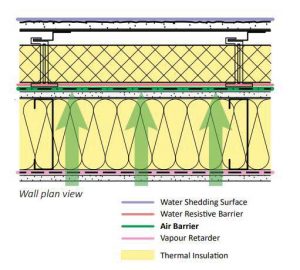

Diffusion rates through wall assemblies have been shown to be generally slow. All things being equal, breaches in the vapor barrier result in significantly lower quantities of moisture migration as a result of diffusion rather than the quantity of moisture transported through the same material due to air movement. As such—despite what many often assume—vapor barriers need not be continuous in wall assemblies, and may, at times, (depending on climate) be omitted altogether.

Different meanings

The importance of effective communication in the construction industry cannot be overstated. However, barriers (no pun intended) exist that can impede or distort effective communication and result in failure or undesirable effects. Amongst these barriers, the use of jargon is often cited as a leading cause of communication breakdown. Specifically, in the construction industry—due to its fragmented structure, technical nature, and the adversarial tendencies of its stakeholders—the lack of terminology standardization has engendered different terms and meanings that are understood differently across actors. Figure 2 illustrates how misunderstandings can occur between two professionals interpreting technical jargon differently. Unfortunately, these complex and ambiguous terms, often well-understood by discrete groups, but prone to misinterpretation by others, plague the industry.

Photo © BigStockPhoto.com

The term ‘air/vapor barrier’ is an example of such ambiguous terminology. The ambiguity of this term is inherent in its use of the slash ( / ) punctuation mark. In English, the slash can be used to either denote ‘or’ or ‘and.’ Therefore, in theory, the term ‘air/vapor barrier’ can be interpreted as ‘air or vapor barrier’ or ‘air and vapor barrier.’ In general contexts, however, it is safe to assume most people use it to refer to the latter. Yet, as it has been discussed previously, the term ‘vapor barrier’ is itself a subset of the term ‘vapor retarder’ (i.e. only a Class I vapor retarder is considered a vapor barrier). Should the term ‘air/vapor barrier’ then be restricted to materials meeting the requirements for air barrier materials and Class I vapor retarders? The advent of materials having various levels of permeability (e.g. spun-bonded polyolefin, silicone, and vapor permeable polyurethane foam) clearly show such a restriction would prove overly exclusive.

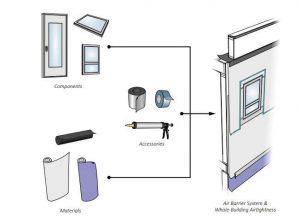

Any alternative to ‘air/vapor barrier’ should reduce ambiguity while reflecting the current trends of the industry. At present, we understand the benefits of controlling air leakage clearly outweigh the control of vapor diffusion. Therefore, ‘air/vapor barrier’ should be replaced with a term describing an air barrier material, which also has some vapor-retarding characteristics. As the permeability of materials has already been standardized in building codes, it is perhaps most appropriate to borrow this terminology and apply it to the problem under discussion. See Figure 3 for a proposed system with four distinct designations and associated properties.

Image courtesy J. Lstiburek

Conclusion

It is no secret the construction industry is plagued by a chronic productivity problem. A 2015 report by McKinsey & Company showed that while productivity rates in the manufacturing sector nearly doubled over the 20-year period spanning from 1995 to 2015, productivity rates remained painfully flat, or even worsened, in the construction industry. Factors such as the fragmented structure of the industry, the cyclical nature of construction activities, and poor or inadequate communication have all been suggested as contributors to this lack of productivity growth. Moreover, these sluggish gains may also be reflective of the industry’s unwillingness to embrace change.

The future is, however, not all bleak. Recent years have shown consultants and contractors alike embrace new technologies such as building information modeling (BIM), drones, and prefabrication to increase output and reduce errors. Accordingly, the language used in construction today must express and reflect the current state of affairs. Terms and materials no longer serving their purpose should be retired and replaced with new ones illustrating advancements in research and practice.

Thus, the term ‘air/vapor barrier’ should be replaced by ones illustrating both the air leakage and vapor permeance properties of these materials. Ultimately, the biggest challenge to any term proposed will be to overcome the inertia forces associated with the construction industry’s fear of change.

The opinions expressed in Specifications are based on the author’s experiences and do not necessarily reflect those of The Construction Specifier or CSI.

Juste Fanou is the director of Jm|F Technical Documentation Solutions Inc. He is a bilingual technical documentation specialist and specifications writer with more than 10 years of experience. Fanou has assisted multiple clients in the development of front-end and technical specifications including the evaluation of material substitution proposals, and the interpretation of standards. He holds a certificate in building science, a diploma in architectural technology, and a degree in civil engineering technology. Fanou can be reached at jfanou@jmfservices.net.

No doubt, improper use of terminology can be a big problem in communication about construction detailing, just as it can be about other aspects of our industry such as BIM and general computer-related issues. As a senior architect, I strive to use and educate others on the proper terms to address what we are implementing and what we are learning about. In this case, I do take issue with the chart that compared architects’ understanding of some of those terms to engineers’ as I would like to think our profession is on a little higher level of knowledge than what that figure implies. Thank you very much for this good contribution to the discussion!

There are still some controversy about the location of the water resistive barrier (WRB) in an exterior wall assembly when a continuous insulation (ci) is used. There are some wall systems that suggest the installation of the WRB behind the (ci) and over the exterior sheathing. In the other hand other exterior (ci) wall systems included an integral aluminum foil at the interior and exterior faces of the (ci) using the exterior face as both, WRB and air barriers, when the seams and penetrations through the (ci) are properly sealed. The exterior aluminum foil face become the drainage plane of the wall assembly. This wall assembly in many instances does not even require installation of any exterior sheathing. The only other topic that requires attention is the exterior wall dew point calculations to determine if a vapor barrier is required or not and where is the correct location. Agreed, terminology may create issues, but in many cases all different approaches to install (ci) make this topic even more complex.

Thank you very much for this detailed content on air and vapor barrier. A useful and great content, your blogs are always great and I love reading them. This is a really informative article to share. Keep posting more. Well, I have visited another site moisturebarrier.co.nz having some wonderful and similar information.