Specifications for design-build projects

by sadia_badhon | June 11, 2021 9:20 pm

[1]SPECIFICATIONS

[1]SPECIFICATIONS

by Kevin O’Beirne, PE, FCSI, CCS, CCCA

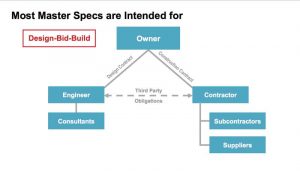

Specifications originally intended for design bid-build (DBB) projects require significant revisions to be suitable for design-build or integrated project delivery (IPD).

A substantial challenge faced by professionals preparing construction specifications for design build projects is most master specifications were developed for traditional DBB or its ‘close relation,’ design-negotiate-build (DNB). Often, DBB specifications can be adapted with reasonable effort and cost for use on construction manager as advisor (CMa) and construction manager-at-risk (CMAR) projects. Greater challenges arise when adapting DBB source documents for design-build.

DBB and its ‘relatives’ are longstanding methods of project delivery with clearly defined roles and responsibilities, and, therefore, drafting construction specifications for such projects is reasonably straightforward.

In DBB, DNB, CMa, and CMAR, the owner directly hires a third-party design professional to prepare the construction documents—over which the owner has full control throughout the design stage—prior to the contractor preparing its final pricing and constructing the facility. In each of these delivery methods, the design professional typically prepares very prescriptive, detailed specifications and drawings. The contractor is required to build the project in complete compliance with the drawings, specifications, and other contract documents (Figure 1).

Thus, whether it is the master specifications of an architecture or engineering firm or project owner, SpecsIntact (an automated master specifications system used by several government agencies), or commercial master guide specifications, chances are the available source documents were written for DBB projects. There are several factors to consider when adapting DBB specifications for use on a design-build project.

[2]

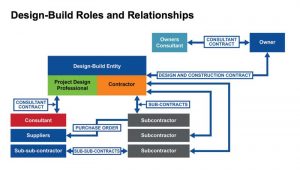

[2]Design-build contractual relationships

In design-build, the owner typically enters into a single prime contract with an entity called the design-builder that is responsible for both designing and building the project. The design builder may be a single organization with inhouse design and construction expertise and licensure or, more commonly, it is either a contractor or design professional teaming with one or more partners via subcontracts (Figure 2).

An optional entity in design-build is an ‘owner’s consultant’ (not the project’s design professional) that may be retained to help the owner in selecting the design-builder and, perhaps, in fulfilling its duties under the owner–design-builder prime contract.

According to a June 2018 report titled “Design-Build Utilization Combined Market Study,” prepared for the Design-Build Institute of America (DBIA), up to 44 percent of the United States’ non-residential construction market in 2018-2021 is predicted to employ design-build project delivery, especially in manufacturing, highway/streets, and education. The proportion of spending using design-build may vary with the type of construction and the status of enabling legislation in each jurisdiction but, regardless, design-build will represent a substantial portion of the modern design and construction market.

Prime contract between the owner and design-builder

The following standard design-build contract forms are widely used in the United States:

- DBIA – DBIA’s documents are very common in design-build project delivery. At the time of this writing, most of DBIA’s 26 standard contract documents were published in 2010 and 2012. DBIA documents are used in both vertical construction and horizontal (infrastructure) work.

- American Institute of Architects (AIA) – AIA has approximately 11 contract documents specific to design-build, most recently published in 2014- 2015. AIA’s design-build documents are used largely on vertical construction projects.

- Engineers Joint Contract Documents Committee (EJCDC) – A joint venture of the American Society of Civil Engineers (ASCE), American Council of Engineering Companies (ACEC), and the National Society of Professional Engineers (NSPE), EJCDC has a family of 16 design-build documents in its D-series, most recently published in 2016. These are used largely for horizontal projects.

- ConsensusDocs – ConsensusDocs is a coalition of approximately 40 industry organizations, led by the Associated General Contractors of America (AGCA). ConsenusDocs’ 400-series set covers design-build delivery and includes 22 documents, most recently updated in 2017, and primarily used on private projects.

