The Leap-frog Effect: Protecting tall buildings from exterior fire spread

by Tony Crimi, P.Eng., MASc.

Fires can spread through buildings even without the involvement of the cladding system materials. There are numerous examples of fire spread from the room of origin to the space above via vertically adjacent windows, but prior to the Grenfell Tower fire in the United Kingdom, most have caused only property damage. A majority of deaths or injuries on floors other than the fire-origin floor were a result of smoke. However, some methods of insulating buildings to improve their sustainability and energy efficiency are changing the external surfaces of structures. this has resulted in an increase in the volume of potentially combustible materials.

Additionally, different construction techniques favoring energy performance are being utilized. As recent high-rise fires around the world have demonstrated, it is critical designers remain vigilant against potential fire hazards, particularly as the industry transitions to tighter and more energy-efficient buildings, and adapts traditional perceptions to these new methods of construction.

The intersection of the exterior wall and the floor assembly provides a number of different paths for vertical fire spread in buildings. Each of these paths is addressed by different test standards. The building codes establish different requirements for each of these potential paths to prevent the spread of fire. The intent is to confine a fire to the room of origin and prevent propagation to adjacent areas.

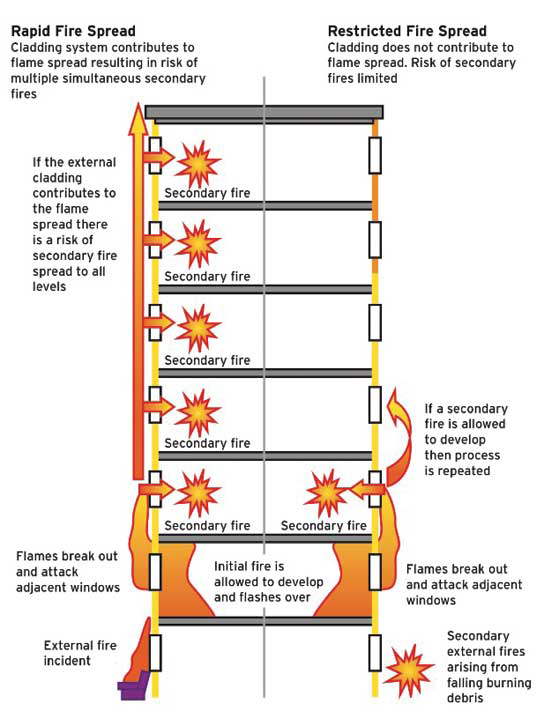

Fire spread

Real fire experience has taught the author ineffective curtain wall design, perimeter void fire protection, or inadequate spandrel protection can allow fire to spread through the space between floors and walls, the window head transom, and the cavity of the curtain wall. This can occur either by ignition of the exterior building cladding materials, through window glass breakage, or around melted aluminum spandrel panels. Conceptually, fire can easily spread to adjacent floor levels at the exterior wall via three paths (Figure 1).

Image courtesy Tony Crimi

Through voids

Fire can spread within the building through the void space created between the edge of the floor and an exterior curtain wall. These are protected by perimeter fire barrier systems. Standards to assist in the proper design and installation of fire barrier systems include ASTM E2307, Standard Test Method for Determining Fire Resistance of Perimeter Fire Barriers Using Intermediate-scale, Multistory Test Apparatus, for system design specification, and ASTM E2393, Standard Practice for On-site Inspection of Installed Fire Resistive Joint Systems and Perimeter Fire Barriers, for proper installation.

Through cavity

Fire can also spread through a void or cavity within the exterior curtain wall. In this situation, fire would spread by a path within the concealed space of the exterior wall, or along the outer surface of the exterior wall. According to some jurisdictions, these protected assemblies are tested to be compliant with the National Fire Protection Association (NFPA) 285, Standard Fire Test Method for Evaluation of Fire Propagation Characteristics of Exterior Non-loadbearing Wall Assemblies Containing Combustible Components, which evaluate flame propagation due to combustible materials used in exterior wall assemblies.

Leap frog

This is a window-to-window mechanism where combustible materials behind an upper window are ignited as a result of the intense heat from flames projected out of a lower window. This mechanism is currently addressed in the U.S. building codes prescriptively, using spandrel panels or sprinkler protection. A new ASTM test method is under development. This condition represents a significant fire exposure, created when the magnitude of flame and hot gasses escaping through a window opening is sufficient to cause the re-entry of the fire or ignite combustible materials, in the room above the story of fire origin. This can occur when fire spreads vertically up the exterior of the building, circumventing the interior perimeter fire barrier joint system, any inherent fire resistance of the exterior wall assembly, or a sprinkler system. When this mechanism of fire spread occurs at a given floor, it has the potential to repeat through the same mechanism to every floor above it. Therefore, this phenomenon is referred to as the “leap-frog” effect.

Flame extension and heat fluxes to the window areas above an opening can be expected to be greater where combustible claddings are employed in lieu of traditional code-prescribed fire-resistive spandrel panels. The design characteristics of a spandrel panel and the perimeter fire barrier joint system are important to enhance the ability of the exterior wall to protect against vertical fire spread. Fire tests such as ASTM E2307 have shown typical aluminum-framed curtain walls require glass installed in the spandrel area immediately above openings be appropriately protected. Additionally, this testing has demonstrated the aluminum mullions also require insulation protection to support the perimeter fire barrier joint system. Otherwise, the frame can melt, soften, or distort, and cannot support the perimeter joint protection or spandrel wall system. These measures help keep the glass spandrel panel, and any associated fire barrier joint system, intact.