Taking a new approach to concrete

by Katie Daniel | March 1, 2016 3:38 pm

by Jay H. Paul, SE, FACI, and Gene R. Stevens, PE, SE, M.ASCE

In 2006, the Strategic Development Council of the ACI Foundation (established by the American Concrete Institute) recognized the need to set minimum requirements for strength, serviceability, and durability for existing structures. They envisioned standards much like those provided for new construction by the International Building Code (IBC) and ACI 318, Building Code Requirements for Structural Concrete.

Thus, the Strategic Development Council developed the Vision 2020 plan for the concrete repair, protection, and strengthening industry. A key part of its mission was to create a repair and rehabilitation code that would improve the efficiency, safety, and quality of concrete repair. As more concrete professionals become involved in the field of repair and rehabilitation, a common code ensures consistency of practices and ultimately raises the level of structural performance and public safety.

ACI Committee 562 (Evaluation, Repair, and Rehabilitation of Concrete Buildings), spent seven years developing a code to unify industry practices. The 31-member team of engineers, contractors, and manufacturers—including many members of the International Concrete Repair Institute (ICRI)—produced the Code Requirements for Evaluation, Repair, and Rehabilitation of Concrete Buildings (i.e. ACI 562) in 2013.

The code represents a major milestone in the concrete repair industry—not only is it the first material-specific set of requirements for the repair of reinforced concrete, but it also serves as ACI’s first performance-based code. This new approach is changing concrete repair and rehabilitation in several important ways.

1. Specifiers have more flexibility to use their professional judgment.

ACI 562-13 is carefully structured to give engineers and architects significant latitude in approaching concrete repair. While drafting the code, the committee members concluded it would be highly impractical to apply any prescriptive requirements due to the wide range of existing concrete buildings built using different building codes and materials, and exhibiting various repair and rehabilitation issues.

Instead, they developed a performance-based code that provides a minimum baseline of requirements rather than dictating specific formulas that must always be applied. Designers can select the best options for each project, taking into account variables such as extent of deterioration or damage, materials used, age of the structure, environmental conditions, and durability requirements.

