Sizing pipes: Exploring CPVC as a material alternative

Selecting pipes

Taking the knowns (i.e. friction losses, pressure drops, supply pressure, and the number of fixtures), code tables will indicate the flow rate (demand) needed to feed those fixture units. This rate enables the designer to determine what size pipe is required to achieve the proper flow rate to feed those fixtures.

Material considerations

Pipe materials are among other factors impacting pressure loss calculations. While traditional copper tubes and alternative cross-linked polyethylene (PEX) have the same outside diameters as copper tube size (CTS) CPVC assemblies, the materials themselves require different wall thicknesses to meet standardized pressure ratings (copper is thinnest, while PEX is thickest). Therefore, if the water flow is consistent, the velocity and pressure loss would be greatest with a PEX system (due to its smaller internal diameter) and a larger pipe size might be required to maintain the necessary residual pressure at the farthest fixture.

When compared to CPVC, the flexibility of PEX may reduce the number of fittings, but the pressure drop through a CPVC fitting is less than a comparable PEX fitting. While CPVC and copper fittings surround the exterior of the pipe, PEX fittings are inserts, which create orifices in the piping systems and restrict flow.

As copper corrodes and its surface becomes rougher, this material can also experience some pressure drop over time. This drop is calculated using the Hazen Williams C-Factor Assessment (C-Factor), which is a constant that applies to the pipe related to smoothness. Under this assessment, a higher number denotes a smoother pipe. At their origin, steel has a C-Factor of 120, whereas PEX, CPVC, and copper are each valued at 150. However, copper’s C-Factor decreases over time as the material scales and corrodes—CPVC’s assessment remains constant.

Sizing a system

Another challenge when selecting pipes is oversizing the system. At times, sizing tables do not offer the necessary granularity to accurately design a system. In these circumstances, it is best practice to select a larger pipe size to ensure required demand is met with excess capacity. However, this results in greater expense and wasted water, which is a growing national concern.

Small pipes can be used to push water through very quickly, but this is not necessarily feasible for a few reasons. First, because there is more friction, this process introduces the potential for erosion in copper pipes, which, depending on the size of the pipe, are generally limited to 1.5 m (5 ft) per second for hot water and 2.4 to 3 m (8 to 10 ft) per second for hot and cold.

Second, this method can lead to a water hammer—a loud knocking noise in a pipe when water is turned off. In devices with a quick-closing valve (i.e. a washing machine or an ice-maker), water goes from moving 2.1 m (7 ft) per second to a near-immediate complete stop, creating a pressure wave in the pipe. Generally, the peak pressure wave should not exceed 1.5 times the maximum operating pressure of the pipe experiencing the pressure wave. The pipe should be properly sized to avoid exceeding this limit.

Under some regional codes, water hammer arrestors are required to absorb the pressure wave before it travels down the pipe. To be effective, these devices must be placed as close to the quick-closing valve as possible. Even if the pressure wave does not exceed 1.5 times the maximum operating pressure, the wave can still create unacceptable noise in the system.3 Pressure-arrestors, which are often installed in retrofits, can dampen this noise.

Expansion loops

It is also important for professionals to consider expansion loops. As with all building materials, CPVC pipes expand when heated and contract when cooled. Engineers must factor this expansion into the system design.

CPVC expands about 25 mm (1 in.) per 15 m (50 ft) of length when subjected to a 28 C (50 F) temperature increase. Linear expansion does not vary with pipe size. Although expansion is primarily a concern on hot water lines, expansion allowances for hot or cold water pipes installed in unconditioned spaces should account for the temperature difference between the installed temperature and the service temperature.

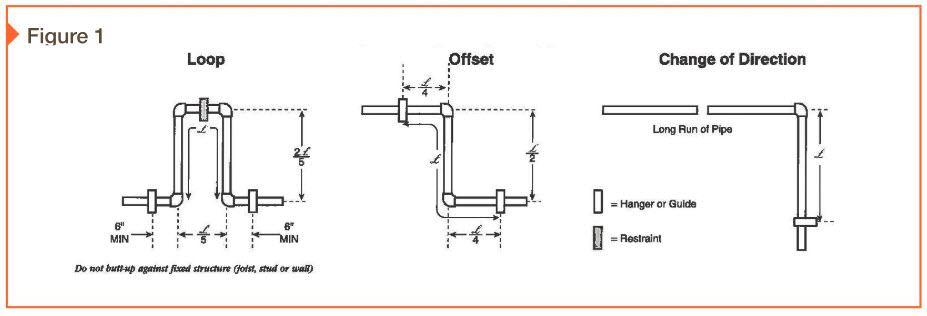

Expansion loop requirements for CPVC are similar to those of properly designed copper systems. Generally, the effects of expansion can be controlled with changes in direction; an offset or loop may be required on a long straight run. One properly sized expansion loop (Figure 1) is all that is required in any single straight run of pipe, but two or more smaller expansion loops, properly sized, could also be used. Pipes should be hung with smooth straps that will not restrict movement—the pipe must be free to move for the expansion loops to work.

Per International Association of Plumbing and Mechanical Officials (IAPMO) IS 20, CPVC Solvent Cemented Hot and Cold Water Distribution Systems, expansion loops are not required in vertical risers, provided the temperature change does not exceed 67 C (120 F). To allow for expansion and contraction, vertical piping must be supported at each floor as specified by the design engineer and piping should have a mid-story guide. Engineers should use hangers and straps that do not distort, cut, or abrade the piping.

No matter the material or the project type, professionals should always consult with pipe manufacturers for special considerations and installation/engineering requirements.