Solar design for windows

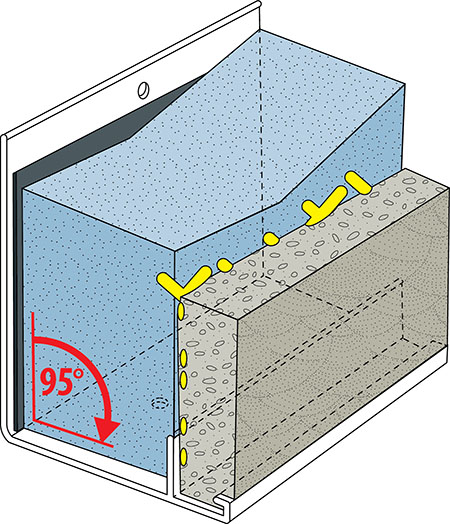

Image courtesy Karol Kazmierczak

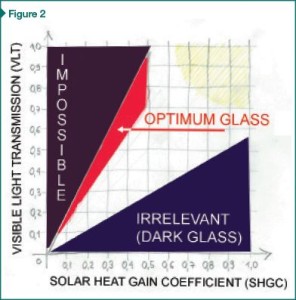

Unless one’s intention is to experiment with passive solar design, the heat gain via windows is generally undesirable, particularly in warmer climates. This author knows of a famous, ostensibly green, LEED Gold-certified, fully glazed office tower built in the South with the glass VLT specified lower than the SHGC. This means the glass coolness factor was less than 1, with approximately 50 percent window-to-floor ratio. Both SHGC and VLT are in their mid-30s. The ultimate result is the occupants are hot, and the cooling bills high.

This author is not aware of any daylighting studies performed on this tower. However, under the common-sense assumption the 15 percent VLT would be just enough (given the high window-to-floor ratio and good window access), then the SHGC could theoretically be four to five times lower should the more spectrally selective glass (at almost exactly the same initial cost) have been specified. Since the building elevations are fully glazed, the solar heat gain correlates well with the cooling energy costs. Essentially, the energy bills could probably be two times lower and occupants twice as happy.

This case illustrates the difference between the two alternative ways of approaching the solar heat gain challenge—either meeting the minimum threshold set for the cooling sizing, or the threshold set by glass production limitations with respect to natural lighting. In many cases, due to architectural over-glazing and improved glass technologies, the latter would result in a better glass, translating into a lower energy consumption and higher occupant comfort in cooling-dominated places like the United States. This is why this author believes determining the SHGC should begin with daylighting studies.

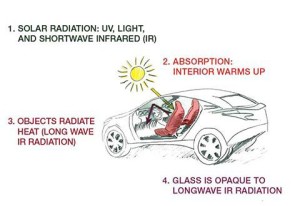

Image courtesy AGC

Sticking to vision

With glass, the most important light obstruction is dirt, and deferred maintenance has become the norm thanks to the current economy. This author has seen opportunities for doubling the light transmittance, had only the glass been regularly washed in the most severe cases. A ‘self-cleaning’ glass has been developed with a titanium hydrophilic surface. Unfortunately, this material is occasionally specified for flat skylights or under large overhangs where it serves no useful purpose because it requires sufficient rainwater flow to clean itself. The best way to ensure clean glass is to design for permanent window-washing access.

Another important way to improve visibility is to reduce reflections. To this end, anti-reflective glass can be particularly useful for showroom and retail storefronts, where it can better expose the merchandise on display. This way, one can only gain around three or four percent, but significantly improve the subjective perception of transparency. High glass reflectivity, on the other hand, may be desired in some applications where privacy is needed—a common example is a multi-family high-rise building.

A third way to increase transparency involves eliminating iron from the glass melt. Iron makes glass slightly greenish, which is more easily detectable in thicker materials. The two to four percent gain is justified in some thick, high-end applications, requiring numerous plies of laminated glass to achieve the necessary structural redundancy. Such a low-iron glass may be advisable for high-tech additions to historic landmark buildings.

The thicker the glass, the less light goes through. The necessary glass thickness can be estimated using ASTM E1300, Standard Practice for Determining Load Resistance of Glass in Buildings. The result should be the glass thickness of each glass ply. Then, using the free Windows and Optics software developed by Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory (LBNL) or similar programs, a designer can select the sufficient VLT for daylighting combined with the lowest possible SHGC before ordering samples for comparison purposes.

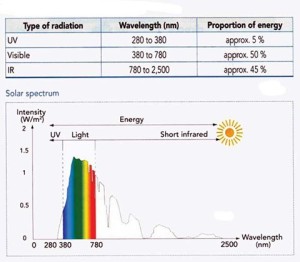

Images courtesy AGC

Window design basics

Designing the most appropriate window can begin as soon as floor plans are developed. One should pick the worst-case layout and run the DF analysis to optimize the size and VLT of the glazing and shading. Based on this VLT, and using the chart in Figure 2, a designer needs to select the feasible SHGC range. This should be verified against energy code requirements, which in the case of many large buildings is met by the energy cost budget path. Therefore, a window’s total SHGC should be coordinated with the mechanical Basis of Design (BOD), then verified with the mechanical engineer, and re-calculated to receive the nominal glass SHGC by removing projections, shading, framing, and screens. (Calculating shading offered by miscellaneous architectural assemblies can be challenging; this author advises architects to compare shading options side-by-side with energy-modeling software.)

Additional challenges come into play when assumed and calculated physical characteristics must be captured in the construction documentation for the benefit of future construction. These conditions, and others affecting engineering estimates, should be communicated with all parties to avoid misunderstandings. Ultimately, the resulting numbers illustrating the glass performance should be reflected in MasterFormat’s 08 80 00–Glazing specification section or on its referenced glass schedule.