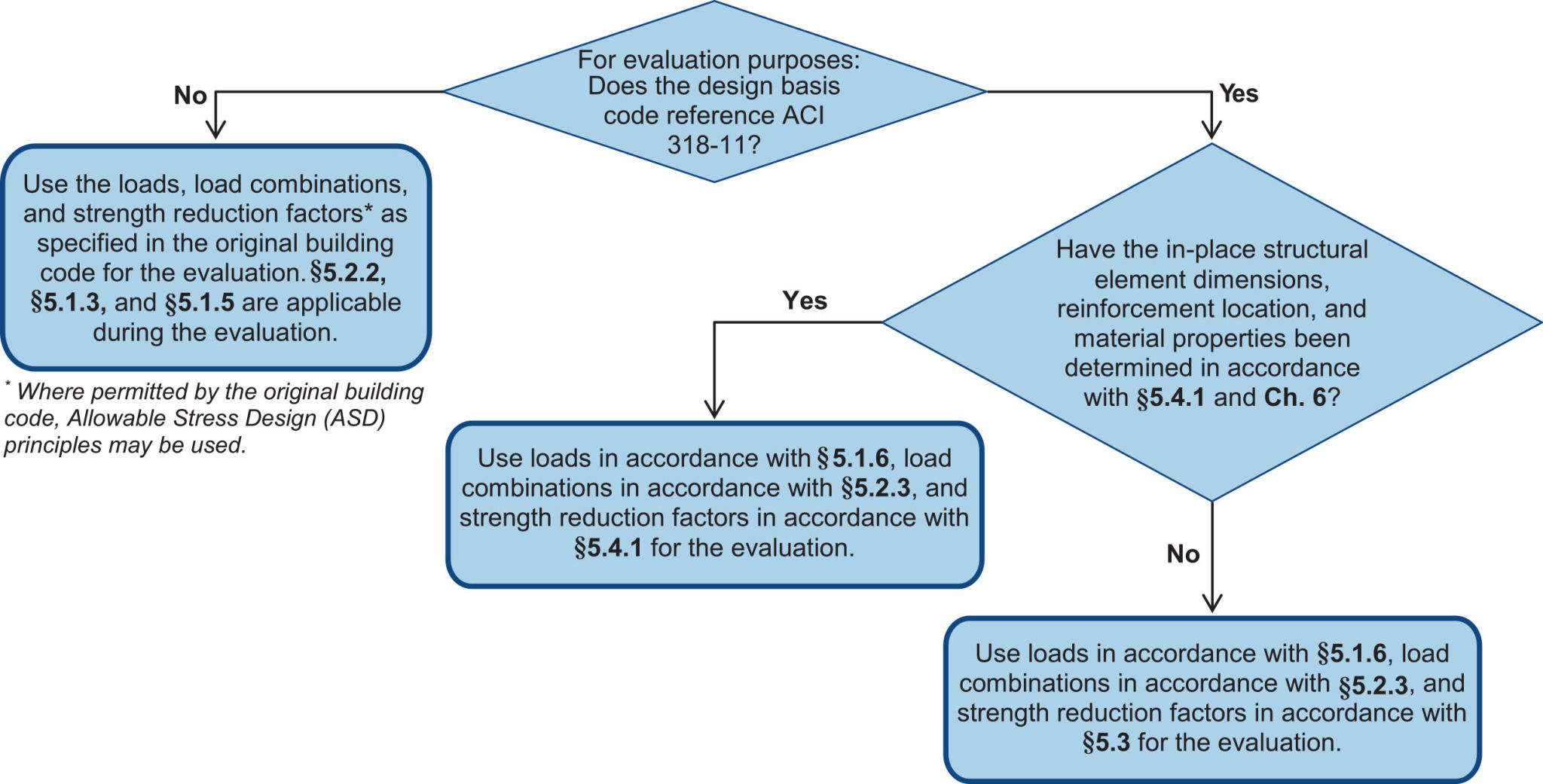

For example, Chapter 5 of ACI 562 addresses licensed design professionals’ (LDPs’) responsibilities for determining loads and strength reduction factors for elements being repaired, as well as the entire structure. The evaluation of existing buildings differs from designing new ones. In-place materials, as-built geometries, and material properties can be investigated, reducing the uncertainty of these properties. Strength reduction factors used from new design (such as ACI 318) may be unnecessarily conservative with these reduced uncertainties.

Codes for new construction, such as ACI 318, must conservatively estimate the strength of a structure that is yet to be built based on several parameters that can vary between the specified values and the actual values in the finished structure. For existing structures, the variability of these parameters can be reduced by testing and measurements made on the actual structure in the field. ACI 562 encourages the designer to verify these values in the field by allowing them to use a less conservative strength estimate that reflects this reduced variability. (For more details on the basis of ACI 562, and areas where it differs from ACI 318, see the ACI/ICRI video presentation, “Introduction to the Concrete Repair Code [ACI 562],” which is available online at bit.ly/1Ugbyd6[1]).

ACI 562 walks users through the process of selecting a design basis code (i.e. the project’s original building code or current code that applies in the particular jurisdiction, such as the 2012 IBC) to ensure a minimum level of safety regarding load and strength requirements. If a design-based code requires the use of ACI 318 for the evaluation or repair design, then the new construction provisions in ACI 562 for load factors, load combinations, and strength reduction factors should be used instead of the original building code (Chapter 5.1).

An engineer may decide to use load factors and load combinations from the structure’s original building code, as long as they meet the proper safety requirements of that code. Provisions for strength reduction factors from ACI 562 cannot be used in combination with load factors and load combinations from the original building code.

While providing minimum design requirements such as these, ACI 562 effectively accommodates the varied and unique strategies and materials designers can use.

2. A repair-specific code saves money.

As ACI 562 does not require the repair and rehabilitation design to meet building codes for new construction, the designer can devise applicable, and often more economical, repair solutions. Techniques and materials can be tailored to the structure’s unique and specific needs, considering factors such as age, original materials used, and environmental conditions.

ACI 562 has also been referenced in expert reports for litigation cases, resulting in significantly reduced financial settlements. Denver-based J.R. Harris & Company (JRH) recently used it in several litigation reports assessing damages in existing concrete structures.

As an approved consensus standard (i.e. according to American National Standards Institute [ANSI] procedures), ACI 562-13 has been accepted as the source standard to use for damage assessment and repair design on individual projects by Greenwood Village and Pikes Peak Regional Building Departments in Colorado. In these instances, JRH was able to cite ACI 562 in its recommendation for structural remediation and determination of damages.

