Show Time: Delivering high-performance lighting for world-class museums

by Katie Daniel | April 28, 2016 10:50 am

by Scott W. Briggs, AIA, and Steven Rosen, FIALD, IES

North American museums are among the world’s leaders in creating immersive and educational exhibition experiences. The technical solutions behind these multimedia environments combine expertise and creativity, and sometimes require complex electrical and lighting methods rooted in theatrical technology. Designers and specifiers of lighting for museum environments often develop custom solutions that both meet the design criteria and address all codes, standards, and best practices. Sometimes, simple, proven, and time-tested lighting applications are best. The key is to weigh the alternatives for these often-tricky situations.

Today’s immersive museum exhibitions are often far more complex than the conventional track lighting applications typically used in art galleries. Both line-voltage and low-voltage systems can be building-mounted or integral to exhibit components, requiring careful review of the listings, ratings, and distinct installation requirements for each fixture and its support system.

For museums, these typically include exterior ratings as well as ratings for concealed and exposed lighting sources, depending on the nature of the exhibits. Electrical and lighting equipment may be recessed into the exhibit components and architectural elements, requiring hidden but accessible outlets and electrical distribution for maintenance or future changes. Some lighting fixtures, ballasts, and controls must be paired safely with exhibit materials such as wood, metal, polycarbonate, plastics, and the like. In certain cases, active cooling may be needed to offset high, localized heat loads.

It is critical to understand museum lighting and electrical systems may require an unusually large range of fixture and lamp types. A project may include daylighting as well as light-emitting diode (LED), incandescent, halogen, organic LED (OLED), fiber-optic, and neon sources. Decorative fixtures may borrow from industrial, commercial, and residential applications. The architect and lighting designer can manipulate several basic aspects of illumination—intensity, angle, distribution, color, and movement—to improve the visitor’s ability to interact with and understand the exhibition content. When approaching exhibition work, the lighting designer’s objective may be to create an immersive environment that seeks to subliminally draw the visitor into the experience, thus encouraging further learning opportunities.

Most importantly, the design team must measure the color of light using the color rendering index (CRI), which describes the light source’s ability to reproduce colors of illuminated objects. The Illuminating Engineering Society of North America (IES) TM-30, Method for Evaluating Light Source Color Rendition, is a newer and more accurate measure of color rendering ability, especially for LEDs. A CRI of greater than 90 is considered ‘high-CRI,’ and may be required for museum exhibitions. In many cases, a physical mockup of the particular lighting situation is often required to test not only the color of the light, but also the effectiveness of the lighting solution on an exhibit’s intended presentation and function.

In all cases, there is a desire to specify energy-saving solutions; state-of-the-art LED systems can offer up significant efficiencies.

“Museums have become an important test bed for these lighting technologies because museums demand the highest quality and employ full-time professional lighting staff that maintain quality over time,” says Scott Rosenfeld, a lighting designer with the Smithsonian American Art Museum.

LED sources can improve the visitor experience, he adds, while also minimizing the damaging effects on light-sensitive materials. In some of his museum facilities, Rosenfeld has cut energy costs by 70 percent with lighting quality comparable to legacy incandescent lighting. (For more, visit www.conservators-converse.org/2014/05/lighting-art-and-the-art-of-lighting[1]).

However, most museums lack the luxury of dedicated lighting maintenance staff. In almost all cases, every lighting specification choice is driven in some manner by the knowledge only ‘near-bulletproof’ solutions are acceptable.

Adding an element of theater

Nevertheless, today’s exhibition environments can be dramatic, dynamic, and entertaining. In fact, the use of theatrical lighting technology can be quite common in thematic museum exhibits. These are used for various reasons, but mainly to impact mood and direct visitor focus, while also allowing for selective visibility and altering the perceived form of exhibit elements.

Stage lighting equipment can include a variety of light sources—LED, high-intensity discharge (HID), incandescent lamps, and fiber-optic—deployed in various luminaires, floodlights, and spotlights that can provide a number of specialty features such as beam focus, projected patterns (i.e. gobos), and beam shaping (e.g. shutters and barn doors).

Photos courtesy Lee H. Skolnick Architecture + Design Partnership

In many instances, the exhibit or thematic lighting provides enough general illumination to serve ambient needs. Photometric calculations can confirm whether this layer of light can be the sole source of lighting required for such areas as key circulation paths or entrance vestibules, which can require more uniform illumination. The same is true for spaces with major exhibits that serve as focal points. More traditional architectural lighting solutions (e.g. recessed, surface, or pendant-mounted fixtures) may be employed to graze or wash architectural surfaces to illuminate a particular feature or object, create visual depth, or highlight the textural dimension of these surfaces.

