Sizing pipes: Exploring CPVC as a material alternative

by Sarah Said | September 21, 2018 2:38 pm

by Tom Attenweiler and Don Townley

[1]

[1]Sizing a water distribution system for a commercial space requires consideration of several factors—from pressure to fixture count to pipe material. Calculating all contributing factors is essential to meeting code requirements as well as ensuring proper operation of the system.

This article focuses particularly on chlorinated polyvinyl chloride (CPVC)—a semi-rigid material providing pipes that are versatile, durable, and cost-efficient, making them well-suited for both commercial and industrial applications.

Pipe sizing considerations

The first step in pipe sizing for commercial structures is determining the water pressure entering the building from the city. There is pressure regulation at the water meter, which is where engineers and designers start tabulating friction losses contributing to a system.

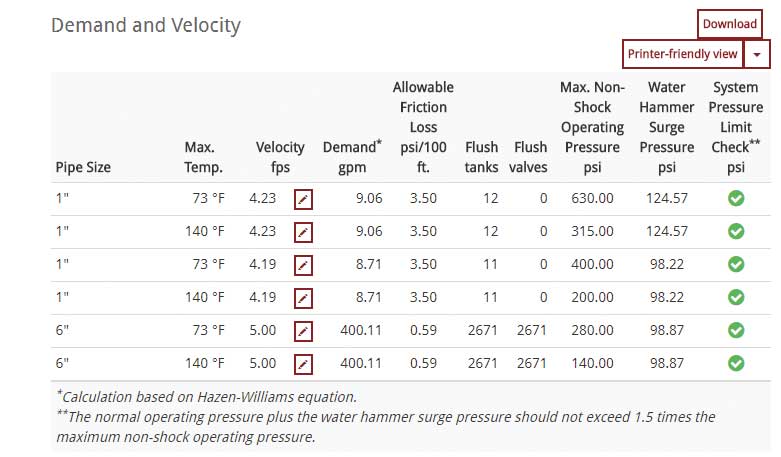

Understanding these losses enables the designer to translate them into an average pressure drop per 30.5 m (100 ft) for the system. This drop is a fundamental parameter required for calculation of the system velocity and, ultimately, the flow rate (or “demand”).

Plumbing codes establish guidance for the number of fixture units serviced by a given flow rate. In addition to its dependence on pressure drop, flow rate also relies on the inner diameter of the pipe. Due to this relationship, the size of the pipe can be adjusted to achieve the necessary flow rate required to service the desired number of fixture units. However, the maximum number of fixture units capable of being serviced depends on the available pressure in the system.

Pressure coming into the system is typically limited by local plumbing codes to 552 kPa (80 psi), although most systems average around 275 to 345 kPa (40 to 50 psi). Other factors, including altitude, may also come into play. Generally, the pressure needs to remain around 103 kPa (15 psi) once it reaches each fixture.

Determining if this pressure will be reached requires adding up the friction losses in the system. This can either be achieved manually or through use of a sizing calculator, whereby a designer inputs incoming pressure and then lists known pressure losses. Every element in the water system, from the meter to a bend, results in pressure losses.

[2]

[2]Typical friction losses/gains include:

- water meters;

- pressure-reducing valves;

- submeters; and

- elevation loss/gain.

After tabulating friction losses, a designer can determine the total pressure drop, which is then reported on building plans.

Pipe size selection is outlined in the International Plumbing Code (IPC):1

Water pipe sizing procedures are based on a system of pressure requirements and losses, the sum of which must not exceed the minimum pressure available at the supply source. The pressures are as follows:

- Pressure required at fixture to produce required flow.2

- Static pressure loss or gain (due to head) is computed at 0.433 psi/ft (9.8 kPa/m) of elevation change.

e.g. Assume that the highest fixture supply outlet is 20 ft (6096 mm) above or below the supply source. This produces a static pressure differential of 20 ft by 0.433 psi/ft (2096 mm by 9.8 kPa/m) and an 8.66 psi (59.8 kPa) loss. - Loss through water meter. The friction or pressure loss can be obtained from meter manufacturers.

- Loss through taps in water main.

- Losses through special devices such as filters, softeners, backflow prevention devices, and pressure regulators. These values must be obtained from the manufacturers.

