The Emergence of Thin Brick: Understanding adhered veneer

Design issues

Another important topic is the water penetration resistance of thin-brick veneer assemblies. Adhered veneer systems are considered barrier walls since there typically is no drainage space. Therefore, the drainage plane, where moisture penetration is stopped, is the water-resistive barrier (WRB).

The WRB is typically the traditional No. 15 building felt. One layer is used on interior applications, but two layers are required for exterior applications. One layer of No. 30 felt can be used in place of two No. 15 layers. As the water-resistant barrier is often used as the primary drainage plane, it must be durable and free from holes.

The code-required WRB is there to resist liquid moisture trying to make its way through the wall system—it is not meant to prevent air movement or any moisture piggybacking its way through the wall system. That role belongs to the air barrier, which is a continuous membrane or coating used to stop air transfer through the wall.

Some substrates can act as an air barrier as with a concrete backing, but an applied air barrier material is typically used. They would be placed directly on the backing before the thin brick system. Adhered thin-brick veneers can be installed directly onto the air barrier using polymer mortars, but may not perform as well when a traditional mortar is used to adhere thin brick to the wall. While not specifically addressed by the code, an air barrier may perform water-resistive functions, rendering a separate WRB unnecessary.

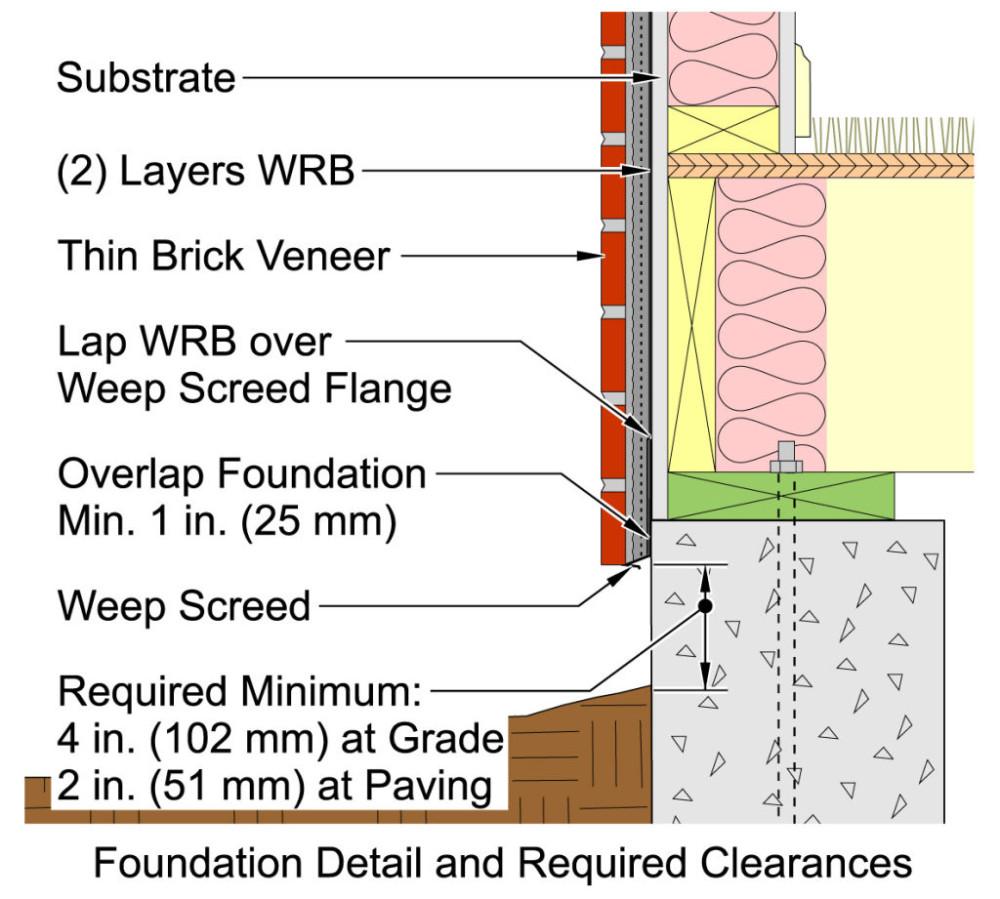

While this is a barrier wall, flashing is still necessary, but only at window heads and sills and under the first course of masonry. A foundation detail is shown in Figure 3**. To enhance the water penetration resistance of this wall system, drainage mats have been installed to the exterior of the moisture barrier to capture any water that does penetrate; however, these tend to be proprietary systems.

Recent energy codes are requiring more insulation. Placing insulation within a thin-brick system can be challenging. Rigid insulation can be a part of the panel system itself where the brick is placed into grooves in the panel. Insulative sheathing can be used between the studs and the veneer system or it can be rigid board insulation behind the panel. Batt insulation can be placed within the stud cavity of backing, but that does not provide for continuous insulation (ci), which may be a requirement in some codes. Insulation can be placed within the precast concrete panel or the masonry backing if appropriate.

Movement joints must be used in thin brick as in other brick wall systems. For full-brick veneer walls, the recommendation is usually about every 7.6 m (25 ft), but for thin-brick veneer it is recommended the movement joints be spaced closer together. Part of this is due to the differential movement between the thin brick and its mortar or concrete backing. Further, because this is a more flexible system, placing the movement joints closer together limits deflections and possible cracks from occurring. The Brick Industry Association (BIA) recommends expansion joints be placed approximately every 5.5 m (18 ft) apart to be conservative. When using a mortar bed and metal lath, the joint should run through the entire system.

Material specifications

Thin brick comes in most of the same colors and textures as full brick so there are a lot of choices. It also comes in different shapes to complement the stretcher brick. In most cases, a corner brick will be required so mitered joints do not have to be used. The face size of the thin brick can also match full sizes, so whether a modular size or utility size is needed, the brick manufacturer should be able to match it.

There are two basic ways of making thin brick. The first is for the manufacturer to develop a way to extrude the brick and then cut or break the unit into its correct size and shape. In some cases, a manufacturer makes a type of hollow brick where the webs can be broken away from the face, resulting in two thin brick pieces. This may limit some of the sizes and textures of the brick depending on the manufacturer. Brick manufactured in this way can also have dovetail slots on the backs.

In other cases, a brick manufacturer just cuts the face off a full-size or soap brick. This is done to provide the same wide range of colors and textures they offer. Various saws are used, from simple to complex automated systems. Any scrap from the cutting is returned to the manufacturing process. Thin brick produced in this manner will have a smooth surface on the back.