Further, indirect lighting may provide illumination upward to be reflected off a ceiling plane. Often, especially when light is reflected off vertical surfaces, these techniques create a perception of brightness and expand the visual horizon of the architectural or exhibition interior in an efficient manner, while allowing the exhibits to remain the focal point of the space.

There are other considerations in museum lighting specification. For example, exhibits usually require specialty custom fabrication with integrated lighting—raising new challenges for meeting codes and obtaining jurisdictional approvals. Another is the use of interactive effects, such as switches for visitor participation with an interactive station, or occupancy sensors that activate lighting when visitors are in a viewing zone. Additionally, lighting is frequently integrated with related technologies, such as computer displays and video projections, which may be sensitive to veiling reflections and over-illumination. Still, codes and common-sense safety considerations dictate a minimum level of illumination, measured in foot-candles or lumens per square foot (lm/sf) or in lux (lm/m2), in all areas of the exhibition venue.

Science center for children

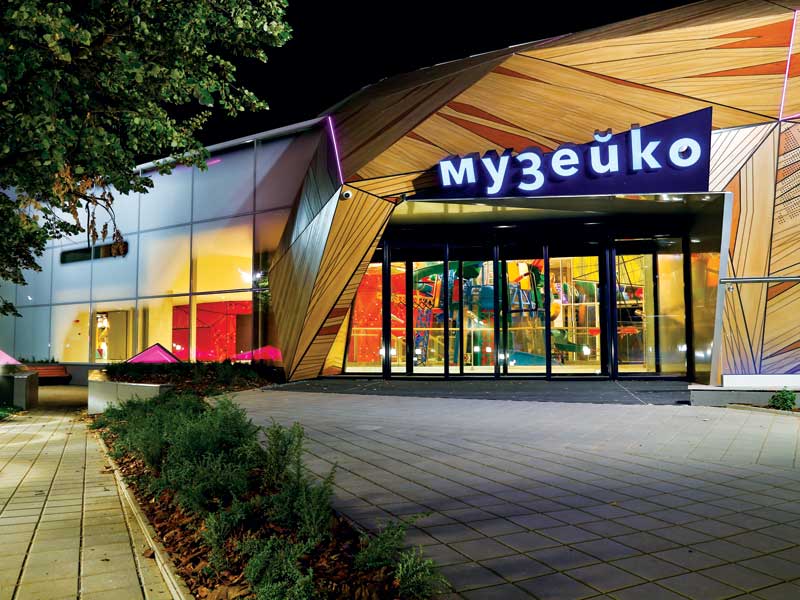

To become familiar with these rules of thumb and specification approaches, one can learn from recent and state-of-the-art applications to illustrate their impact. Drawing from our recent work on projects such as Muzeiko (a children’s science center in Sofia, Bulgaria), valuable design ideas and specification tips emerge. Other recent project collaborations between the authors’ firms include the Sony Wonder Technology Lab in Manhattan, and the East Hampton Library in East Hampton, New York.

In all cases, the design team can separately consider architectural lighting and exhibit lighting. Although each layer serves different functions, they are critically linked and are highly integral to the visitor experience. Generally, both are subject to code guidelines and enforcement in such areas as general circulation systems, specialty areas, and accent systems for proper illuminance, electrical distribution, and power densities.

The architectural layer of lighting in an exhibit gallery serves several functions, including providing for cleaning and maintenance, security, and also emergency egress. These fixtures are tied into the building lighting control system, which, in turn, responds to commands from the building management system (BMS), triggering the lights to illuminate in an emergency scenario for instance.

At most museums, emergency fixtures are not illuminated during visitor hours unless triggered by the BMS to responds to an emergency situation. In Muzeiko’s case, the gallery ceiling heights were approximately 3.1 m (10 ft) above finished floor (AFF), so a low-profile, surface-mounted LED luminaire was specified to help reduce the visual presence of this layer in the gallery space.

The project’s design firm, Lee H. Skolnick Architecture + Design Partnership, delivered site selection and design, architecture, programming and educational consulting, and exhibition design, as well as brand identity, graphic design, and signage design. This allowed a high degree of integration between often-separate design tasks.

Evoking transparency and lightness, the glass façades allow a high level of natural daylighting into the lobby and amenity spaces of the museum and permit views of the museum’s various offerings to passersby outside. Three colorful volumes, clad with custom-printed graphics on high-pressure laminate panels, suggest the mountains ringing the host city of Sofia. The three interior levels are full of highly immersive exhibits that transport children underground into the earth on the lowest level, out into the natural world on the main level and ultimately into outer space on the uppermost level of the museum.