Chapter 4 of ACI 562 describes the compliance method to use in a repair project. In general,

the ‘original’ building code is used for minor alterations—the ‘current’ building code (e.g. 2012 IEBC or IBC) serves as the design basis for major alterations or significant load changes, while the ‘existing’ building code (e.g. 2012 IBC) applies to evaluation and design of rehabilitation of seismic damage. Unless structurally unsafe, deterioration or faulty construction in an existing building will not require modifications to satisfy the current building code.

By applying the lesser of the demand-to-capacity ratio required by the original building code or the current building code (if upgrades to the current building code are not required by the jurisdiction), the costs to correct faulty construction can be lower than if they are set strictly by current building code requirements. In one case involving rehabilitation work on four buildings with faulty construction, JRH was able to reduce the repair costs from $12 million to $3 million, with a repair plan based on the lesser of the demand-capacity ratio based on either the original or current building code per ACI 562.

3. Stakeholder responsibilities are clarified.

For the first time, ACI 562 clearly establishes the responsibilities of owners, designers, and contractors involved in concrete repair. For example, Chapter 9 summarizes specific roles and responsibilities for three considerations often encountered in repair projects:

- stability and temporary shoring;

- temporary conditions; and

- environmental issues.

According to ACI 562, a licensed design professional must include requirements for stability and temporary shoring in a repair project. The shoring engineer (typically a third party hired by the contractor) follows ACI 562 provisions to design shoring and bracing. The contractor is responsible for determining the means and methods of executing the repair process.

Once repairs are underway, the contractor should notify the licensed design professional to observe the deterioration, faulty construction, or damage during construction to determine whether it is more severe or different than anticipated. The designer can then determine what measures are necessary to maintain structural integrity while repairs are implemented.

When designers, contractors, owners, and building officials are working from the same code, the entire project team has the same expectations regarding the design and execution of concrete repairs.

4. Building officials now have a tool for evaluating rehabilitation design.

Before ACI 562, rehabilitation of existing structures was sometimes held to unrealistic standards. Without a repair-specific code, building inspectors referred to codes intended for new construction, such as ACI 318. This often resulted in unnecessarily extensive or costly repairs. By establishing minimum life safety requirements for rehabilitated structures, the newer ACI code is designed to help preserve existing structures that would otherwise be neglected or demolished.

ACI 562 requires inspection and testing of concrete repairs to meet the minimum inspection requirements of the existing building code or local jurisdiction. The LDP must specify these requirements within construction documents, as well as supplemental inspections and tests appropriate to the project (Chapter 10.1.1).

To facilitate construction observations, the LDP must specify that existing conditions and reinforcement cannot be concealed with construction materials before the work is inspected. However, the code allows the designer to determine (on some projects)

that only representative repair locations need to be inspected.

5. Several resources can help specifiers implement the code.

To help concrete professionals interpret the new code’s requirements, ACI and ICRI have collaborated to create the Guide to the Code Requirements for Evaluation, Repair, and Rehabilitation of Concrete Buildings. (The guide is available in print and digital formats through at www.icri.org[2] and www.concrete.org[3]). The reference expands the users’ knowledge base and provides options for designers to use their professional judgement in determining how to provide better repair solutions.

‘Chapter guides’ summarize each chapter of ACI 562 and provide insights into how each of these chapters of the code applies to different aspects of concrete repair, including:

- basis for compliance;

- evaluation and analysis;

- design of structural repairs;

- durability; and

- construction.

Flowcharts such as the one in Figure 1 illustrate key decision-making points in the process, and call-out boxes—such as “Is a Structural Evaluation Always Required?”—provide additional analysis, commentary, and references not explicitly covered by the code.

The guide uses real-world project examples to show how ACI 562 requirements apply to common repair scenarios, including:

- typical parking garage repairs;

- typical façade repairs;

- repair of historic structure for adaptive reuse;

- strengthening of two-way flat slab; and

- strengthening of double-tee stems for shear.

Project descriptions include photos and design details, as well as references to ACI 562 provisions that correspond to each phase of work, from evaluation through design and construction. Rather than providing a ‘how-to’ manual, these examples illustrate ways in which designers can apply the code to fit unique repair scenarios.

Licensed design professionals, owners, and contractors can learn more about ACI 562 through the institute’s educational sessions where engineers (including this article’s authors) present case studies to explain the repair design provisions and their applicability to quality assurance (QA), structural repairs, and external reinforcing systems. (For example, the ACI Spring Convention takes place in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, April 17−21. Committee E702 will host an educational session, entitled “Applicability and Use of ACI 562 Concrete Repair Code.” Visit www.concrete.org/events/conventions.aspx[4]). Further, members of the ACI Committee 562—many of whom are consulting engineers with experience in the code’s intricacies—are also available to assist with questions on an ongoing basis.