- Loss through valves and fittings. Losses for these items are calculated by converting to equivalent length of piping and adding to the total pipe length.

- Loss due to pipe friction can be calculated when the pipe size, the pipe length, and the flow through the pipe are known. With these three items, the friction loss can be determined. For piping flow charts not included, use manufacturers’ tables and velocity recommendations.

[3]

[3]Selecting pipes

Taking the knowns (i.e. friction losses, pressure drops, supply pressure, and the number of fixtures), code tables will indicate the flow rate (demand) needed to feed those fixture units. This rate enables the designer to determine what size pipe is required to achieve the proper flow rate to feed those fixtures.

Material considerations

Pipe materials are among other factors impacting pressure loss calculations. While traditional copper tubes and alternative cross-linked polyethylene (PEX) have the same outside diameters as copper tube size (CTS) CPVC assemblies, the materials themselves require different wall thicknesses to meet standardized pressure ratings (copper is thinnest, while PEX is thickest). Therefore, if the water flow is consistent, the velocity and pressure loss would be greatest with a PEX system (due to its smaller internal diameter) and a larger pipe size might be required to maintain the necessary residual pressure at the farthest fixture.

When compared to CPVC, the flexibility of PEX may reduce the number of fittings, but the pressure drop through a CPVC fitting is less than a comparable PEX fitting. While CPVC and copper fittings surround the exterior of the pipe, PEX fittings are inserts, which create orifices in the piping systems and restrict flow.

As copper corrodes and its surface becomes rougher, this material can also experience some pressure drop over time. This drop is calculated using the Hazen Williams C-Factor Assessment (C-Factor), which is a constant that applies to the pipe related to smoothness. Under this assessment, a higher number denotes a smoother pipe. At their origin, steel has a C-Factor of 120, whereas PEX, CPVC, and copper are each valued at 150. However, copper’s C-Factor decreases over time as the material scales and corrodes—CPVC’s assessment remains constant.

Sizing a system

Another challenge when selecting pipes is oversizing the system. At times, sizing tables do not offer the necessary granularity to accurately design a system. In these circumstances, it is best practice to select a larger pipe size to ensure required demand is met with excess capacity. However, this results in greater expense and wasted water, which is a growing national concern.

Small pipes can be used to push water through very quickly, but this is not necessarily feasible for a few reasons. First, because there is more friction, this process introduces the potential for erosion in copper pipes, which, depending on the size of the pipe, are generally limited to 1.5 m (5 ft) per second for hot water and 2.4 to 3 m (8 to 10 ft) per second for hot and cold.

Second, this method can lead to a water hammer—a loud knocking noise in a pipe when water is turned off. In devices with a quick-closing valve (i.e. a washing machine or an ice-maker), water goes from moving 2.1 m (7 ft) per second to a near-immediate complete stop, creating a pressure wave in the pipe. Generally, the peak pressure wave should not exceed 1.5 times the maximum operating pressure of the pipe experiencing the pressure wave. The pipe should be properly sized to avoid exceeding this limit.

Under some regional codes, water hammer arrestors are required to absorb the pressure wave before it travels down the pipe. To be effective, these devices must be placed as close to the quick-closing valve as possible. Even if the pressure wave does not exceed 1.5 times the maximum operating pressure, the wave can still create unacceptable noise in the system.3 Pressure-arrestors, which are often installed in retrofits, can dampen this noise.

[4]

