Smoke control: Getting it right

Pressurization systems

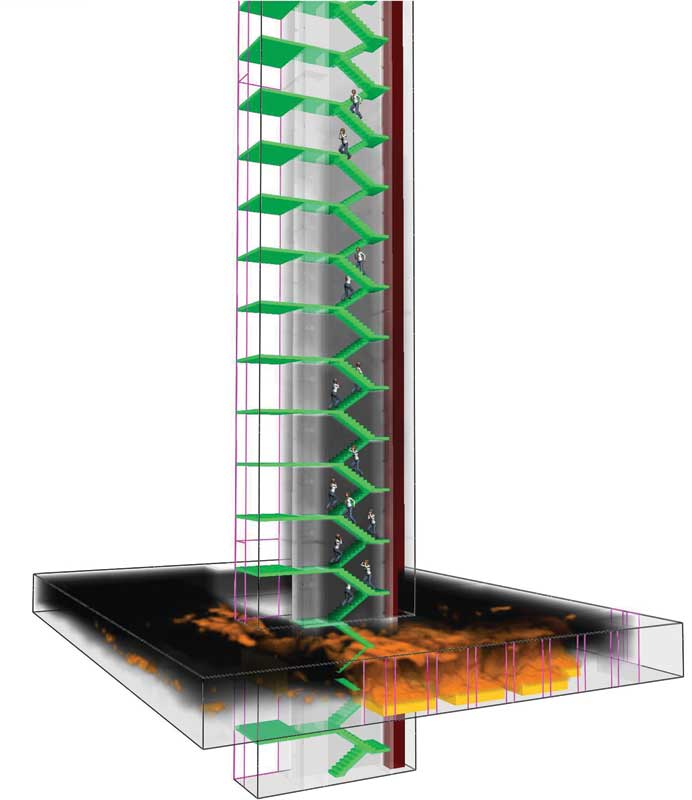

Used to keep smoke out of spaces adjacent to the zone of origin, pressurization systems rely on pressure differentials (typically 12.4 Pa [0.05 in. H2O] in sprinklered buildings) across smoke barriers to prevent the migration of smoke into other zones. This is accomplished by exhausting the zone of origin, pressurizing stairwells and exit passageways, and potentially pressurizing zones adjacent to where the fire originally started. However, the pressure differentials must not increase door-opening forces above their code-required maximums.

Fans need to be built to fit the appropriate pressure differentials. Computer models (such as CONTAM) can be used to predict pressure differences across a series of smoke control zones throughout several floors, and will account for variables such as building leakage, temperature, wind, and stack effect. Without such modeling, the complexities of a high-rise building may not be captured properly.

Even with computer modeling, actual building conditions may need to be joined with simulated conditions during construction. For example, the model requires assumptions as to how tight construction will be. Often, modelers will assume a high leakage rate, resulting in higher fan capacities. If the building construction is tighter than anticipated, this may result in door-opening forces being exceeded. One way to address this issue is to specify variable drive fans that can be set to match as-built conditions during commissioning. Without variable speed drive fans, balancing can involve adjustment of fan sheaves and undercutting of doors.

Exhaust systems

Exhaust systems are used in large, open spaces where the smoke from a fire in any portion of the location can impact the entire zone and some other areas disproportionately. For the exhaust method, the smoke control system must be adequately designed to keep the smoke layer from descending more than 1.8 m (6 ft) above the highest walking surface during egress.

Natural venting, while an allowable option, can be difficult to justify due to the effects of outside wind and the weak buoyancy of the smoke plume with smaller design fires and in cold climates.

For mechanical exhaust, algebraic equations are available in NFPA 92 to calculate design exhaust volumes to maintain the 1.8-m layer height. Early in the design process, such equations can be helpful to develop ballpark design-exhaust volumes but the equations are mostly intended for simple rectangular volumes similar to the fire tests on which they are based.

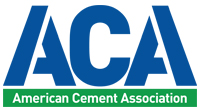

Alternatively, computational fluid dynamics (CFD) models can be used to establish the time that a space remains tenable—the available safe egress time (ASET). CFD modeling used to be less known, but NFPA 92 now explicitly recognizes it as a design methodology. CFD models allow for an accurate 3D geometry of the open space in question, dividing it into millions of cells and solving mass, energy, and momentum transport equations for and across each cell. The result is a graphical simulation of smoke flow through the space due to buoyancy, temperature, air entrainment, and its path against and around physical boundaries. The model can be used to show visibility distances through the smoke at different elevations, temperatures in various locations, and the concentration of toxic fire by-products such as carbon monoxide.

Tenability criteria—typically, visibility distance, temperature, and toxicity—must be established to determine when the model fails and the space becomes unsafe. Egress calculations or models are used to define the other side of the equation—the required safe egress time (RSET). The models simulate the evacuation time of occupants based on travel speeds, occupant characteristics, and egress locations and sizes. The basis of a performance-based smoke control design is to demonstrate occupants reach safety before the environment becomes untenable.

The most important part of CFD smoke modeling, besides accurately simulating the smoke exhaust and supply, is defining the design fire scenarios. The design fire quantifies the ‘load’ that will be placed on the smoke control system. Fire test data is available and should be used to justify the design fire. The size and characteristics of it need to reflect the potential combustible loads within the space. For example, if a small, upholstered chair is used as the design fire for a large atrium space where there may be seasonal Christmas trees or cars on display, then the smoke control system will be undersized. Since each space is unique, fire protection engineers should think critically about project-specific design fires and not simply cut and paste from previous projects. Management of the fuel loads for a space over the life of the facility to stay within the original performance-based design parameters warrants its own separate discussion.

One of the biggest architectural/mechanical challenges of a large exhaust system is the provision of supply air. NFPA 92 has a stated maximum supply airflow speed of 60 m (200 ft) per minute toward the fire based on plume deflection fire testing. This often requires very large supply grills or natural opening supply areas. The commentary to NFPA 92 recognizes CFD modeling may be used to justify higher velocities, which can help with the design. Further, supply air is typically provided at the bottom of a space to offer cool fresh air below the smoke layer for occupants exiting through the area. This can be a significant challenge when the lowest level is below grade or where the atrium is in the center of a large building with no access to the outside. Large ducts and transfer grills may not physically fit the space and will definitely impact the architecture. CFD modeling also assists with optimizing the location and type of supply for the space.

Using CFD models and egress analyses allows the design team to optimize the system (i.e. exhaust quantities) and explore the effects of changing smoke control system parameters. This provides a high degree of flexibility for increased life safety, aesthetics, and functionality. Using computer modeling to simulate the performance of the system and movement of the occupants is also a powerful visualization tool for presentation to authorities having jurisdiction (AHJs). Sound engineering needs to back up the colorful images, but a picture is worth 1000 words, as the saying goes. Thus, a video simulation can be worth 1000 pictures. Gaining approval for the smoke control approach and system design is the critical milestone at the conclusion of the design and analysis.