Show Time: Delivering high-performance lighting for world-class museums

by Scott W. Briggs, AIA, and Steven Rosen, FIALD, IES

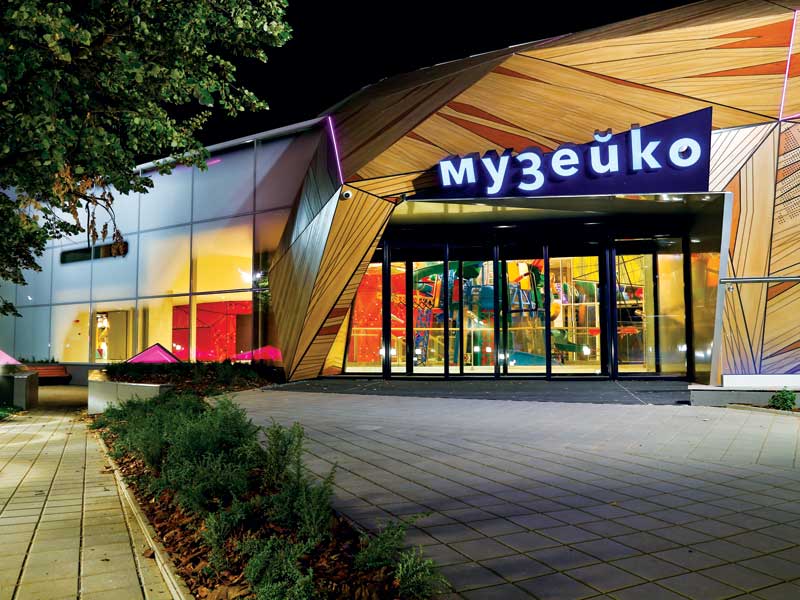

North American museums are among the world’s leaders in creating immersive and educational exhibition experiences. The technical solutions behind these multimedia environments combine expertise and creativity, and sometimes require complex electrical and lighting methods rooted in theatrical technology. Designers and specifiers of lighting for museum environments often develop custom solutions that both meet the design criteria and address all codes, standards, and best practices. Sometimes, simple, proven, and time-tested lighting applications are best. The key is to weigh the alternatives for these often-tricky situations.

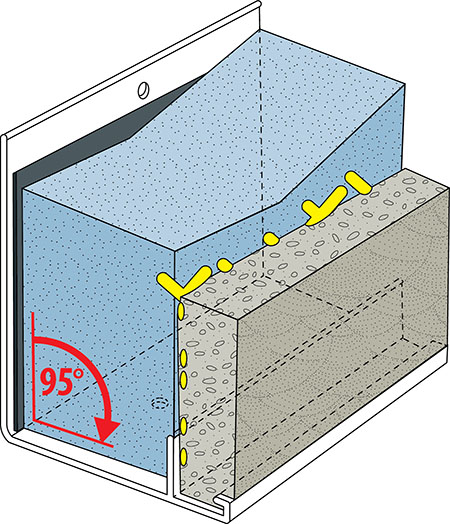

Today’s immersive museum exhibitions are often far more complex than the conventional track lighting applications typically used in art galleries. Both line-voltage and low-voltage systems can be building-mounted or integral to exhibit components, requiring careful review of the listings, ratings, and distinct installation requirements for each fixture and its support system.

For museums, these typically include exterior ratings as well as ratings for concealed and exposed lighting sources, depending on the nature of the exhibits. Electrical and lighting equipment may be recessed into the exhibit components and architectural elements, requiring hidden but accessible outlets and electrical distribution for maintenance or future changes. Some lighting fixtures, ballasts, and controls must be paired safely with exhibit materials such as wood, metal, polycarbonate, plastics, and the like. In certain cases, active cooling may be needed to offset high, localized heat loads.

It is critical to understand museum lighting and electrical systems may require an unusually large range of fixture and lamp types. A project may include daylighting as well as light-emitting diode (LED), incandescent, halogen, organic LED (OLED), fiber-optic, and neon sources. Decorative fixtures may borrow from industrial, commercial, and residential applications. The architect and lighting designer can manipulate several basic aspects of illumination—intensity, angle, distribution, color, and movement—to improve the visitor’s ability to interact with and understand the exhibition content. When approaching exhibition work, the lighting designer’s objective may be to create an immersive environment that seeks to subliminally draw the visitor into the experience, thus encouraging further learning opportunities.

Most importantly, the design team must measure the color of light using the color rendering index (CRI), which describes the light source’s ability to reproduce colors of illuminated objects. The Illuminating Engineering Society of North America (IES) TM-30, Method for Evaluating Light Source Color Rendition, is a newer and more accurate measure of color rendering ability, especially for LEDs. A CRI of greater than 90 is considered ‘high-CRI,’ and may be required for museum exhibitions. In many cases, a physical mockup of the particular lighting situation is often required to test not only the color of the light, but also the effectiveness of the lighting solution on an exhibit’s intended presentation and function.

In all cases, there is a desire to specify energy-saving solutions; state-of-the-art LED systems can offer up significant efficiencies.

“Museums have become an important test bed for these lighting technologies because museums demand the highest quality and employ full-time professional lighting staff that maintain quality over time,” says Scott Rosenfeld, a lighting designer with the Smithsonian American Art Museum.

LED sources can improve the visitor experience, he adds, while also minimizing the damaging effects on light-sensitive materials. In some of his museum facilities, Rosenfeld has cut energy costs by 70 percent with lighting quality comparable to legacy incandescent lighting. (For more, visit www.conservators-converse.org/2014/05/lighting-art-and-the-art-of-lighting).

However, most museums lack the luxury of dedicated lighting maintenance staff. In almost all cases, every lighting specification choice is driven in some manner by the knowledge only ‘near-bulletproof’ solutions are acceptable.

Adding an element of theater

Nevertheless, today’s exhibition environments can be dramatic, dynamic, and entertaining. In fact, the use of theatrical lighting technology can be quite common in thematic museum exhibits. These are used for various reasons, but mainly to impact mood and direct visitor focus, while also allowing for selective visibility and altering the perceived form of exhibit elements.

Stage lighting equipment can include a variety of light sources—LED, high-intensity discharge (HID), incandescent lamps, and fiber-optic—deployed in various luminaires, floodlights, and spotlights that can provide a number of specialty features such as beam focus, projected patterns (i.e. gobos), and beam shaping (e.g. shutters and barn doors).