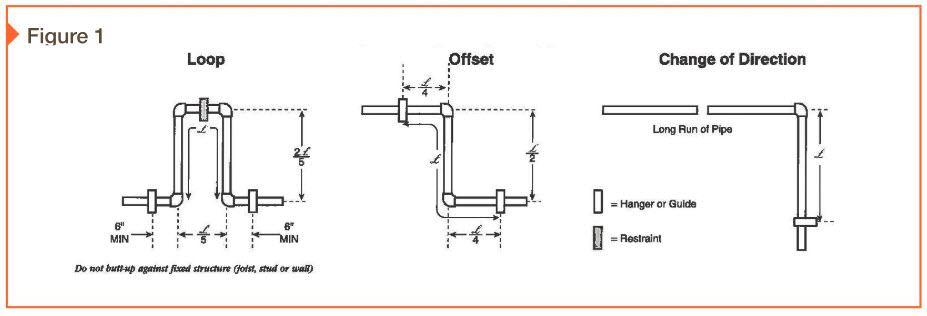

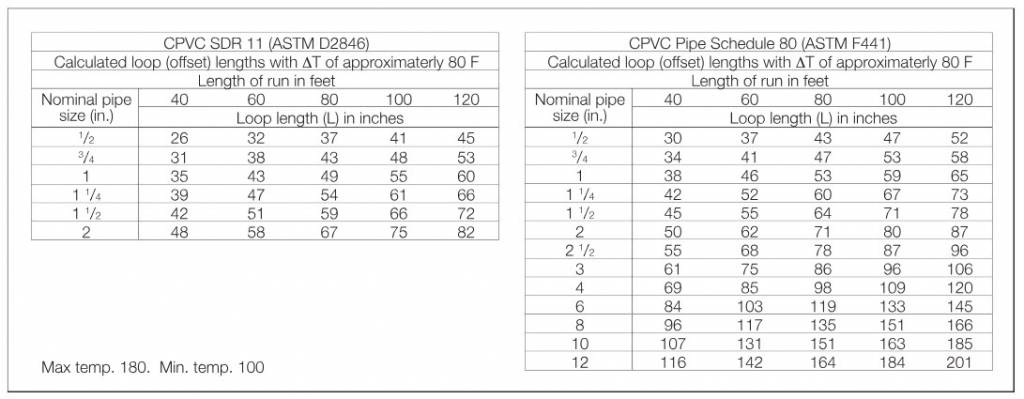

[4]Expansion loops

It is also important for professionals to consider expansion loops. As with all building materials, CPVC pipes expand when heated and contract when cooled. Engineers must factor this expansion into the system design.

CPVC expands about 25 mm (1 in.) per 15 m (50 ft) of length when subjected to a 28 C (50 F) temperature increase. Linear expansion does not vary with pipe size. Although expansion is primarily a concern on hot water lines, expansion allowances for hot or cold water pipes installed in unconditioned spaces should account for the temperature difference between the installed temperature and the service temperature.

Expansion loop requirements for CPVC are similar to those of properly designed copper systems. Generally, the effects of expansion can be controlled with changes in direction; an offset or loop may be required on a long straight run. One properly sized expansion loop (Figure 1) is all that is required in any single straight run of pipe, but two or more smaller expansion loops, properly sized, could also be used. Pipes should be hung with smooth straps that will not restrict movement—the pipe must be free to move for the expansion loops to work.

Per International Association of Plumbing and Mechanical Officials (IAPMO) IS 20, CPVC Solvent Cemented Hot and Cold Water Distribution Systems, expansion loops are not required in vertical risers, provided the temperature change does not exceed 67 C (120 F). To allow for expansion and contraction, vertical piping must be supported at each floor as specified by the design engineer and piping should have a mid-story guide. Engineers should use hangers and straps that do not distort, cut, or abrade the piping.

No matter the material or the project type, professionals should always consult with pipe manufacturers for special considerations and installation/engineering requirements.

Understanding CPVC

CPVC is particularly suited for commercial applications (e.g. schools, office buildings, retail, and hospitals), as well as industrial applications (e.g. chemical processing, manufacturing, mineral processing, wastewater treatment, power generation, and marine applications).

The material is self-extinguishing and has relatively low smoke generation, which is no more toxic than smoke generated by wood.4 With a higher limiting oxygen index (LOI) value than many other common building materials, in the absence of an external flame this system will not support combustion under normal atmospheric conditions.

Performance-wise, CPVC is durable. The material has been in production since 1959 and, unlike metallic systems, CPVC pipes will not pit, scale, or corrode—regardless of water quality. Further, the material is cost-efficient. With no torches required, CPVC systems can be installed more quickly and more easily than traditional metal systems—instead, pipe and fitting are solvent-welded quickly and firmly; they can also be mechanically joined. The system offers additional savings because it is highly energy-efficient. Further, CPVC offers advantages when it comes to product selection. Pipes and fittings up to 610 mm (24 in.) meet the needs of nearly any commercial project.