The exhibit lighting design strategy combines dramatic, high-contrast lighting with concealed lighting, thematic effect lighting, and decorative (yet functional) fixtures.

Examining various types of architectural and exhibition lighting

Though located in Europe, for exhibit lighting sources, the children’s science center is typical of best-practice U.S. venues. As in many such projects, the push to use efficient LEDs is often restrained by the need for solutions more appropriate for the given application or effect. Here, Available Light employed LED sources for general track spot and wash lighting, as well as for mini-downlights in some headers and ceilings.

As many LED sources can be specified in a native color of light, LED lamps are well-suited to colored lighting applications, and blue PAR38 LEDs are used to illuminate the walls and interiors of several exhibits, including an outer space-themed area. (PAR stands for ‘parabolic aluminized reflector,’ and it is a widely used source in commercial and institutional projects—the number indicates the diameter of the housing in eighths of an inch). Red and amber LED PAR38s create an intense colored effect to illuminate the simulated surface of Mars for an interactive rover activity at Muzeiko. A large ‘tree’ display creates a signature element in the museum’s lobby. Comprising varied materials such as steel, acrylic, and plastics, green LED PAR lamps housed within cylindrical fixtures to mask the lamps from view, shine down through its ‘leaves,’ which are suspended hexagonal green acrylic panels.

The PAR38 LEDs use only about 16 watts, and are rated to last 30,000 hours, or about 27.4 years. In some places, these lamps can be clustered to create areas of intense illumination or other effects. Combo LED fixtures are arrays of LED sources in a single housing, and may have three sources or up to 80 or more. These can be recessed into walls for general illumination.

Smaller-profile LED fixtures can be used behind and under exhibits, such as beneath a glass walkway in Muzeiko’s cave exhibit. At the science museum, another type—narrow-beam LED track fixtures—produces dramatic high-contrast shafts of light. The layouts of the overhead fixtures often mimic the shapes of the architecture or exhibit envelope. One such application at Muzeiko recesses these fixtures in the varied faceted planes of the dome-like lobby ceiling.

When the science center lighting was originally specified in 2013, some LED technologies related to museum exhibition lighting were still in their infancy, so many of those primary light sources were specified as low-wattage ceramic metal halide (CMH), which is a type of HID source. These sources are significantly more efficient than traditional tungsten halogen lamps; like LEDs, however, they deliver excellent color rendition—about 80 to 96 CRI, according to a specialty fixture manufacturer the authors consulted.

As controlling color temperature is among the most important aspects of museum exhibition lighting selection, fixtures with high CRI are often critical to the design and specification of art galleries and other sensitive installations. In some cases, holding the spec on the CRI may be more important than holding the actual fixture spec.

Special conditions and details

Another way exhibition lighting may greatly differ from art gallery lighting is in its use of concealed, special effect, and thematic fixtures. The listings and ratings for these fixtures may vary significantly from standard lighting products, and specification teams should carefully review the manufacturer data and confirm the product’s track record.

Museums tend to prefer ‘set-and-forget-fixtures that require minimal maintenance and relamping. For LEDs, thermal management (i.e. efficient removal of heat generated at the point where the LED chip is mounted to a substrate) is vital to fixture longevity; poorly designed fixtures and installations can cut LED chip lifespan by as much as 80 percent.

For CRI, good manufacturers provide verified photometric test results. Safety certifications include UL listing and hazardous substance registries such as Electronic Waste Recycling Act (EWRA) in the United States and Restriction of Hazardous Substances (RoHS) directive in the European Union. Test reports must verify claims of brightness and longevity, such as IES LM-79, Approved Method for the Electrical and Photometric Measurements of Solid-state Lighting Products. Also vital to performance is the quality of the materials, such as the thickness and componentry used in wires, reflectors, and housings.

Concealed fixture applications in museum exhibitions may include backlit substrate and see-through conditions, as well as fixtures in the floor assembly for uplighting exhibits and signage above or overhead. At the children’s science center, the design called for dozens of lamps hidden in the faux tree to light up key features. Some of these were color-changing sources or fixtures, which add the effect of animation to the whole tree, with sweeps of color passing over in a coordinated sequence. Another tool used is the wire coil fixture spiraling around the upper limbs; it is made of electroluminescent (EL) wire in various static colors.

