and coordination conflicts. One can conduct iterative field-testing of in-place sample areas of work (e.g. rainscreen walls and fenestration with perimeter flashings and sealants) or lab mockups to identify trouble spots.

For a wide variety of field quality performance tests and range of project designs and budgets, one can refer to Architectural Testing Labs’ array of American Architectural Manufacturers Association (AAMA) and ASTM performance testing protocols. (Visit www.archtest.com for more information on the testing protocols.) Even a relatively inexpensive AAMA 501.2, Field Hose Test, can help identify trouble spots prior to installation. (This test method is often used on rainscreen wall projects to test the air barrier, flashing, substrates, and fenestrations as well as their perimeter conditions. It is also commonly employed in rainscreen wall assemblies, including the wall substrates, air/water barrier combination as well as any fenestration assemblies [windows, doors, and louvers] within the designated wall area. It is particularly useful to analyze the perimeter conditions as they interface with the wall assembly.) Diagnosing problems and fixes after the project is underway can cost owners a lot of time and money.

Iterative testing is important to ensure subsequent steps during the installation process do not impair or impact the performance of previously installed sub-assemblies. The author found the following iterative testing to be useful without being cost prohibitive:

- test the quality of the specified air barrier after application and cure

on a flat wall surface without any supplemental furring, anchor cleats, or perimeter flashings; - test the air barrier and penetration conditions of the assembly after installation of any components requiring attachment through the air barrier field and subsequent repairs such as furring, anchor cleats, or perimeter flashings;

- test air barrier, perimeter flashings, and sealants at one or more window areas after all field repairs of penetrations and perimeter flashings are installed and cured, also using the air barrier manufacturer’s recommended patch methods for fastener and clip penetrations; and

- test the final assembly of the rainscreen components after the installation of the insulation, decorative rainscreen trims, and rainscreen-facing panels.