The document used for a given design-build project may depend on the entity selecting or recommending the form of contract. In the author’s experience, owners seem to prefer DBIA contracts, contractors are more inclined toward DBIA or ConsensusDocs, engineers recommend EJCDC, and architects prefer AIA or DBIA. These are, of course, extremely broad generalizations. The form of the prime contract documents may have a strong influence on the associated construction specifications and are established before the latter are prepared.

The entity selecting the form of the design-build prime contract should be familiar with the risk allocations and responsibilities set forth in the owner–design-builder prime contract, and should consider them in conjunction with the owner’s project goals.

In addition to the owner–design-builder agreement, general conditions, and supplementary conditions, an essential element of the prime contract is the document(s) DBIA calls “owner’s project criteria.” EJCDC refers to them as “conceptual documents” and the AIA’s corresponding term is “owner’s criteria.” In the industry, the informal term “bridging documents” is often used.

[3]

[3]Owner’s project criteria

Documents comprising the owner’s project criteria are separate from the design-builder’s construction specifications and drawings. As the name implies, the owner’s project criteria set forth the owner’s requirements for scope, extent, performance, and quality for the completed project. Conceptual requirements set forth in the owner’s project criteria documents typically do not contain traditional construction specifications, but owners desiring a high degree of control over the project’s outcome may include them in the owner’s project criteria.

Instead of being prepared by the design-builder’s design professional(s), the owner’s project criteria are drafted by either the owner’s employees or a third-party consultant. Owner’s project criteria are typically not sealed and signed because they are not intended as design or construction documents.

When retained, an owner’s consultant is typically charged with helping the owner draft the design-build prime contract and request for proposals (RFP), preparing the owner’s project criteria, and assisting the owner in evaluating proposals and selecting the design-builder. On some design-build projects, owner’s consultants may have additional responsibilities.

The owner’s project criteria may be as brief as one page or as exhaustive as 400 or more pages of text and dozens of conceptual drawings, depending on the extent of design freedom the owner grants the design-builder. The completeness of the project’s overall definition in the owner’s project criteria varies widely, although 10 to 20 percent may be common. However, in ‘progressive’ design-builds, the project definition set forth in the owner’s project criteria is typically one to five percent complete (progressive design-build is a form of design-build in which the project’s definition is quite low at the time the parties enter into the prime contract, allowing the owner and design-builder to collaborate in defining the project’s scope and the quality requirements without preconceived constraints. In progressive design-builds, the design-builder is typically retained based on qualifications, rather than qualifications and a price proposal. The EJCDC and the DBIA publish progressive design-build agreement forms). In other cases, the owner’s project criteria may be quite voluminous and advance the design to 50 percent or more. Axiomatically, the greater the design definition at the time the prime contract is signed, the fewer and smaller are the benefits to the owner of using design-build as a project delivery method.

Whether the owner’s project criteria documents keep the design-builder on a short or long leash depends on the extent to which the owner trusts its design-builder and desires to encourage design innovation. Obviously, the level of project definition and detail in the owner’s project criteria strongly affects preparation of the associated construction specifications. How much the owner trusts the design-builder will likely hinge on whether the owner can simply choose a design builder (as in private work) or the selection will be through an open process of competitive proposals (typical for public work) as well as the owner’s prior experience with design build. Owners less-experienced with design-build may prefer to retain greater control over the design and, hence, often issue more detailed and prescriptive owner’s project criteria.

Regardless, in preparing the owner’s project criteria, care and professional judgment must be exercised, together with due consideration of the owner’s project goals.

Owner’s project criteria documents commonly employ ‘performance specifying’ (i.e. setting forth performance requirements for the completed project) and indicate the options or features expressly required by the owner, as opposed to detailed, descriptive specifying or proprietary specifying (i.e. indicating manufacturers and products by name).

Relying on performance specifying may also help shield the owner from design-builders’ claims asserting the Spearin Doctrine. Under a 1918 U.S. Supreme Court decision (United States vs. Spearin, 248 U.S. 132), a contractor is not responsible for defects in owner-issued construction documents employing prescriptive requirements. However, under a later case (Fru-Con Constr. Corp. vs. United States, 42 Fed. Ct. 94, 1998), it was determined performance specifications are not actionable as the Spearin Doctrine claims.