Conclusion

As a standard, ACI 562-13 represents the current structural engineering state of the art for evaluation and repair of existing concrete structures. It has evolved as the source for standard of care, or the quality of work expected of design professionals, in assessing existing concrete structures.

By understanding ACI 562, engineers and architects can improve the overall quality of concrete repairs while realizing significant benefits for contractors and owners. These knowledgeable concrete professionals can also educate project owners and municipalities about the new repair requirements that are becoming standard practice.

Building officials have already begun approving the use of ACI 562 on a case-by-case basis, and local jurisdictions can adopt the code directly. ACI 562 is also compatible with the International Existing Building Code (IEBC), and may be adopted as part of IEBC 2018.

| IS A STRUCTURAL EVALUATION ALWAYS REQUIRED? |

|

Through a series of highlighted call-out boxes, the Guide to the Code Requirements for Evaluation, Repair, and Rehabilitation of Concrete Buildings provides further explanation and references related to the provisions of American Concrete Institute (ACI) 562, Code Requirements for Evaluation, Repair, and Rehabilitation of Concrete Buildings. The following is an excerpt from a call-out box addressing structural evaluations: ACI 562 does not require the licensed design professional (LDP) to perform a detailed structural evaluation in cases where the capacity of the structure is known. Consider the following scenarios when a structural evaluation would not be required. Scenario #1: A beam at the lower level of a shopping center is impacted by an errant vehicle. The plans and available documents were reviewed as part of the preliminary evaluation and indicate the beam was designed to satisfy the required loading. Based on the LDP’s preliminary evaluation, the damage is limited to cracking and spalling of the concrete cover at a single beam location. There are no visible signs of damage to the existing reinforcement. Based on these results, the LDP may proceed with the design of the repair without performing a more detailed structural assessment or structural analysis of the existing beam or structure. Scenario #2: An LDP is retained to review the in-place condition of a parking garage and provide documents for repairs or maintenance. During the preliminary evaluation, the LDP learns the manager has recently started using de-icing salts on the ramps and parking areas. In addition to replacing failed sealant joints and performing other routine maintenance, the LDP is considering a coating or sealer for durability considerations of the salt-exposed deck. The preliminary evaluation performed by the LDP indicates the garage is in otherwise good structural condition with no signs of deterioration or structural deficiency. The LDP may proceed with the coating system design and durability repairs without performing a structural assessment or structural analysis of the existing deck or garage. In this instance, additional assessment (for example, material sampling to determine chloride levels in the deck) is not required based on ACI 562, Chapters 6.1.2 and 6.1.3. A chain drag survey of the deck might be considered prior to performing coating repairs. |

Jay H. Paul, SE, FACI, is a senior principal of Klein and Hoffman in Chicago, and has served the industry through numerous professional organizations including being past-president of the Structural Engineers Association of Illinois (SEAOI) and a past-chair of the American Concrete Institute (ACI) Committee 546 on concrete repair. Paul is currently a member of the International Concrete Repair Institute (ICRI) and ACI Committee 562 on evaluation, repair, and rehabilitation of concrete buildings. Recently, he chaired the review committee for the development of the Guide to the Code for Evaluation, Repair, and Rehabilitation of Concrete Buildings. He can be contacted at jayhpaul@comcast.net[5].

Gene R. Stevens, PE, SE, M. ASCE, is the chair of ACI 562, Subcommittee A and of the Structural Engineers Association of Colorado’s (SEAC’s) Existing Structures Committee. A principal with J. R. Harris & Company in Denver, Colorado, his focus includes the behavior and performance of members, systems, and structures, along with the investigation, evaluation, and assessment of existing concrete and wood buildings, and the design of repairs and rehabilitations for faulty construction, damage, and deterioration in existing structures. Stevens may be reached at gene.stevens@jrharrisandco.com[6].

- bit.ly/1Ugbyd6: http://bit.ly/1Ugbyd6

- www.icri.org: http://www.icri.org

- www.concrete.org: http://www.concrete.org

- www.concrete.org/events/conventions.aspx: http://www.concrete.org/events/conventions.aspx

- jayhpaul@comcast.net: mailto:jayhpaul@comcast.net

- gene.stevens@jrharrisandco.com: mailto:gene.stevens@jrharrisandco.com

Source URL: https://www.constructionspecifier.com/taking-a-new-approach-to-concrete/