With respect to glass coolness, the low-emissivity (low-e) coating is one of the most important developments. Most typically placed on the #2 glass surface (i.e. the interior surface of an exterior ply of glass), it reduces the portion of heat absorbed and radiated by the inner ply of glass. Part of the transmitted shortwave infrared radiation is absorbed by the glass itself and re-radiated as heat. (Therefore, generally speaking, tinted glass should be positioned closer to the exterior because it absorbs more radiation than clear glass.)

A useful tool for visualization of the infrared glass performance involves placing different glass samples between an infrared lamp and NIR sensor. Seemingly identical glass would exhibit different solar performance. A similar comparison could be done outdoors, using the sun in lieu of an infrared lamp, and an inexpensive pyrometer instead of the NIR sensor. These elementary demonstrations enable the project team to visualize the performance described by otherwise meaningless acronyms and numbered labels.

Dealing with the heat

This author was recently approached by an architect who specified and designed a large window replacement project in his own condominium building complex in Long Island, New York. Ironically, he found the new fenestration to be unbearably cold, drafty, and covered with water condensation. Some suggest the secret of success is to know how to pass the blame—therefore, he asked how to prove the contractor provided inferior windows. This author suggested relevant field testing that could be used to verify whether the specs were met.

In this author’s experience, most field testing is performed solely to confirm inferior specifications were followed. A lot of money and aggravation would be spared if owners verified the adequacy of the architectural specifications before embarking on expensive testing. Even more could be spared if the verification happened before the construction.

As experienced by the architect in question (and his family and clients), the heat transmittance of different glass types is easily noticed. There are receptors in our skin that detect the rate of heat loss, making it simple to tell a good window from a bad window. For benchmark purposes, this is described as the U-factor; it illustrates thermal transmittance in range from 2500 to 50,000 nm (the ‘long’ infrared range).

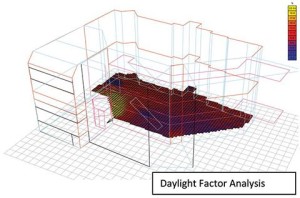

As perimeters (i.e. framing and glazing spacers) are typical bottlenecks of the U-factor, it pays to design them correctly. This author often analyzes a glazing design in the finite element analysis (FEA) computerized testing, and typically suggests simple and inexpensive improvements such as stainless steel spacer substitution, if glazing failed the virtual testing.

To put the whole thermal transmittance (i.e. U-factor) discussion into perspective, it is important in locations where the ambient temperature differences are large, like Scandinavia. In places like the United States, which mostly lies south of Europe, designers should be primarily concerned with the solar heat gain. (As a bonus, the economics are there—in most cases, the better SHGC is almost free, while the better U-factor sometimes comes with an unreasonably long return on investment [ROI].)

Another obvious factor is the draftiness (air infiltration)—its reduction can be challenging in the sliding fenestration popular in the United States, requiring core solutions such as continuous gasketing, stiff frames, and mitered framing and sash corners.

Understanding climate differences is critical—a better window in the North is not necessarily the same in the South, and may require adjustments in the mechanical system. This author was recently approached in Miami, Florida, by a mechanical engineer whose son contracted chronic respiratory illness after old projecting windows in his house were replaced with new, hurricane-proof fenestration. These assemblies are stiff and, in turn, much more airtight, causing a significant drop of the cooling load in hot and humid climates. Therefore, the air-conditioner, whose evaporator acts as a dehumidifier, works less, contributing to the inferior interior air quality (IAQ). This is why retrofitting airtight windows may require adding ventilation and dehumidification.

Data from ASHRAE

Northern Europeans, with their heavy and tight masonry buildings relying on gravity ventilation, learned it the hard way—they install window frame venting slots that automatically open when relative humidity (RH) is too high inside.

The energy conservation codes and standards generally tie the U-factor in with the glazing ratio for prescriptive compliance method. Figure 1—reproduced from American Society of Heating, Refrigerating, and Air-conditioning Engineers (ASHRAE) 90.1, Energy Standard for Buildings Except Low-rise Residential Buildings—ends at the 50 percent window-to-wall ratio (WWR) and five percent skylight-to-roof ratio. (As this is only a prescriptive path, designers can move away from these charts [e.g. using either a trade-off or energy cost budget options]. However, ‘off-the-chart’ projects are sometimes found uncomfortable by occupants, and not code-compliant when carefully examined.) The reason is simple: thermal performance of glazing is either far worse than that of opaque assemblies or prohibitively expensive (with negligible ROI).

The human body generally cannot directly and instantaneously detect solar radiation other than the VIS range, but NIR radiation is absorbed by objects (including skin) and re-radiated in the thermal range, which is felt as heat. The NIR radiation stretches from 780 to 2500 nm. This phenomenon contributes to the greenhouse effect because glass lets the NIR through, but stops the thermal range.