At least two entities publish performance-based master guide specifications, either suitable for or expressly intended for use as owner’s project criteria for certain types of design-build projects, including the U.S. Naval Facilities Engineering Command’s (NAVFAC’s) Design-build Master Request for Proposals templates. This includes design-builder solicitation documents, design-build prime contract documents, as well as performance specifications templates for 10 different types of common U.S. Navy shore-based facilities. The second system is a commercially available family of master guide performance specifications for vertical construction.

Regardless of their source documents, owner’s project criteria are the requirements the completed project must achieve and against which the design-builder’s work will be judged. They are the ‘rules’ the design-builder’s construction specifications and drawings must satisfy.

Design-build construction specifications

Design-build construction specifications are different from the owner’s project criteria. Construction specifications and drawings are prepared, sealed, and signed by the project’s design professional(s), and are the basis for constructing the project.

At the outset of the construction stage, all projects, regardless of delivery method, must have adequate drawings and specifications. The difference between design-build and more traditional types of project delivery (DBB, DNB, CMa) is that, in the former, the construction specifications and drawings are prepared after the owner has retained the builder, and are drafted by either the design-builder itself or by its consultant (i.e. the project’s design professional). All standard forms of owner–design-builder prime contract in widespread use in the United States require the design builder to submit its construction specifications and drawings to the owner for approval before commencing construction.

[4]

[4]While the owner gets to approve the construction specifications and drawings, the only changes that can be enforced on the design-builder without an appropriate contract modification are the ones consistent with the owner’s project criteria.

Although the level of detail and ‘prescriptiveness’ of design build construction specifications may vary from the ones prepared for DBB, DNB, CMa, and CMAR, they are organized in accordance with CSI MasterFormat and SectionFormat just like more traditional specifications.

The alternative standard forms of owner–design-builder prime contracts in widespread use in the United States take different approaches to the term used for specifications. For example:

- DBIA uses the term “Construction Documents” (encompassing both specifications and drawings);

- AIA uses “Instruments of Service” (includes specifications, drawings, and other documents); and

- EJCDC uses multiple terms, such as “Construction Specifications,” “Record Specifications,” “Construction Drawings,” and “Record Drawings.”

The drafter of construction specifications for a design-build project should carefully coordinate the construction specs with the associated prime contract, including appropriately using defined terms.

As described throughout this article, design-build construction specifications are different from the ones for DBB, DNB, CMa, and CMAR projects. However, most master specifications, whether maintained by a consulting engineering, architecture firm, or commercial third-party master guide specifications, are written for DBB projects. The time and effort needed to tailor DBB source specifications for a design-build project can be substantial and is often greater than the effort to merely tailor existing DBB specifications for a given DBB project. Design professionals should factor into their budgets and schedules the time and effort needed to properly adapt DBB specifications for design-build. Due to the many variables affecting construction of work results in a design-build project, there may never be a master guide specification prepared expressly for design-build projects.

Are construction specifications a part of the contract documents?

Under the prime contract, the design-builder is responsible for designing, constructing, and delivering a completed project consistent with the owner’s project criteria and other prime contract documents. As part of the work, the design builder prepares construction drawings and specifications.

How the design-build construction specifications should be written depends, in part, on whether they will become part of the prime contract documents. Not all standard design-build prime contracts in widespread use in the United States treat this matter equally.

DBIA 525–2010, Standard Form of Agreement between Owner and Design-Builder–Lump Sum, indicates at Section 2.1 what constitutes contract documents, including “Construction Documents prepared and approved in accordance with Section 2.4 of the General Conditions,” thus expressly making the specification and drawings part of the prime contract. Section 2.4.2 of DBIA 535–2010, Standard Form of General Conditions of Contract between Owner and Design-Builder, also says, that “Design-builder shall proceed with construction in accordance with the approved Construction Documents.”

