Smithsonian African American museum highlights heritage, art, design

by Erik Missio | October 3, 2016 2:41 pm

[1]

[1]Photos © Allan Karchmer. Photos courtesy Valspar

The Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture (NMAAHC) opened last week, taking its place on the last available spot on the National Mall in Washington, D.C.

Located on Constitution Avenue, adjacent to the National Museum of American History and the Washington Monument, the building encompasses 36,882 m2 (397,000 sf) of space across 10 levels, housing exhibit galleries, administrative areas, theatre space, and storage facilities for 33,000 pieces of artwork and historical objects.

To ensure the success of this prominent project, many partners were called together to work collaboratively during the design and construction phases, each bringing a different expertise to the project. Three U.S. architecture firms joined forces: the Freelon Group, architect of record and design team leader (and now part of global design firm Perkins+Will), Davis Brody Bond, with extensive experience in museum projects, and local D.C. firm SmithGroup. David Adjaye, lead designer of London-based Adjaye Associates, was the last to join and brought an international design element to the project. Together, they formed Freelon Adjaye Bond/SmithGroup (FABS), working cohesively to create a museum that would accurately tell the story of the African American experience.

The museum’s design features three distinct elements:

- the shape and form of the corona (the three-tiered filigree envelope wrapping around the structure);

- the porch extension that merges the building into the surrounding landscape; and

- the bronze color of the corona, which provides a distinctive look and strong presence on the National Mall.

The Corona

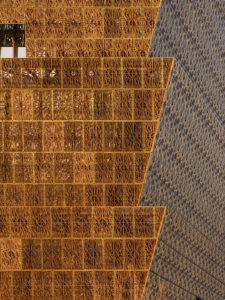

This iconic building form pays homage to the nearby Washington Monument, closely matching the nearly 17-degree angle of the capstone while using the monument’s stones as a reference for the NMAAHC panel proportion and pattern. The bronze-clad corona reaches toward the sky, serving as an expression of faith, hope, and resiliency.

“The bronze-colored plates and glass-panel façade that make up the Corona is a representation of traditional African architecture using modern materials and will visually define the museum,” said Matt Wurster from Clark Construction Group, one of the general contractors for the project. (The other two were Smoot Construction and H.J. Russell & Company.)

The Porch

An outdoor room bridging the gap between the interior and exterior of the building, this feature also unites the structure with its natural surroundings. The underside of the porch roof is tilted upward, reflecting the moving water below. This covered area creates a microclimate where breezes combine with the cooling waters to generate a place of refuge from the hot summer sun.

The Filigree

Bronze-colored panels cover the tiered exterior of the building, perforated in patterns referencing the history of African American craftsmanship. Each of the 3600 customized, bronze-colored, cast-aluminum panels reflect the design of ironwork by enslaved craftsmen in Charleston and New Orleans. The density of the pattern varies to control the amount of sunlight and transparency allowed into the interior, and the bronze color provides stark contrast to the building’s marble and limestone neighbors.

The bronze wash of the metal panels was a key component of the design. Lead project manager Zena Howard, AIA (Perkins+Will), explained the color choice was discussed over the course of many years with all parties involved in the design process. Ultimately, bronze was selected as the team determined it would remain “an enduring and permanent color that would command respect for the building and the exhibits housed inside.”

Panel discussion

Once the final color idea had been selected, the new challenge of obtaining the perfect hue began. Three custom shades (African Sunset, African Sunrise, and African Rose) and one standard shade of black were chosen for the 70 percent polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) coatings used on these massive aluminum panels, each weighing around 90 kg (200 lb) and stretching 1.2 by 1.5 m (4 x 5 ft).

“The color-matching period lasted for more than 18 months because we were looking for depth even more than just color since the panels were so intricate and unique,” said Del Stephens, president/CEO of the project’s metal panel applicators.

To achieve the exact bronze shade desired by the design team, each custom-cast panel was finished with five different coating layers, each a different color of the PVDF coating. The individual coatings needed to hold their color across every layer on the panels, as each new additional color is built off the last to create the final shade.

Extensive testing was done during the coating application process, due both to the sheer size of the panels and the intricate design already cut into each piece. The coating was applied entirely by hand, and each color layer was carefully inspected to ensure every part of the coating process was on track. The process was replicated for all 3600 panels—the team worked furiously to finish them in an identical fashion and ship them from the workstation in Portland to the D.C. project site. After a bit of back and forth, the panels and their many layers of custom colors were approved and deemed ready for installation.

“What we ended up with gave us the look of real bronze—a luminous feeling that created a dynamic and beautiful façade,” said Howard.

The first panels went up in April 2015, and the build process moved forward rapidly over the ensuing months.

[2]

[2]“The installation process went very smoothly,” said Marty Antos, project manager at Northstar Contracting, which oversaw the installation process. “This was a completely new way of installing panels, as the building is almost inside-out, with the glass on the inside and the ornamental structures, the metal panels, on the outside.”

The panels were installed within six weeks on the project site, but the assembly process took a bit longer, spanning more than one year. This was largely due to the amount of materials coming to Cleveland from across the nation, including castings from Seattle, steel frames from New Jersey, and aluminum extrusions from Missouri.

The filigree is an eye-catching adornment that both draws visitors in and sets the stage for the rest of their journey through the museum. It combines polish, artistry, creativity, and persistence—just like the art, history, and culture memorialized within the building. The museum itself is a work of art, one that stands out among the historic structures to its left and right, and will act as a physical representation of the African American history.

- [Image]: http://www.constructionspecifier.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/10/2016AK11_223.jpg

- [Image]: http://www.constructionspecifier.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/10/2016AK11_220-e1475605070386.jpg

Source URL: https://www.constructionspecifier.com/smithsonian-african-american-museum-highlights-heritage-art-design/