[5]

[5]

CPVC piping systems can be installed using one of two methods: chemical joining or mechanical joining.5 A one-step chemical joining process (called solvent welding) can be used on CTS CPVC systems. This system eliminates the need to use a separate primer. Installers cut the pipe, clean the pipe and fittings, apply solvent cement inside the fitting socket, assemble the joint, and verify proper installation. A two-step process (primer and solvent cement) is used in Schedule 80 systems. The science of solvent welding, both the one- and two-step processes, forms a chemical bond and ensures a properly installed fitting is the strongest part of the system.

Mechanical joining is an option for Schedule 80 CPVC systems. This consists of cutting and grooving the pipe, then connecting pipe sections with specialty fittings. Mechanical joining options are especially ideal for alterations or repairs, as they eliminate drying time and shorten system downtime. Transition fittings

for connection to other materials are also available.

Conclusion

With durability, versatility, straightforward installation, and decades of proven performance in the field, CPVC piping systems can be a suitable option for a range of commercial applications, from hospitals to office buildings to schools. By following manufacturer and code guidelines, systems can be sized to ensure optimal water pressure as well as long-term reliability of the entire system.

Notes

1 This information can be found in section E103.2.2 of the International Plumbing Code (IPC).

2 Refer to sections 604.3 and 604.5 of the IPC.

3 In CPVC systems, the dBa noise level will always be lower than that of copper. Specific sound levels vary based on pipe size and water velocity. For more information, refer to “Final Test Report on Noise Emission Comparison of FlowGuard Gold CPVC Pipe and Copper Pipe” published by NSF International, 31 May 2001. Click here[6].

4 Refer to “Acute Inhalation Toxicity of Thermal Degradation Products Using the NYS Modified Pittsburgh Protocol on Blazemaster CPVC Sprinkler Pipe” published by United States Testing Company–Biological Services Division, 8 December 1989. Click here[7].

5 While Schedule 80 pipe has thick walls and is able to withstand high pressure applications, Schedule 40 has thinner walls and is more suited for low pressure systems. Schedule 40 can only be joined with solvent welding. Schedule 80 can be joined with either solvent welding or mechanical joints.

Tom Attenweiler is a product engineer for Lubrizol, where he provides technical support to sales and marketing and helped developed the company’s engineered materials platform. He has seven years of chemical operations experience, including support of thermoplastic polyurethane resin production. A graduate of Case Western Reserve University, Attenweiler previously worked for DuPont as a chemical process engineer supporting industrial enzyme production and as a process analyzer consultant gaining exposure to a variety of chemical manufacturing processes. He can be reached via e-mail at thomas.attenweiler@lubrizol.com[8].

Don Townley is the global codes and approvals manager with Temprite Engineered Polymers of Lubrizol. He has a degree in mechanical engineering (BSME) from the University of Cincinnati. A member of the National Fire Protection Association (NFPA) Technical Committee on Residential Sprinkler Systems, Townley has more than 20 years of experience related to the design and installation of CPVC pipe and fitting systems used in fire sprinkler, industrial chemical, and potable water distribution applications. He is active in code development activities, presenting numerous code changes to both the Uniform Plumbing Code (UPC) and the International Plumbing Code (IPC). He can be reached via e-mail at donald.townley@lubrizol.com[9].

- [Image]: https://www.constructionspecifier.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/Generic-CPVC-shot.jpg

- [Image]: https://www.constructionspecifier.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/Sizing-tool-output-20171215.jpg

- [Image]: https://www.constructionspecifier.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/Ft-Lauderdale-Hotel2.jpg

- [Image]: https://www.constructionspecifier.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/9-21-2018-2-34-46-PM.jpg

- [Image]: https://www.constructionspecifier.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/9-21-2018-2-35-07-PM.jpg

- here: http://www.alwaabplastics.com/index.php/download/certification?download=21:nsf-noisetest

- here: http://www.flowguardgold.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/United-States-Testing-Pittsburgh-Protocol-12-8-89.pdf

- thomas.attenweiler@lubrizol.com: mailto:thomas.attenweiler@lubrizol.com

- donald.townley@lubrizol.com: mailto:donald.townley@lubrizol.com

Source URL: https://www.constructionspecifier.com/sizing-pipes-exploring-cpvc-as-a-material-alternative/