AIA A141–2014, Standard Form of Agreement between Owner and Design-Builder, uses the term “Design-Build Documents,” to indicate what comprises “the contract,” as follows:

- 1.4.1 … The Design-Build Documents consist of this Agreement … and its attached Exhibits (hereinafter, the “Agreement”); other documents listed in this Agreement; and Modifications issued after execution of this Agreement.

Also, Article 16, “Scope of the Agreement,” of AIA A141–2014 is a more detailed listing of what constitutes “the Agreement.” It includes a space for tailoring by the drafter of the project agreement, but the default language of Article 16, and elsewhere in AIA A141–2014, does not indicate specifications or other instruments of service are part of the design-build documents (prime contract). Nowhere does the model language of AIA A141–2014 require the design-builder to construct the project in accordance with the instruments of service. This appears to allow the design-builder considerable latitude in how it implements the project, as long as the completed project is consistent with the owner’s criteria, which are set forth in Section 1.1 of AIA A141–2014.

EJCDC D-520–2016, Agreement between Owner and Design-Builder on the Basis of a Stipulated Price, establishes what constitutes contract documents in Paragraph 7.01. It does not include construction specifications or drawings. However, Paragraph 7.01.A.11.c incorporates “Record Drawings and Record Specifications” as contract documents.

Also, EJCDC D-700–2016, Standard General Conditions of the Contract between Owner and Design-Builder, Paragraph 7.02.A, requires:

Design-Builder shall perform and furnish the Construction pursuant to the Contract Documents, the Construction Drawings, and the Construction Specifications, as duly modified.

However, under EJCDC’s documents, the design-builder has the right to modify its own construction drawings and specifications, as long as they remain in accordance with the contract documents, including the owner-prepared conceptual documents.

| ORGANIZATIONAL FORMATS FOR BRIDGING DOCUMENTS |

| Owner’s project criteria, also known as “bridging documents,” “conceptual documents,” or “owner’s criteria,” sometimes do not employ recognized organizational formats. Conversely, many sets of owner’s project criteria documents, especially for vertical construction design-build projects, are organized in accordance with CSI’s UniFormat, which structures construction information and requirements by ‘facility elements.’ In contrast, CSI’s well-known MasterFormat is used for organizing construction specifications and is based around detailed ‘work results.’

Since they are often generalized, owner’s project criteria for design-build projects should not be organized using MasterFormat unless the owner will allow the design-builder very little latitude in developing the design. This may, in turn, reduce competition among prospective design-builders and result in higher costs to the owner. In addition to UniFormat, CSI also publishes PPDFormat, which presents a recommended approach for preparing ‘preliminary project descriptions.’ Although intended largely for design-bid-build (DBB), design-negotiate-build (DNB), construction manager as advisor (CMa), and construction manager-at-risk (CMAR) projects, the approaches set forth in PPDFormat may be useful in establishing the level of detail set forth in owner’s project criteria for design-build projects. Chapter 12 of CSI’s Construction Specifications Practice Guide (CSPG) presents guidance on performance specifying, useful in preparing both owner’s project criteria and performance specifications for construction. Also, Section 1.14.3 of CSPG directly addresses owner’s project criteria and other documents developed in design-build project delivery. |

| TERMINOLOGY |

| Construction specifications should be drafted to use defined terms and terminology that is consistent with their associated contract(s). This will increase the potential for more consistent interpretations of contractual requirements, as intended by the documents’ drafter.

