While the owner gets to approve the construction specifications and drawings, the only changes that can be enforced on the design-builder without an appropriate contract modification are the ones consistent with the owner’s project criteria.

Although the level of detail and ‘prescriptiveness’ of design build construction specifications may vary from the ones prepared for DBB, DNB, CMa, and CMAR, they are organized in accordance with CSI MasterFormat and SectionFormat just like more traditional specifications.

The alternative standard forms of owner–design-builder prime contracts in widespread use in the United States take different approaches to the term used for specifications. For example:

- DBIA uses the term “Construction Documents” (encompassing both specifications and drawings);

- AIA uses “Instruments of Service” (includes specifications, drawings, and other documents); and

- EJCDC uses multiple terms, such as “Construction Specifications,” “Record Specifications,” “Construction Drawings,” and “Record Drawings.”

The drafter of construction specifications for a design-build project should carefully coordinate the construction specs with the associated prime contract, including appropriately using defined terms.

As described throughout this article, design-build construction specifications are different from the ones for DBB, DNB, CMa, and CMAR projects. However, most master specifications, whether maintained by a consulting engineering, architecture firm, or commercial third-party master guide specifications, are written for DBB projects. The time and effort needed to tailor DBB source specifications for a design-build project can be substantial and is often greater than the effort to merely tailor existing DBB specifications for a given DBB project. Design professionals should factor into their budgets and schedules the time and effort needed to properly adapt DBB specifications for design-build. Due to the many variables affecting construction of work results in a design-build project, there may never be a master guide specification prepared expressly for design-build projects.

Are construction specifications a part of the contract documents?

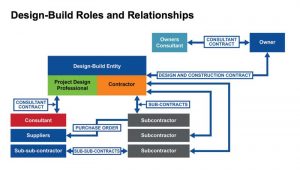

Under the prime contract, the design-builder is responsible for designing, constructing, and delivering a completed project consistent with the owner’s project criteria and other prime contract documents. As part of the work, the design builder prepares construction drawings and specifications.

How the design-build construction specifications should be written depends, in part, on whether they will become part of the prime contract documents. Not all standard design-build prime contracts in widespread use in the United States treat this matter equally.

DBIA 525–2010, Standard Form of Agreement between Owner and Design-Builder–Lump Sum, indicates at Section 2.1 what constitutes contract documents, including “Construction Documents prepared and approved in accordance with Section 2.4 of the General Conditions,” thus expressly making the specification and drawings part of the prime contract. Section 2.4.2 of DBIA 535–2010, Standard Form of General Conditions of Contract between Owner and Design-Builder, also says, that “Design-builder shall proceed with construction in accordance with the approved Construction Documents.”

AIA A141–2014, Standard Form of Agreement between Owner and Design-Builder, uses the term “Design-Build Documents,” to indicate what comprises “the contract,” as follows:

- 1.4.1 … The Design-Build Documents consist of this Agreement … and its attached Exhibits (hereinafter, the “Agreement”); other documents listed in this Agreement; and Modifications issued after execution of this Agreement.

Also, Article 16, “Scope of the Agreement,” of AIA A141–2014 is a more detailed listing of what constitutes “the Agreement.” It includes a space for tailoring by the drafter of the project agreement, but the default language of Article 16, and elsewhere in AIA A141–2014, does not indicate specifications or other instruments of service are part of the design-build documents (prime contract). Nowhere does the model language of AIA A141–2014 require the design-builder to construct the project in accordance with the instruments of service. This appears to allow the design-builder considerable latitude in how it implements the project, as long as the completed project is consistent with the owner’s criteria, which are set forth in Section 1.1 of AIA A141–2014.

EJCDC D-520–2016, Agreement between Owner and Design-Builder on the Basis of a Stipulated Price, establishes what constitutes contract documents in Paragraph 7.01. It does not include construction specifications or drawings. However, Paragraph 7.01.A.11.c incorporates “Record Drawings and Record Specifications” as contract documents.

Also, EJCDC D-700–2016, Standard General Conditions of the Contract between Owner and Design-Builder, Paragraph 7.02.A, requires:

Design-Builder shall perform and furnish the Construction pursuant to the Contract Documents, the Construction Drawings, and the Construction Specifications, as duly modified.

However, under EJCDC’s documents, the design-builder has the right to modify its own construction drawings and specifications, as long as they remain in accordance with the contract documents, including the owner-prepared conceptual documents.

| ORGANIZATIONAL FORMATS FOR BRIDGING DOCUMENTS |

| Owner’s project criteria, also known as “bridging documents,” “conceptual documents,” or “owner’s criteria,” sometimes do not employ recognized organizational formats. Conversely, many sets of owner’s project criteria documents, especially for vertical construction design-build projects, are organized in accordance with CSI’s UniFormat, which structures construction information and requirements by ‘facility elements.’ In contrast, CSI’s well-known MasterFormat is used for organizing construction specifications and is based around detailed ‘work results.’

Since they are often generalized, owner’s project criteria for design-build projects should not be organized using MasterFormat unless the owner will allow the design-builder very little latitude in developing the design. This may, in turn, reduce competition among prospective design-builders and result in higher costs to the owner. In addition to UniFormat, CSI also publishes PPDFormat, which presents a recommended approach for preparing ‘preliminary project descriptions.’ Although intended largely for design-bid-build (DBB), design-negotiate-build (DNB), construction manager as advisor (CMa), and construction manager-at-risk (CMAR) projects, the approaches set forth in PPDFormat may be useful in establishing the level of detail set forth in owner’s project criteria for design-build projects. Chapter 12 of CSI’s Construction Specifications Practice Guide (CSPG) presents guidance on performance specifying, useful in preparing both owner’s project criteria and performance specifications for construction. Also, Section 1.14.3 of CSPG directly addresses owner’s project criteria and other documents developed in design-build project delivery. |