Photo © Roland Halbe. Photo courtesy Lee H. Skolnick Architecture + Design Partnership

Exhibition designers and architects may create designs that call for novel or unexpected techniques to achieve results. Some may include traditional incandescent sources, or use of LED strips or tape lights, as well as window lighting, and other indoor/outdoor exterior lighting methods. At the children’s science museum, for example, a blue uplight was employed on a ceiling surface to create the illusion of distant outer space. An effective way to mark the entry points of an exhibit space is to place decorative pendants that can have either color-changing lights or thematically derived forms that fit the exhibit content and messaging.

Specialty and decorative fixtures can enhance the exhibit themes. For example, actual work lights used for mining and cave exploration add a particular touch of realism to the museum’s underground exhibit environment. Period cage-style lights provide a retro look, while new style LED work lights suggest a more contemporary workspace. Muzeiko also features industrial ‘jelly jar’ work light fixtures, as well as oil lanterns custom fitted with LED lamps, pendant mounted from an archaeologist’s field tent structure to provide dramatic, high-contrast lighting. Other decorative fixtures and lamps may include pendants with:

- conductors, cables, and ballasts;

- raceway, boxes, and connections; and

- low-voltage distribution systems.

Local controllers such as occupancy sensors may be integral to wall-mounted switches, but in museums, switches are typically hidden from use by the visiting public. Occupancy sensors for special effects are common, but increasingly museum operators are using ‘instant-on’ exhibits that help save energy.

In locations such as admissions counters, foodservice, and information areas, good general illumination is needed, which may be fluorescent or LED pendants, recessed fixtures, or sconces. Museum shops employ best-practice retail lighting technology, with several layers of light to ensure a comfortable environment for shoppers to browse.

Pendant or surface-mounted electrified lighting tracks host LED or HID track fixtures. Attributes like fixture-position locking, optical beam-shaping lenses, and also glare control accessories help ensure a glare-free experience for the visitor. The potential exists for small-scale LED lighting to be integrated into the millwork, increasing prominence in the retail space.

Photo courtesy Lee H. Skolnick Architecture + Design Partnership

The trickiest areas for specifiers, however, are the exhibitions.

“These environments and venues are out of the norm,” says Lee H. Skolnick, FAIA, who has designed more than 50 exhibits or museums for children and is the author of What Is Exhibition Design? “They’re not typical white-box galleries that are used for art and the like. However, there is really less mystery in them than most architects and designers think.”

Still, Skolnick cautions even experienced contractors and installers might need extra guidance on today’s lighting and control systems. Engaging the services of a theatrical lighting integrator can save enormous amounts of time, money, and grief. Coordination and planning may be complex and require several mockups for proof of concept. Long-lead items can include specialty and high-performance electrical fixtures, making proper scheduling essential. Additionally, project commissioning and handoff to the museum’s operators is a critical process.

In all cases, early involvement of lighting designer and exhibition fabricator is encouraged. Typically, exhibit lighting designers are best engaged early in the design process at the schematic design (SD) or design development (DD) phase. Although a large part of the lighting designer’s responsibilities is technical in nature, an equal part of the design equation is the creative input a lighting designer can provide as part of the architectural or exhibit designer’s creative team. Use of mockups for some challenging exhibits will also smooth the design and construction process.

Particularly for international projects like Muzeiko, a U.S. design team may have a limited role, working only through the DD phase. However, in all cases, the construction documentation (CDs) and well-crafted specifications are the key to communicating desired design concepts and applications of the electrical and lighting products. Downstream substitutions, ‘value-engineering,’ and change orders are a challenge in all projects, but the best museum exhibitions are places where the specifier team stood firm and held the specs.

Scott W. Briggs, AIA, is a senior associate in Museum Services with Lee H. Skolnick Architecture + Design Partnership (LHSA+DP), a multidisciplinary firm based in New York City that specializes in education, museum and corporate facilities, exhibits, interactive experiences, and graphic identity. He can be contacted via e-mail at sbriggs@skolnick.com[2].

Steven Rosen, FIALD, IES, is president and creative director of Available Light, a lighting design firm specializing in museum exhibitions, architecture, trade shows, and special events. Since its founding in 1990, the firm has designed lighting for such diverse projects as medical centers, marine museums, five-star hotels, and fashion industry events. He can be reached at steven@availablelight.com[3].

- www.conservators-converse.org/2014/05/lighting-art-and-the-art-of-lighting: http://www.conservators-converse.org/2014/05/lighting-art-and-the-art-of-lighting

- sbriggs@skolnick.com: mailto:sbriggs@skolnick.com

- steven@availablelight.com: mailto:steven@availablelight.com

Source URL: https://www.constructionspecifier.com/show-time-delivering-high-performance-lighting-for-world-class-museums/