When design-build construction specifications are developed from the traditional design-bid-build (DBB) specifications, commonly used defined terms in the source specifications may need modification. For example, “Contractor” will likely need to be changed to “Design-builder” or “Subcontractor.” The role of the design professional in design-build is different from traditional DBB, design-negotiate-build (DNB), construction manager as advisor (CMa), or construction manager-at-risk (CMAR), and responsibilities allocated to the design professional in DBB specifications may need to be modified for design-build. In DBB, the owner-hired design professional is the owner’s representative and ‘watchdog,’ visiting the site and reviewing shop drawings to help ensure compliance with the contract. In contrast, in design-build, the design professional works for the design-builder and is responsible only to its client and the obligations of its professional license. In design-build, the design professional neither represents the owner nor serves as the owner’s onsite watchdog. In design-build, the design-builder’s project design professional(s) are responsible for the design, but not for observing the construction and ensuring it is in accordance with the owner’s project criteria. Therefore, in preparing design-build construction specifications from DBB source documents, each instance of the terms “Engineer,” “Architect,” or “Consultant” (as applicable) needs to be carefully considered and possibly revised, depending on the project and how the design-builder will implement the construction plan. This is not to suggest the design professional abdicates its responsibility for the design once construction starts. In some standard design-build prime contracts, the owner has an explicit right to rely on the design-builder’s project design professional(s) complying with the obligations of their professional license. Finding the appropriate balance between allowing the design-builder and its construction subcontractors appropriate leeway in implementing the construction, while complying with the letter and intent of professional licensure obligations, can be challenging in design-build, where such responsibilities tend to become blurred compared with those in DBB, DNB, CMa, and CMAR. Other defined terms or terminology common in DBB source specifications may also need modification. For example, many standard contract documents and specifications for DBB, DNB, CMa, and CMAR include the defined term “Work,” referring to the physical construction and related services to be performed by the contractor. However, in design-build, the term “Work” is often defined as including both the construction and project design professional services. The extent to which the design-builder warrants to the owner “the Work,” as opposed to “the Construction” (a term defined in the Engineers Joint Contract Documents Committee [EJCDC] D-700–2016, “Standard General Conditions of the Contract between Owner and Design-Builder.”) is relevant to this matter. Even the commonly used term “Work” needs to be carefully evaluated in the source documents used for design-build construction specifications. Similar cautions may also apply to other defined terms. |

[5]

[5]EJCDC’s rationale for excluding construction specifications and drawings from the contract documents is to allow the design-builder appropriate latitude with how it implements the construction. EJCDC’s rationale for including “Record Drawings and Record Specifications” as contract documents is for the owner’s enforcement of the contractual correction period and warranty obligations (this article’s author was intimately involved in drafting EJCDC’s 2016 D-series documents).

In addition to the above, many non-standard design-build prime contracts that were reviewed by this article’s author include construction specifications and drawings as part of the prime contract documents. Practices are inconsistent as to whether construction specifications and drawings are part of the owner–design-builder prime contract and thus enforceable by the owner.

When the construction specifications are part of the prime contract, it is essential for them to be closely coordinated with the latter’s provisions. For example, construction specifications should consistently use the same terms defined in the prime contract’s general conditions or elsewhere in the contract.

It may occur to some drafters of design-build construction specifications that are to be part of the prime contract that errors or omissions in such coordination may, possibly, work to the benefit of the design-builder and its subcontractors, such as the project’s design professional. However, failing to properly coordinate the specifications with the prime contract could, possibly, breach the standard of care and, if done knowingly, be fraudulent. Therefore, when the specifications are contract documents, it is important for design professionals to properly coordinate construction specifications with the owner–design-builder contract.

A related matter is whether the construction specifications and drawings are part of the construction subcontracts awarded by the design-builder.

Paragraph 13.01.A.3 of EJCDC D-523–2016, Construction Subcontract for Design-Build Project, includes this in the construction subcontract:

Exhibit A—Scope of Subcontract Work. [Typically include from the Design-Build Contract: Specifications, Division 01 (attach to exhibit); other expressly identified Specification sections (attach to exhibit); Drawings (incorporate by reference if not attached); delegated design requirements, if any.]

Section 9.1.3, “the Specifications,” in Article 9, “Enumeration of the Contract Documents,” of AIA A142–2014, Standard Form of Agreement between Design-Builder and Contractor, includes space to indicate the relevant specifications.

Section 1.2.1 of DBIA 555–2010, Standard Form of Agreement between Design-Builder and General Contractor— Lump Sum, defines construction documents as including drawings and specifications. Section 1.3 lists the contract documents, under which Section 1.3.1.3 includes the construction documents.

Thus, the standard construction subcontract forms for design-build uniformly and expressly include construction specifications and drawings as part of the subcontract.

