The new slip resistance requirements in IBC

Sustainable slip resistance

A major international fast-food chain found that in some cases where slip-resistant flooring was installed in a busy restaurant, wear from many thousands of shoes (and the soil on them) could destroy the wet slip resistance in a few weeks or months. This company spent years devising a test to indicate whether a flooring sample was likely to give good slip resistance after years of heavy wear.

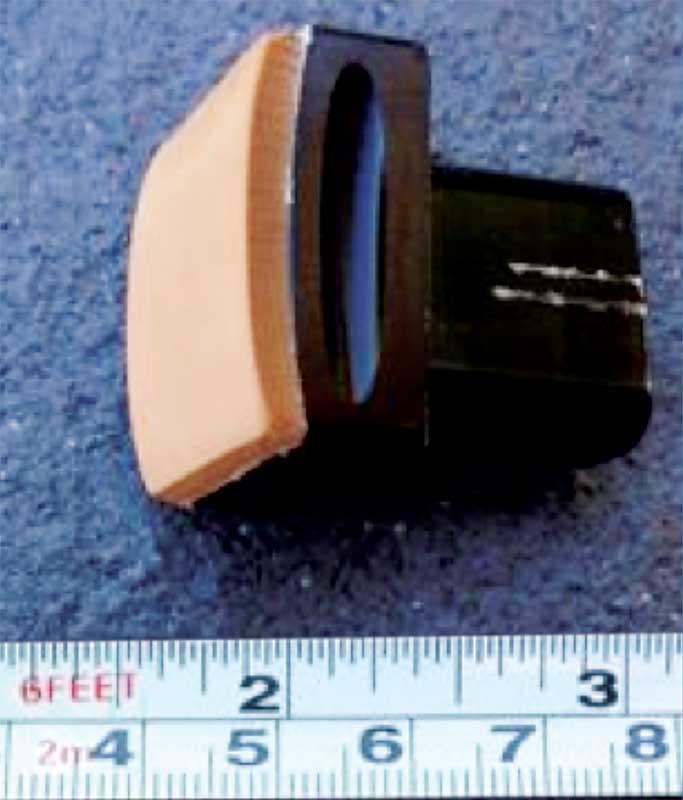

The test involves measuring the wet PTV of the sample when new, then subjecting it to a standard abrasion, then testing the wet PTV after abrasion. (For more, see C.J. Strautins’ papers, “Sustainable Slip Resistance: An Opportunity for Innovation,” presented at the Spanish conference, Qualicer in 2008 and “Enhanced Test Method for Assessing Sustainable Slip Resistance,” at the 2007 International Conference on Slips, Trips, and Falls). The specification is the wet PTV must be 35 or higher after 500 cycles of abrasion using a standard abrasive pad loaded with 1 kg (2.2 lb). When the sample meets this, it is said to have “Sustainable Slip Resistance.” Other large property owners, including two major cruise ship companies, are now having their candidate flooring samples tested for this Sustainable Slip Resistance.

Barefoot flooring

Another test worth noting was devised in Germany and adopted in modified form in Australia as AS/NZS 4586:2004, Slip Resistance Classification of New Pedestrian Surface Materials, Appendix C, “Wet/barefoot ramp test method.” This involves two technicians individually walking a wet 1-m (3-ft) long flooring sample in bare feet on a variable-angle ramp. The technician adjusts the ramp angle so he or she just barely can walk without slipping. Depending on the angle, the sample is classified as A, B, or C, with C having the greatest wet slip resistance. The A category is suitable, for instance, for locker rooms, while B is for swimming pool decks and C is for swimming pool ramps and steps leading into the water.

While the test is the most realistic one for barefoot situations, it is still a laboratory test and is impractical for checking quality of flooring after it has been delivered to the jobsite—or already installed. For onsite testing, the pendulum with a soft rubber slider is the preferred method of testing barefoot flooring.

A similar variable-angle test is used to rate flooring for industrial-type shoes having treads in oily situations, and is a standard in Germany and in Australia as the aforementioned AS/NZS 4586:2004 Appendices C and D (“Oil-wet Ramp Test Method”). However, the results are not applicable to general commercial situations where most pedestrians are not wearing shoes with effective treads.

When to test flooring

It is commonly assumed when a flooring sample is tested once, for instance for a catalog DCOF, that its slip resistance will always be the same. This has led to some expensive and embarrassing mistakes.

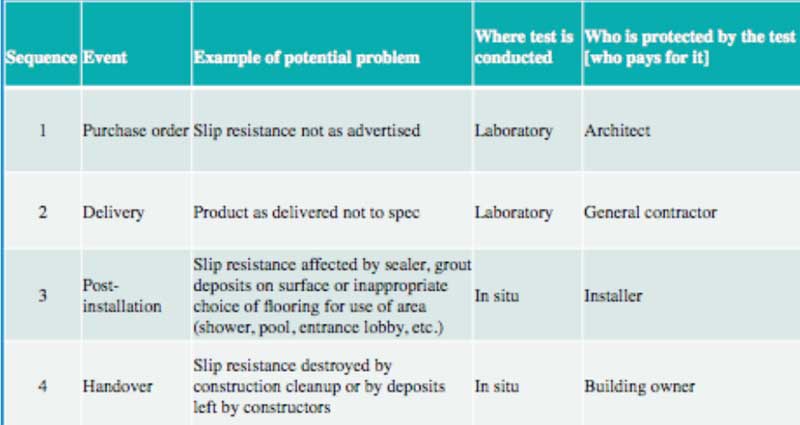

For a large project, experience has shown the flooring needs to be tested at four stages to protect the various parties involved:

- the architect or specifier;

- the general contractor;

- the installer; and

- the building owner.

The party being protected should normally be the one who pays for the test. Figure 1 shows when tests should be done and who should pay.