Stone attachments: The challenges with epoxy-set anchors

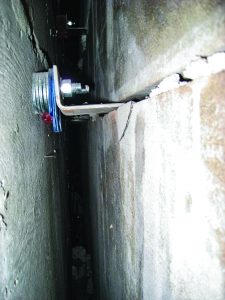

In response to reports of mortar bond separation and outward displacement of isolated cornice units, an investigation was performed in 2008 to identify the potential cause(s) of distress. A visual survey of all cornice units indicated cracked and/or bond separation of mortar existed at approximately 30 percent of all mortar joints between adjacent cornice units. In a few instances, mortar had even become dislodged between the top horizontal surface of the limestone cornice and the limestone ashlar directly above it (Figure 9). Inspection openings were made by removing the limestone cap at the top of the exterior wall, cutting through a membrane flashing, and examining the back face of the cornice. The inspection opening allowed examination of two cornice units and a total of four strap anchor connections. At the inspection opening, spalls were observed to the back face of the limestone cornice at each strap anchor connection (Figure 10). In some cases, epoxy remnants remained bonded to the limestone face of the kerf slot at limestone spalls (Figure 11), and in other instances, remaining epoxy remnants bonded to the strap anchor (Figure 12). Analysis of the strap anchor connection revealed the limestone at the kerf has sufficient strength to resist design loads.

It is unknown if the anchor voids were specified to be filled with mortar or sealant. However, the cornice anchors were likely set with epoxy to increase the installation rate of the limestone cornice units.

Conclusion

In its fully cured state, epoxy is typically a hard material with a modulus of elasticity comparable to that of limestone. Therefore, when the temperature is elevated relative to when the epoxy cured, thermal expansion of epoxy occurs that is significantly greater than of the adjacent limestone. Where the epoxy is confined by the limestone within dowel holes or kerfs, significant expansive forces can develop that, to an extent, are resisted by the adjacent limestone. With an increase in temperature and resulting epoxy expansion, depending on the geometry of assembly, most importantly edge distance and void volume, the limestone is no longer able to accommodate the developing forces. The expansive forces can be significantly high, resulting in shear and/or tensile stresses in the limestone exceeding the ultimate strength of the material. The cracking and spalls observed in the case studies presented are consistent with the development of high stresses at dowel and kerf connections the author has observed on other buildings and during controlled laboratory testing.

The confinement of epoxy within anchored limestone assemblies can lead to cracking in different types of assemblies. Additional analytical and laboratory studies are needed to further evaluate the mechanism(s) causing cracking for epoxy-set anchors in limestone and other materials.

Consistent with the Indiana Limestone Institute (ILI) recommendations, anchor voids in limestone should be filled with mortar or sealant, or other non-expansive, stable material. Filling anchor voids in dowel holes or kerfs with epoxy should only be considered after careful study of material properties and anchorage geometries proposed for use as part of a limestone attachment assembly.