Who is the builder?

It is important to understand which entity will be the construction specifications’ intended recipient and user before drafting the documents.

The builder could be either the design-builder’s employees, a general contractor (GC) hired by the design-builder, construction trade subcontractors, or a combination of these. Writing for the intended recipient of each specifications section is essential.

Where the design-builder’s employees will build all or part of the project, it is likely that the design-builder would prefer broad specifications with some leeway in their implementation In this situation, performance specifying is likely to be desirable, although they must be consistent with the owner’s project criteria.

When the builder will be a GC (i.e. construction subcontractor) hired by the design-builder (common when the design-builder is a developer or design consultant) or individual trade subcontractors, it is likely the design-builder would prefer the construction specifications to be the same as those used for DBB, DNB, CMa, or CMAR projects: prescriptive, clear, unambiguous, and with little leeway. Such specifications provide greater certainty of the outcome of the construction.

When the construction will be by a combination of the design-builder’s employees and one or more construction subcontractors, it is advisable for the design-builder to identify the construction elements it will build with its own employees and inform the project design professional(s) accordingly. Doing so will help prepare the necessary sections using performance specifying or with other appropriate leeway, while specifications for work that will be subcontracted can be prepared in a more prescriptive manner.

A consideration in preparing design-build construction specifications and drawings is how the design professional’s documents square with the builders’ construction means and methods. In DBB, DNB, and CMa, the project’s design professional rarely considers construction means and methods in detail during the design stage. In design-build, however, the designer and builder are on the same team and, thus, construction means and methods are important considerations during design. Design-build is, after all, a more-collaborative approach than DBB, DNB, and CMa, which means the designer must work closely with the builder(s) during the design stage and tailor the specifications and drawings accordingly.

Another consideration is whether the construction subcontract compensation method will be stipulated price or cost-plus-a-fee. Where the compensation method is cost- plus-a-fee, the design-builder may desire the construction specifications for subcontractors allow a certain degree of latitude to encourage the builder(s) to complete their work for amounts less than their associated guaranteed maximum price, under the premise innovation encourages cost savings.

Conclusion

In preparing suitable design-build construction specifications, the design professional needs to understand not only the design intent (as is always the case, regardless of project delivery method), but also how the design-builder intends to implement the construction, including which work will be subcontracted, subcontract compensation method(s), and planned construction means and methods, and appreciate the need for the construction specifications to be well-coordinated with the applicable contracts. Since there are many approaches to design-build project delivery, there are numerous variations and nuances that affect the preparation of construction specifications for each project.

Appropriate specifying methods need to be understood and employed, in both the development of owner’s project criteria/bridging documents and design-build construction specifications. The organizational approach, level of detail, and language/style employed in these documents will vary with the owner, design-builder, and project type (the author acknowledges the advice and comments on drafts of this article from Gerard Cavaluzzi, Esq., vice-president and general counsel at Kennedy/Jenks Consultants, Inc.).

Kevin O’Beirne, PE, FCSI, CCS, CCCA, is the national manager of engineering specifications at HDR, a global engineering and architecture firm. He has more than 30 years of experience designing and constructing water and wastewater infrastructure. O’Beirne serves on various CSI national committees and is an ACEC delegate to the Engineers Joint Contract Documents Committee (EJCDC). He can be reached via e-mail at kevin.obeirne@HDRinc.com[6].

- [Image]: https://www.constructionspecifier.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/OBeirne-Kevin-2018-11-17.jpg

- [Image]: https://www.constructionspecifier.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/ODOT_MLK-I-71-1051.jpg

- [Image]: https://www.constructionspecifier.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/FIgure-1-Spec.jpg

- [Image]: https://www.constructionspecifier.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/FIgure-2-Spec.jpg

- [Image]: https://www.constructionspecifier.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/ODOT_MLK-I-71-1071.jpg

- kevin.obeirne@HDRinc.com: mailto:kevin.obeirne@HDRinc.com

Source URL: https://www.constructionspecifier.com/specifications-for-design-build-projects-2/